A Tale of Two Cities:

A Trip to the Silicon Valley

Between 1927 and 1934, the German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin undertook several experiments with mind-altering drugs, like mescaline, opium, and hashish. Benjamin kept records of these experiments in the form of protocols, an “enumeration of impressions,” the aptly titled “Hashish in Marseilles” being one of them. In true flaneur fashion, Benjamin ate some hashish during a hot summer night in Marseille, ventured out to take it all in, and wrote down what he saw, felt, and thought. For Benjamin, the drug experiences opened doorways to aesthetic and philosophical recognitions. At a time when the situation surrounding drugs was changing rapidly and new regulations continuously contained their circulation, Benjamin aspired to gain individual knowledge in his self-attempts. One thought he formulated on this Marseille trip was the history-traversing statement “from century to century, things grow more estranged,” which introduces this following aesthetic and philosophical survey of the state of psychedelics in the current century.

Almost a hundred years after Walter Benjamin’s adventures in the South of France, the situation surrounding drugs is again changing rapidly and new regulations continuously expand—as opposed to contain—their circulation. What, exactly, happened in the decades in between for this type of normalization to occur? How estranged it indeed seems to read Benjamin’s elaborations on drugs now—treating the experience as terra incognita—at a time where cannabis, opioids, and psychedelics comfortably find their positions in mainstream culture.

Walter Benjamin on hashish

Initial clues on what might have happened can be found during the countercultural decades of the 1960s and 1970s, 40 years after Benjamin’s stint in Marseille: during that time, drug culture became a signifier of those positioned against the establishment, a way of showing association by deviation. Regarding this positioning, the sociologist Jock Young made the following statement in 1972 in Oz, a magazine associated with the British underground press: “Normalization is a major form of social control. It involves the swallowing up of deviant forms and practices and incorporations of them in a fashion that is supportive of the status quo and a rejection of anything that posed as a challenge to the system.”

Oz, at the time, was concerned with countercultural topics such as anarchism, queerness (which was not called that just yet), the critique of institutionalized violence through police and state, and drugs. It was in relation to the latter that Young continues: “Drugs contain within them no essence, their efforts, their effects are the reflection of the culture which imbibes them.” The drug culture of Walter Benjamin’s 1920s and 1930s was one of clandestine discovery and lofty thought experiments—not mainstream, but also not bothered too much by being in its vicinity. The years of regulation and control that followed gave way to the drug culture of the ’60s and ’70s, which positioned itself at the fringes of society, firmly opposed to the wary, prohibition-inflicted opinion of all mind-altering substances that dominated at the time.

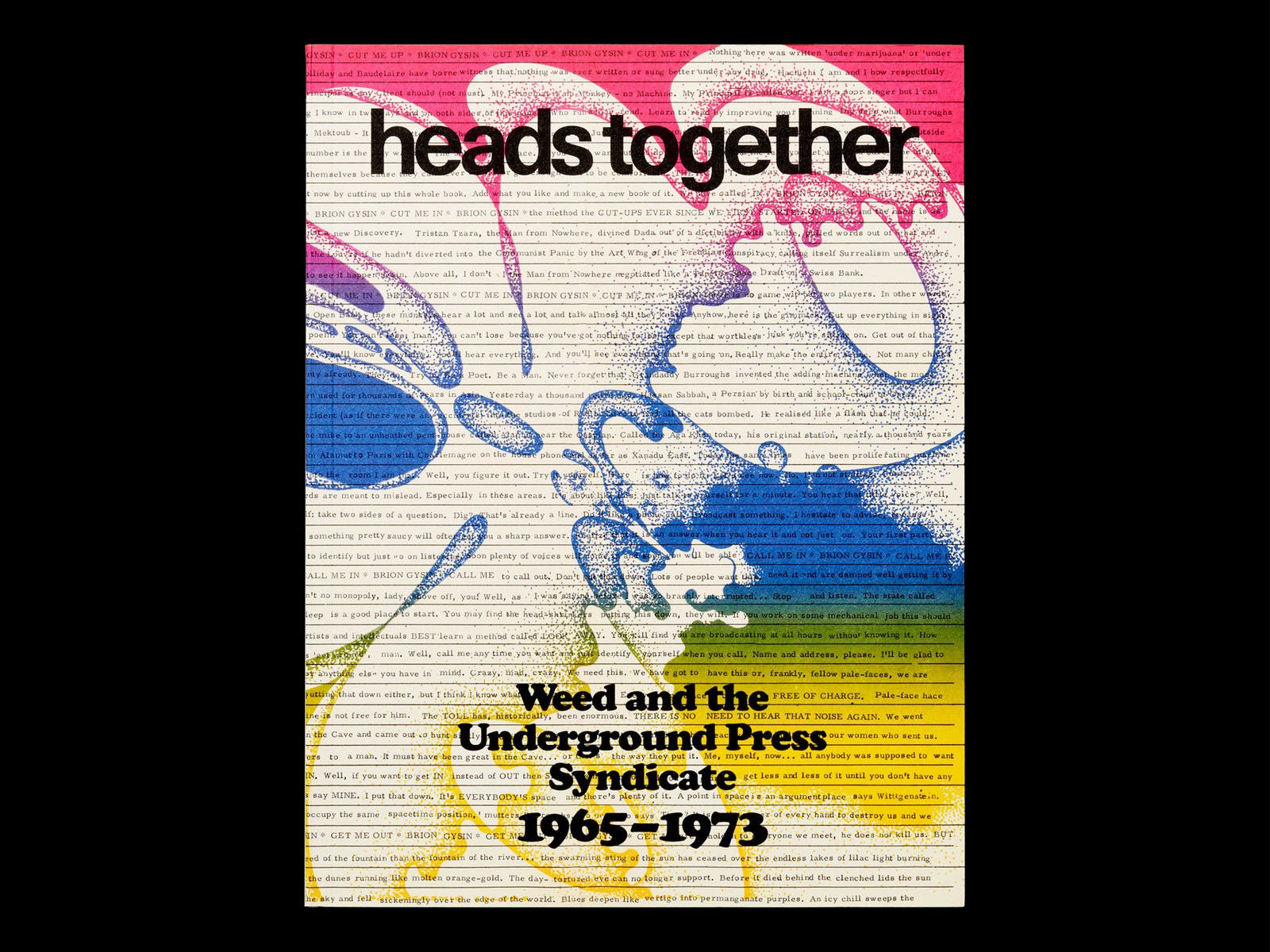

Heads Together: Weed and the Underground Press Syndicate, 1965-1973, Edited by David Jacob Kramer(2023)

I lifted the quote by Jock Young from Heads Together. Weed and the Underground Press Syndicate, 1965–1973 edited by David Jacob Kramer and recently published by Edition Patrick Frey. In the book, Kramer and others tell a (visual and oral) history of the Underground Press Syndicate, a confederation of different fanzines and papers in the United States and, consequently, the world, in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The book’s title hints at its object of inquiry: it collects material of the stoner-art canon, countercultural ephemera that in its abundant, dilettantish, and maximalist aesthetic paints the picture of a bygone era. Today, recreational drugs are at the brink of legalization—cannabis has become a multi-billion-dollar industry in the United States over the last few years—and what was once firmly embedded in countercultural ideas has since been swallowed up by the “system,” per Young. His prediction became truer than he probably would have ever imagined.

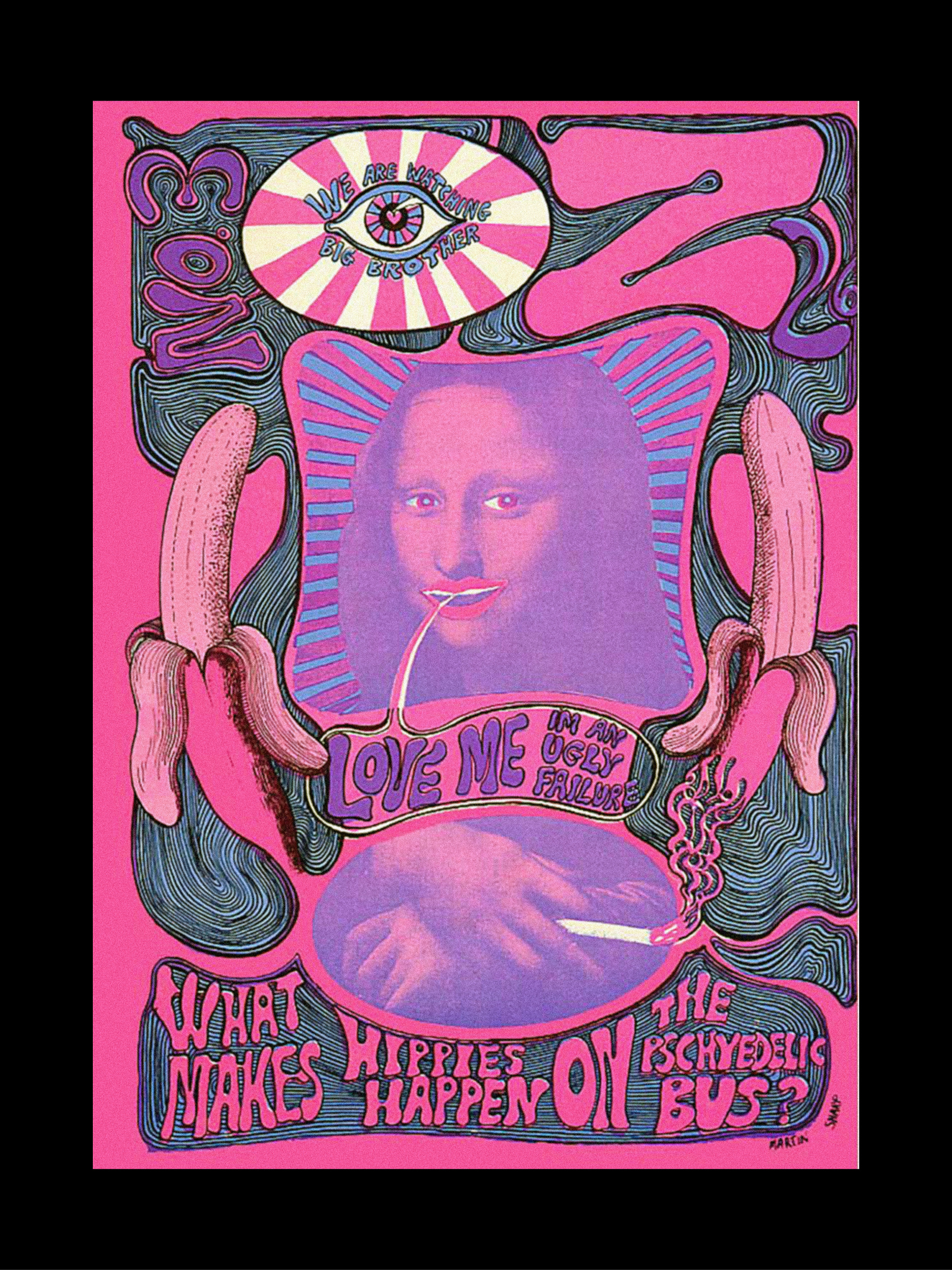

OZ Magazine No 3. (1967)

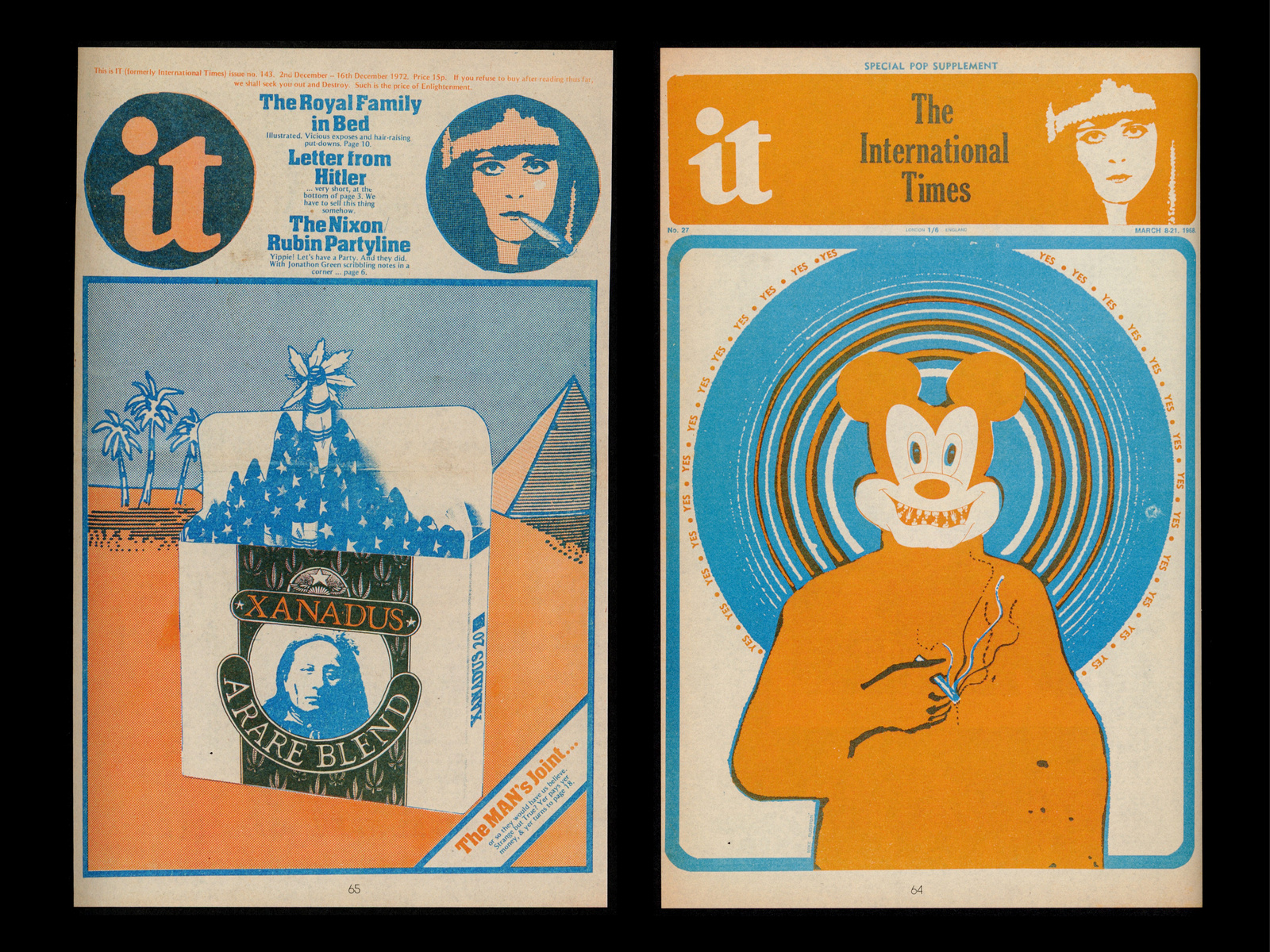

Left: Good Times (1971) / Right: it (formerly The International Times) (1968)

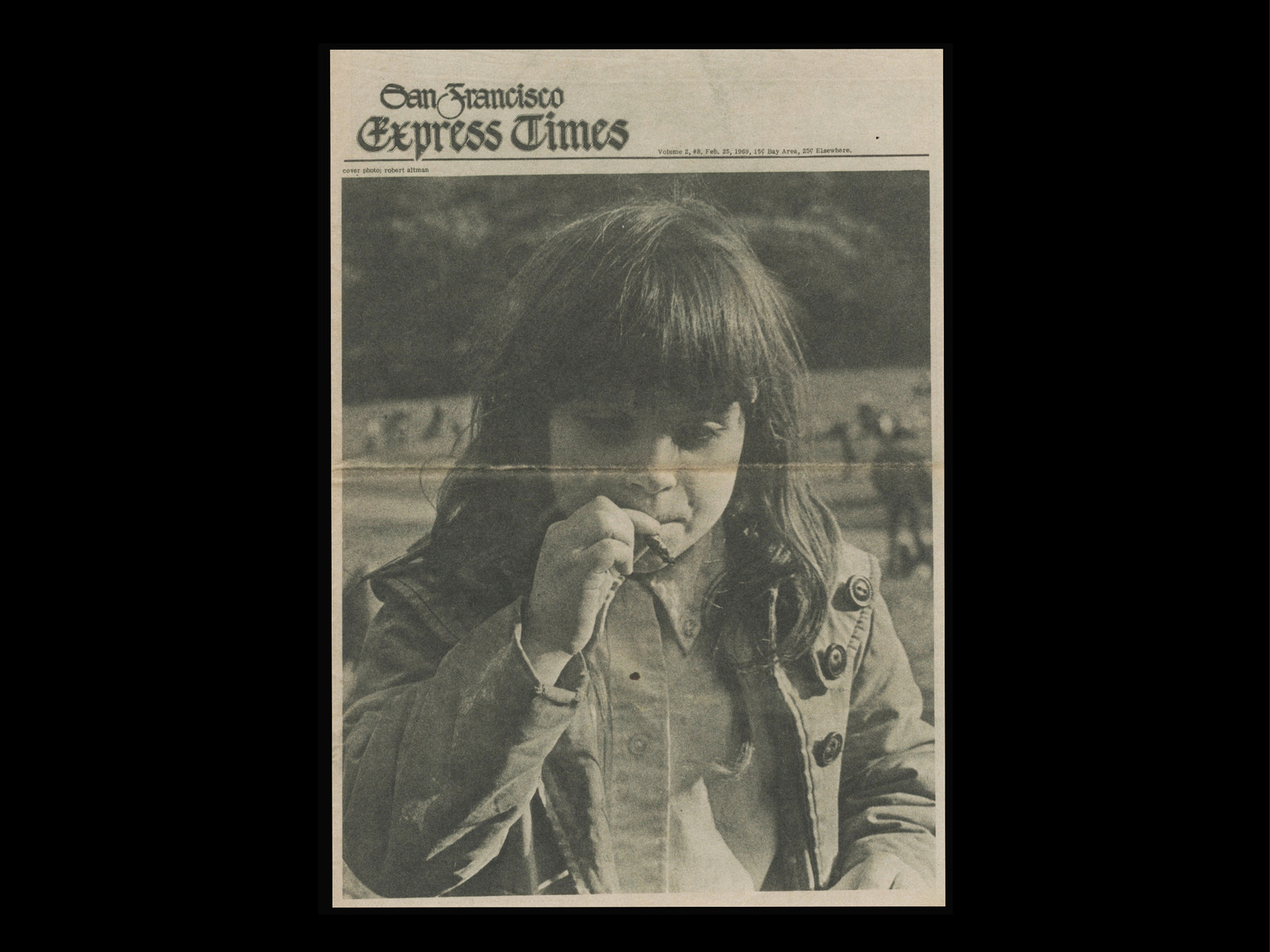

San Francisco Express Times (1969)

Left: it (formerly The International Times) (1972) / Right: it (formerly The International Times) (1968)

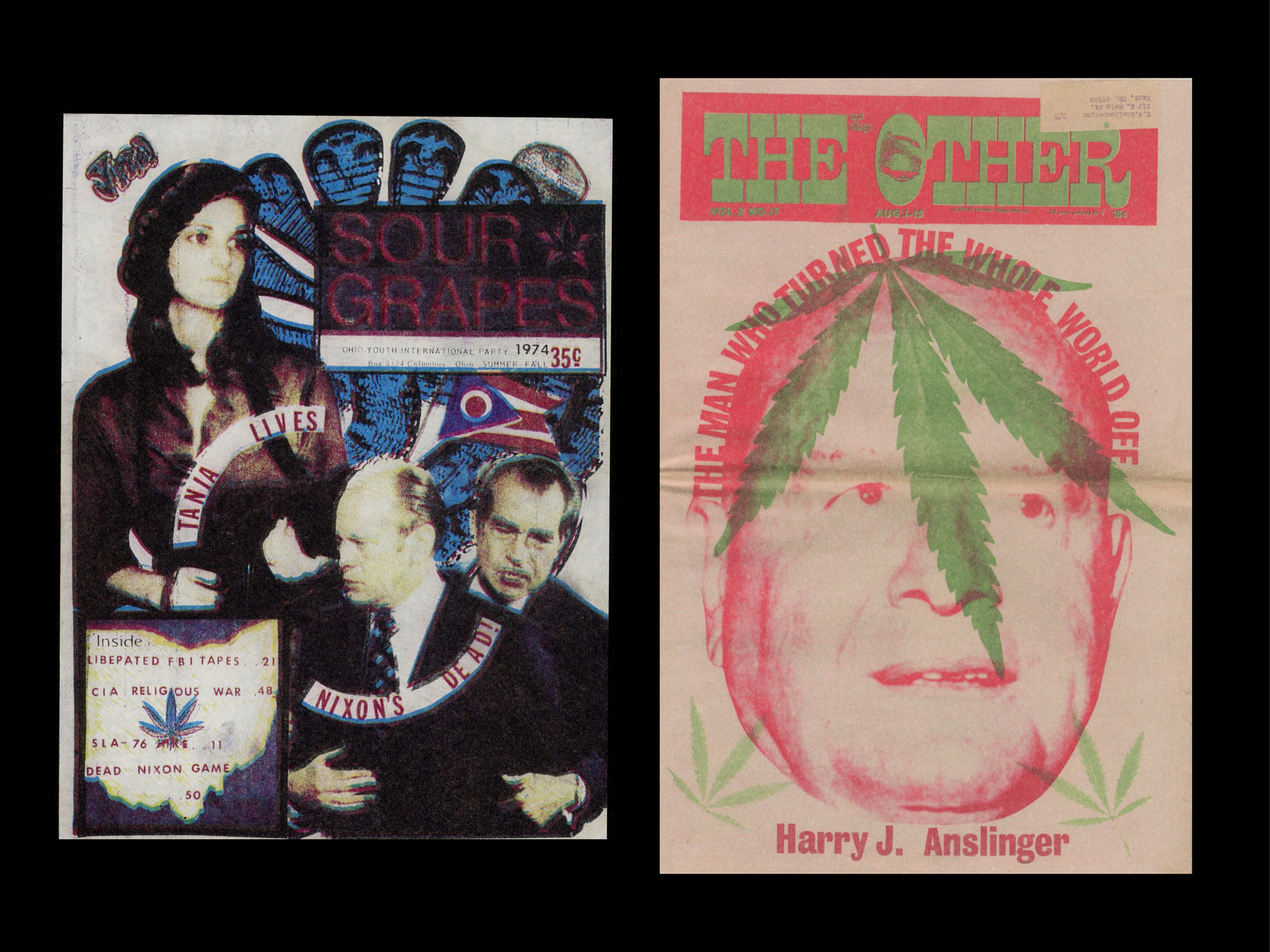

Left: Sour Grapes (1974) / Right: The Other (1967)

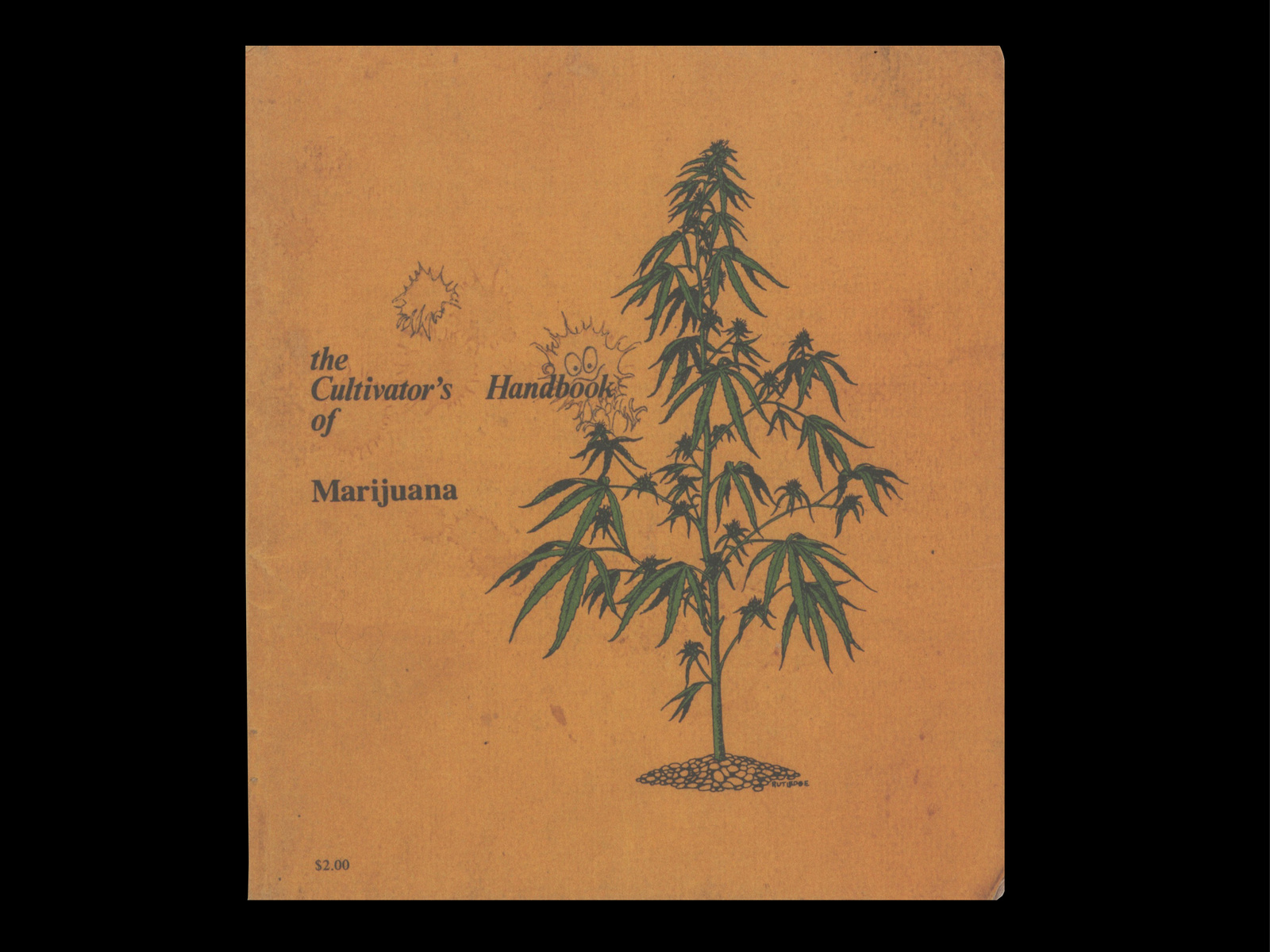

Cultivators Handbook of Marijuana, Bill Drake, 1970

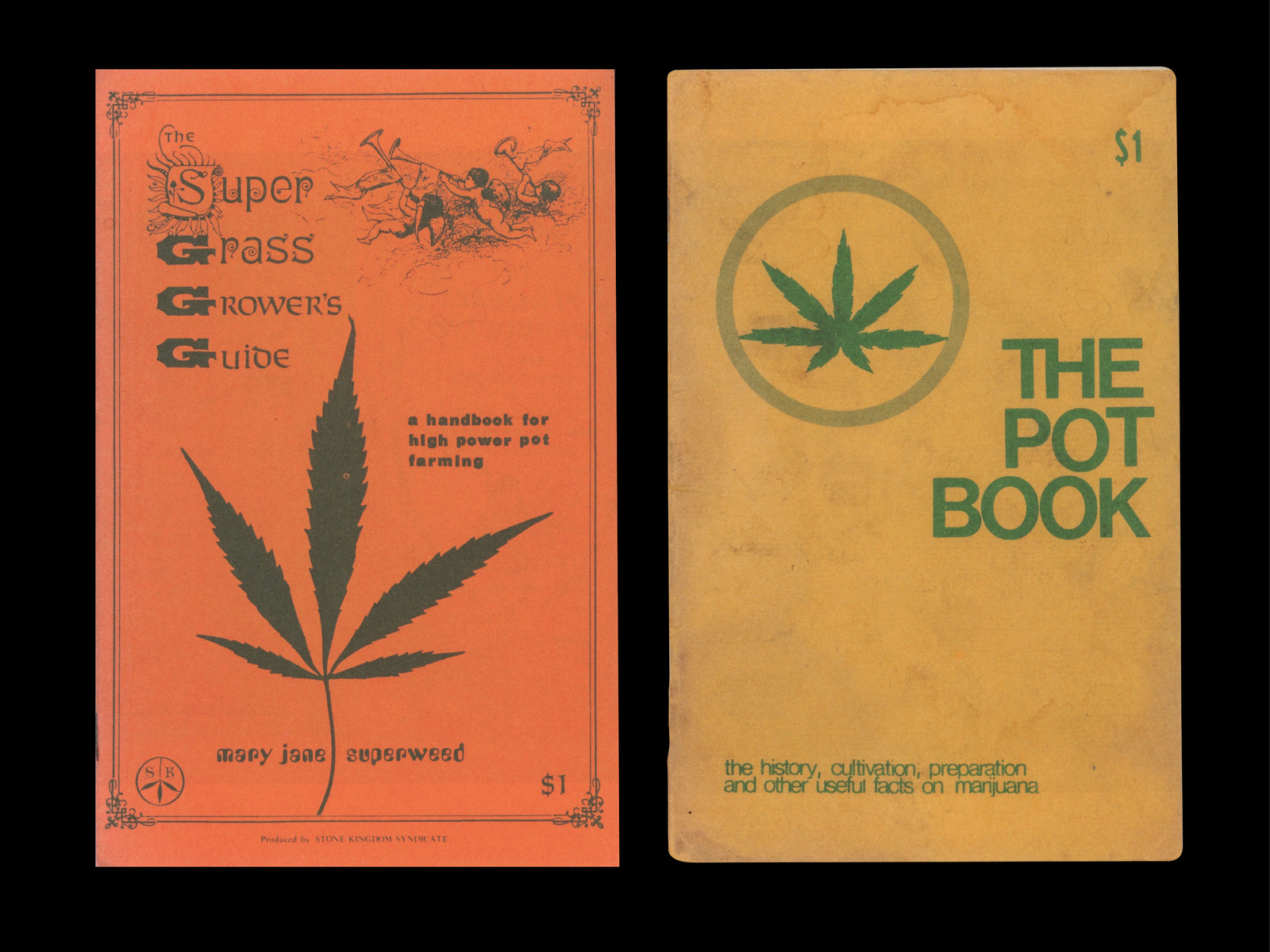

Left: Super Grass Grower’s Guide: A Handbook for High Power Pot Farming, Mary Jane Superweed (1970) / Right: The Pot Book, Most West (1968)

Weed and its image was put through a neoliberal, performance- and profit-orientated commodification process. Big weed now encompasses dispensaries in California that look like Apple stores, actors and musicians like Seth Rogen (Houseplant) or Jay-Z (Monogram) propagating their weed-lifestyle brands, or pivoting to marketable descriptions like “flower” in order to be read as a product of wellness culture. And indeed, Young concludes in his statement from 50 years ago: “The endpoint will be the commodity marijuana, in packets of machine rolled joints…Suitably diluted to be little more than a tranquilizer.”

Houseplant weed packaging

This foretelling became true, though only for an affluent, mostly white, and therefore often influential demographic (a sanitized weed industry does absolutely nothing for those still incarcerated by the ongoing war on drugs). And as the legalization of cannabis reframes the substance as a lifestyle product, the current and on-going capitalist treatment of psychedelics expands on that, with another central item of countercultural self-perception falling victim to an ideological takeover. Weed’s legalization could best be described as the canary in the coal mine. The current fixation on psychedelics—and the race to legality—affirms its trajectory, though with different consequences. Instead of only focusing on their recreational value, the medical value of psychedelics is put front and center which, compared to cannabis, makes for a different assemblage of stake- and shareholders, and different consequences in their look and feel.

What, these days, could best be described as the psychedelics space stands, aesthetically and intellectually, in stark contrast to its beginnings at the fringes of society. MDMA and ketamine-assisted therapy is explored as a cure for medical conditions such as PTSD (under which combat veterans suffer the most), Ayahuasca retreats are becoming a rite of passage for executives from the Silicon Valley, and the micro-dosing of LSD and mushrooms is applied by many actors of the creative class as a performance-enhancing practice in the service of increased productivity. The culture that claims psychedelics today is less concerned with the idea of a trip, and is instead funded and applied mostly by the ever-money-making one percent. Psychedelics are embedded more and more in a capitalist structure that monetizes and optimizes literally anything—even the spiritual. An observation which confirms that we are living in an age of recuperation, with once radical ideas and images becoming safe and commodified, ready to be marketed.

A NASCAR tweet celebrating Pride month

Many such cases can be identified, from what multimedia artist and writer Terre Thaemlitz calls the PrideTM model, which today is “completely market driven, inseparable from the ‘pink economy’ through which we have come to reconcile our LGBTTM self-images with capitalist process,” to adjacent protest movements or subcultural fashion and music. Before his death in 2017, Mark Fisher made this point already in in his unfinished essay “Acid Communism”: “The past has to be continually re-narrated, and the political point of reactionary narratives is to suppress the potentials which still await, ready to be re-awakened, in older moments. The Sixties counterculture is now inseparable from its own simulation, and the reduction of the decade to ‘iconic’ images, to ‘classic’ music and to nostalgic reminiscences has neutralised the real promises that exploded then. Those aspects of the counterculture which could be appropriated have been repurposed as precursors of ‘the new spirit of capitalism.’”

Seth Rogen promoting his weed brand Houseplant

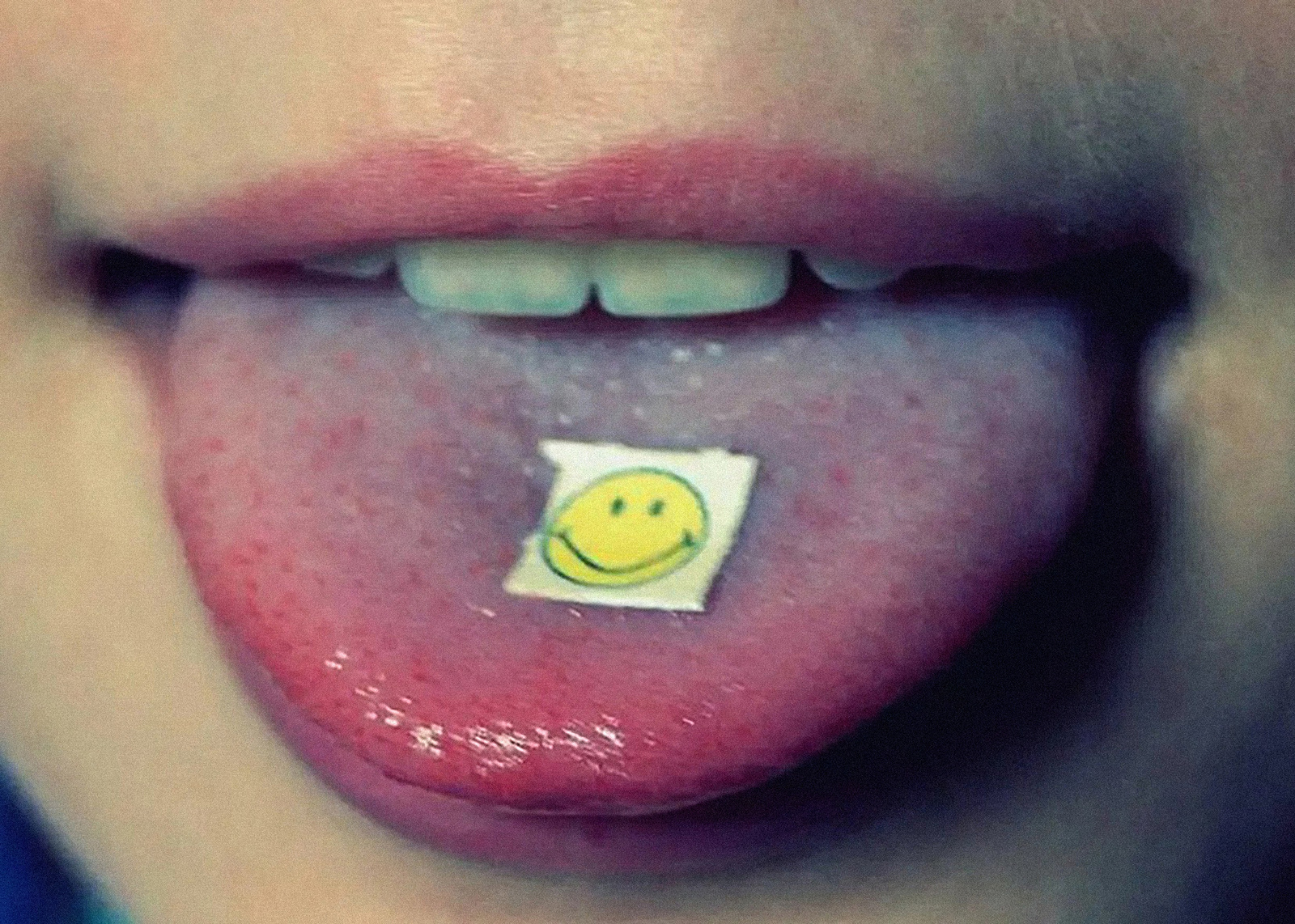

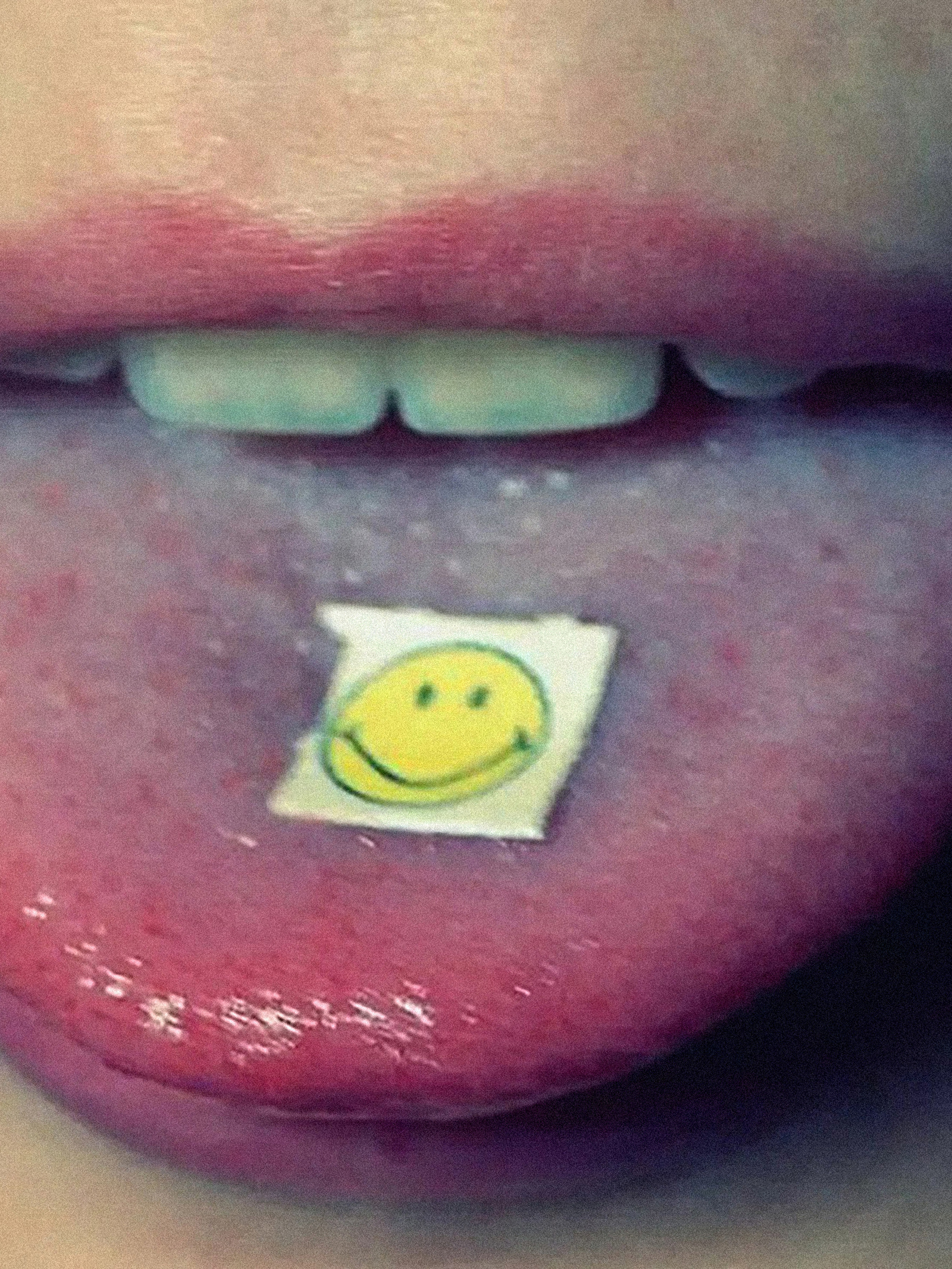

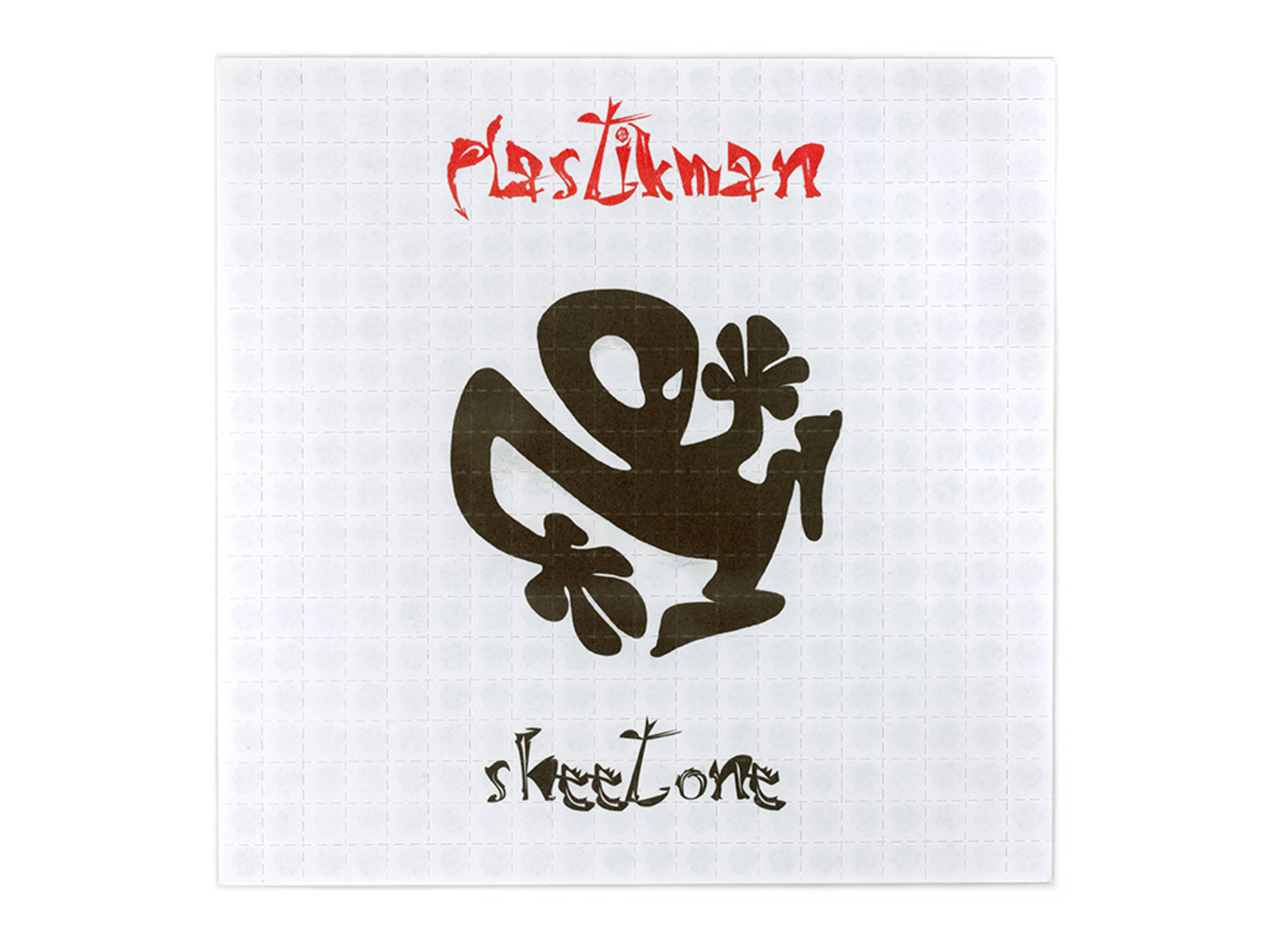

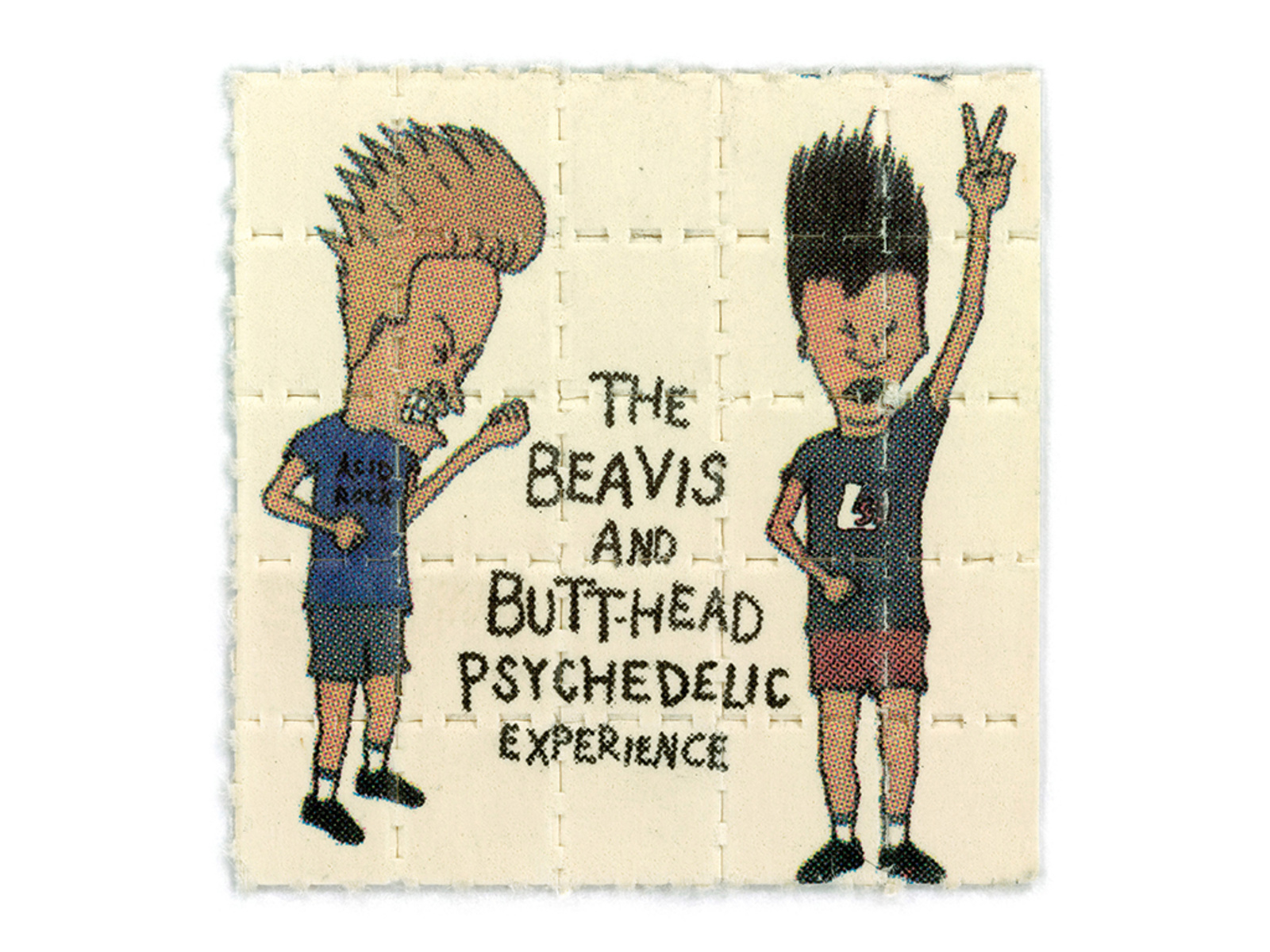

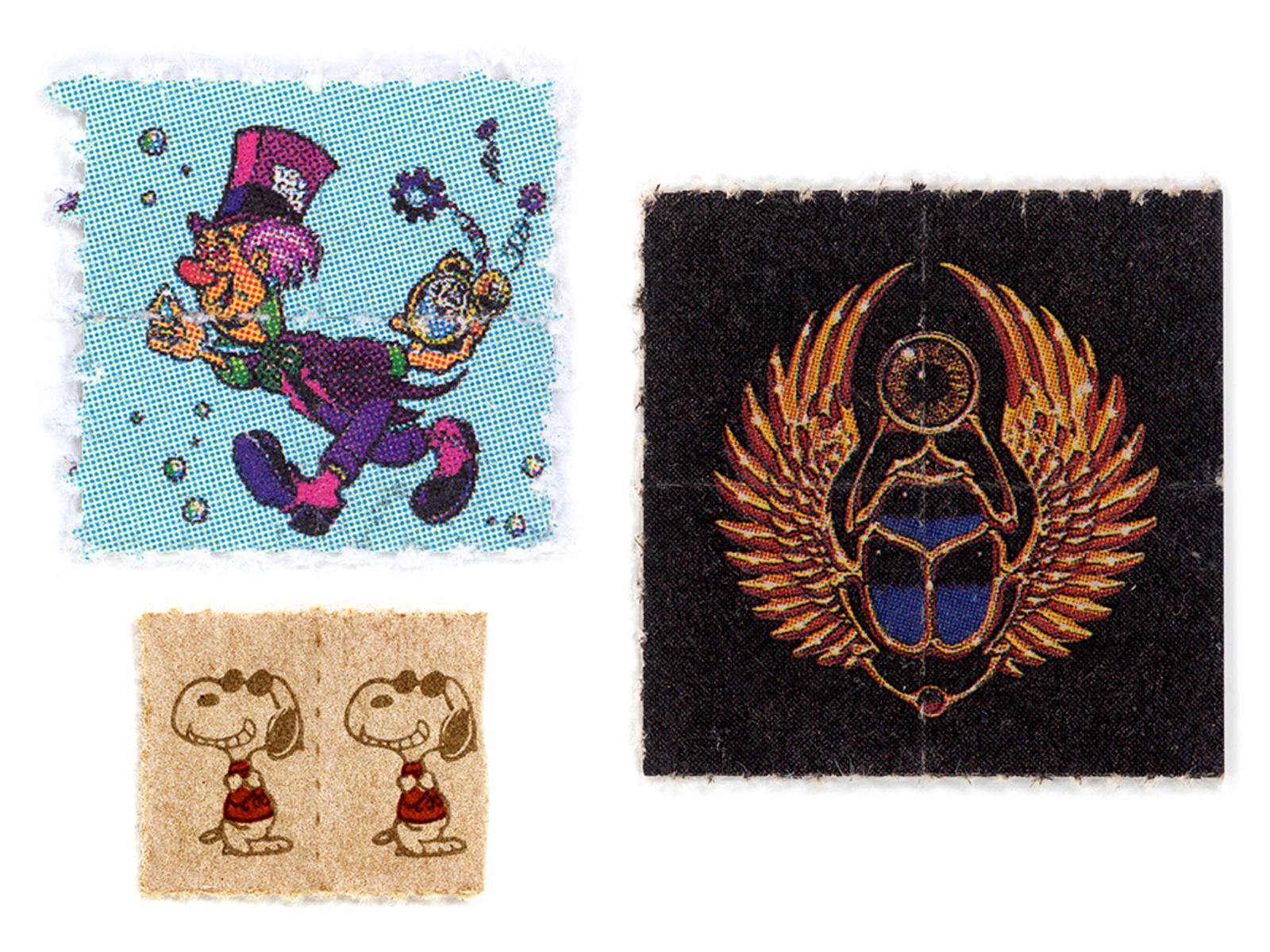

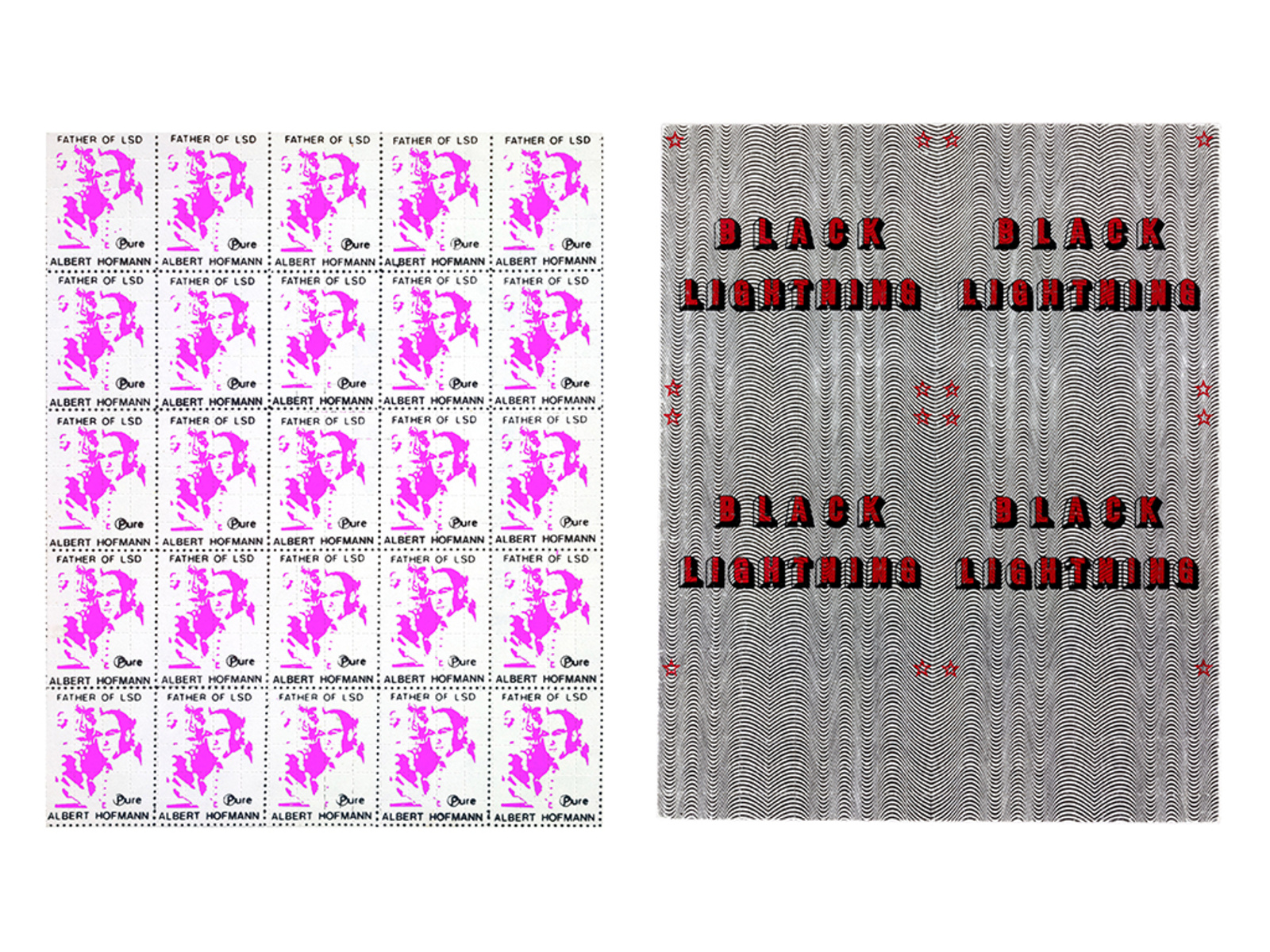

Blotter sheets from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheet from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheets from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheet from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheets from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheet from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheets from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheet from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

Blotter sheets from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn

One can only wonder what another Mark would have to say to this statement. Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn, which he established in his own house right in the middle of San Francisco’s ex-hippie Mission District, is the most comprehensive collection of decorated LSD blotter paper in the world. It’s an exuberant archive and a cabinet of curiosities alike, presenting hundreds of different sheets of acid paper that depict everything from Bosch’s painting The Garden of Earthly Delights, over, as it can be expected, a Grateful Dead logo, to aliens, Satanist symbols, Mickey Mouse as the sorcerer’s apprentice, or a smiling Snoopy in sunglasses. The collection’s visual richness and ambiguity allows for the tracing of various references and for serendipitous discoveries. It’s a testament for artistic self-expression as much as it is for a shared reference system which, in true countercultural fashion, worked against mainstream culture.

Mark McCloud

Dialectically speaking, the sheets of acid often indicate what the Situationist International defined as Détournement. This technique, initially coined in the late 1950s, sits at the opposite end of the term recuperation and is explained by Douglas B. Holt as “turning expressions of the capitalist system and its media culture against itself.” Differently put: one could expose themselves to the propaganda of a Disney movie, or one could trip on Mickey Mouse-adorned acid and create their own ideas about life.

McCloud’s archival endeavor could be described as a portal through which it’s possible to understand the countercultural and “OG” approach to psychedelics and its aesthetics at a distinct moment in time. It could also be described as a relic or fossil in a profoundly changed city and culture—McCloud saw the countercultural movement, in California specifically, come and go firsthand, and he’s doing important work in preserving an archive of what has been. His Victorian house in the Mission District is one of the few remnants amidst plenty of “gentrification gray.”

It’s in this city where psychedelics now meet corporate agendas, being rediscovered and rebranded as capitalist tools. Due to emerging research on various benefits of their therapeutic use—as treatment for mental health conditions, such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder—the legal landscape of psychedelics is changing globally. Countercultural or, for that matter, indigenous approaches to psychedelic drugs like LSD are diminished as venture capitalists are latching on. Idealism gives way to pharma economics with money pouring in via start-ups that are racing to be among the first to sell mind-expanding drugs as medical treatment. The global psychedelic drug market’s size was valued at almost three billion US dollars in 2023. It is projected to reach over ten billion dollars by the end of this decade.

Accordingly, changes in the look and feel of psychedelics are applied to make the drugs marketable and more broadly accepted: the contrast between the DIY and grass-roots anti-establishment aesthetics of psychedelics in the ’70s and its current iteration is striking. Companies working (read: investing) in the psychedelics space have names like Compass Pathways (“We connect science and compassion to reimagine mental health care”), Usona Institute (“Connecting Science and Human Well-Being”), Palo Santo (“Funding a New Paradigm in Wellbeing”), and MindMed (“Rethinking Brain Health”). Corporate aesthetics linger—coated with the vague promise of a brave new world—evoked, for example, by an adequately diverse representation of people through stock images, testimonials, or road maps that highlight the progress which has been made towards institutional recognition.

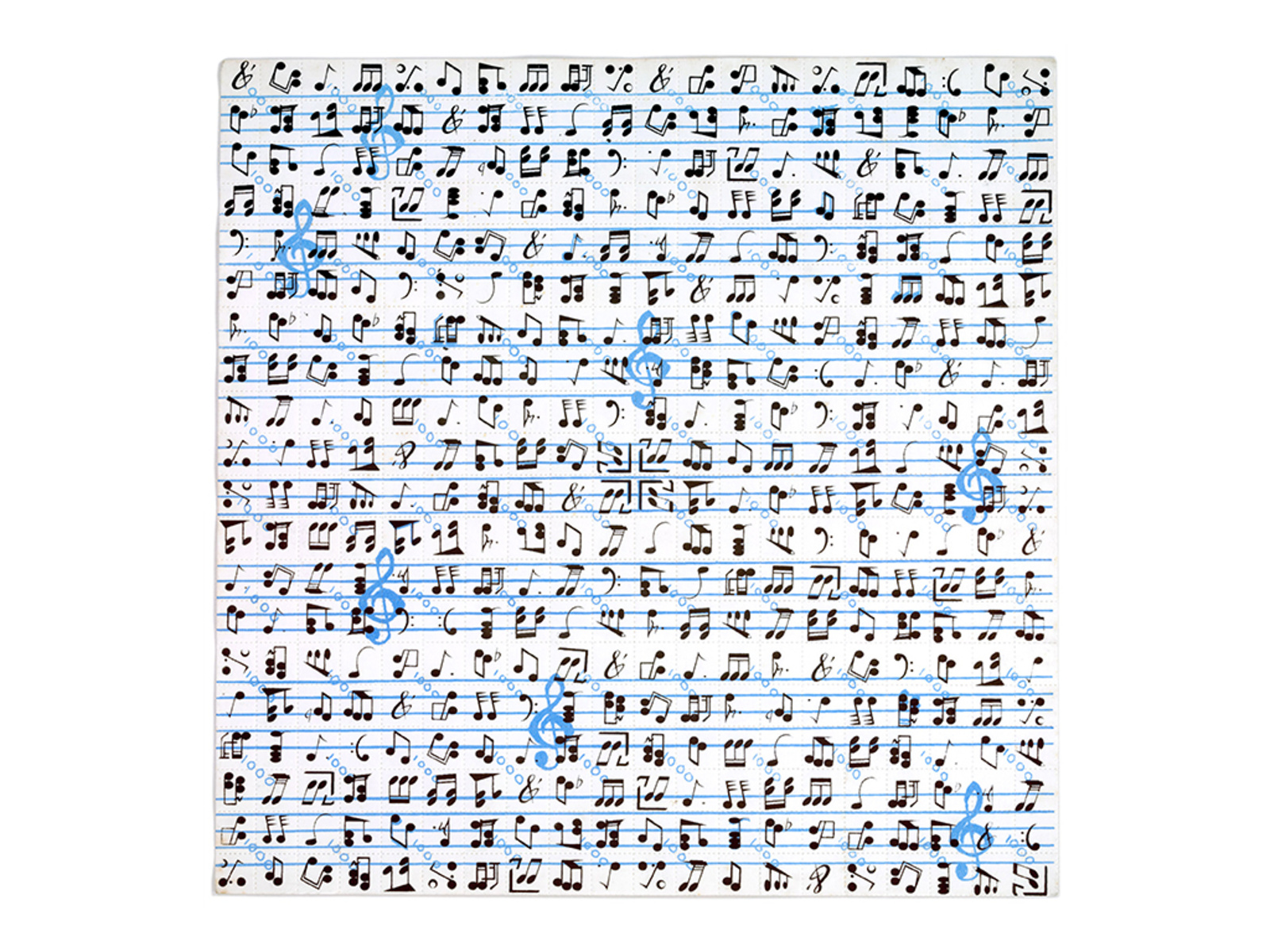

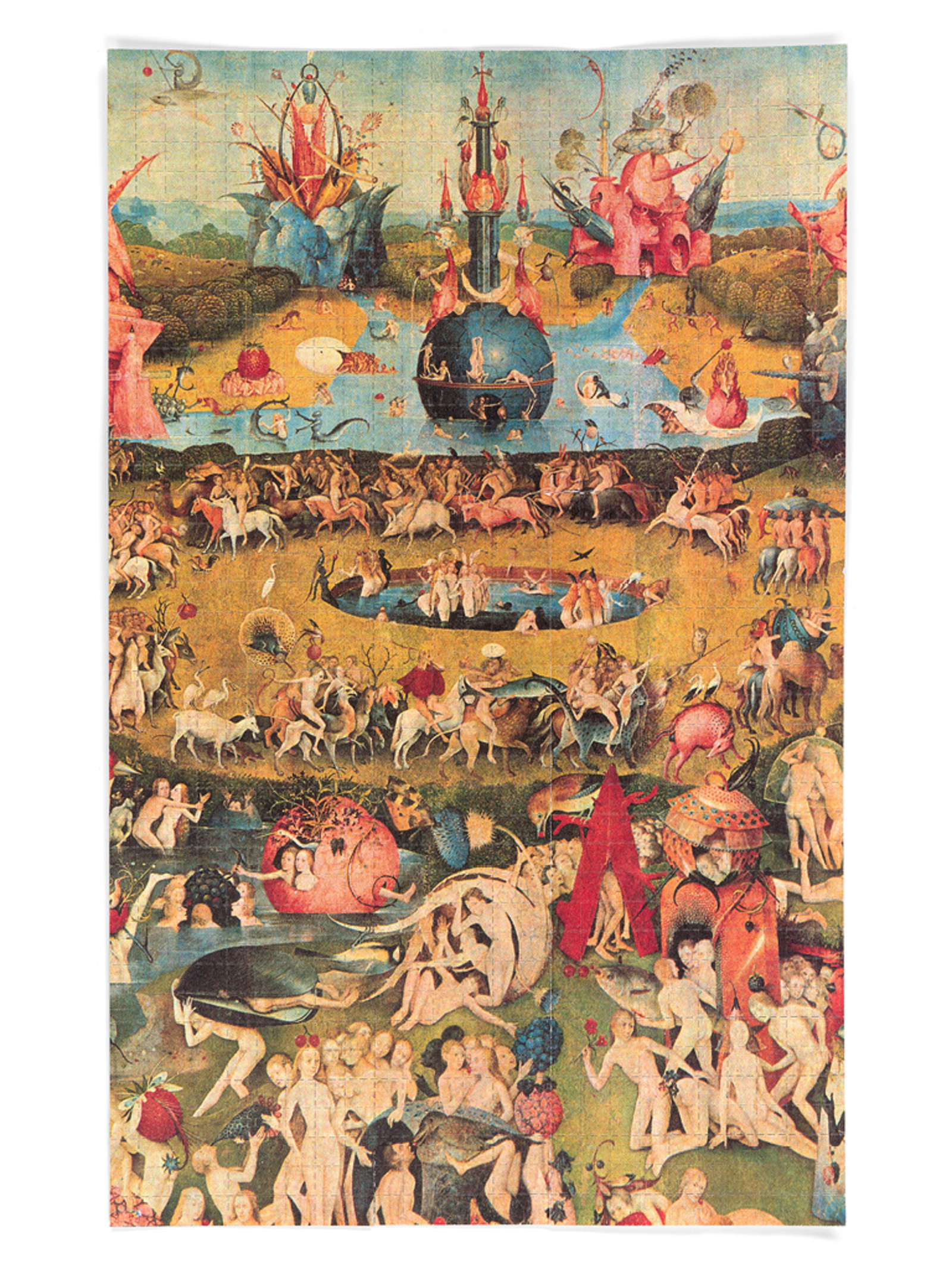

Blotter sheet from Mark McCloud’s Blotter Barn depicting Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510)

Measuring Psilocybin micro-doses in a laboratory

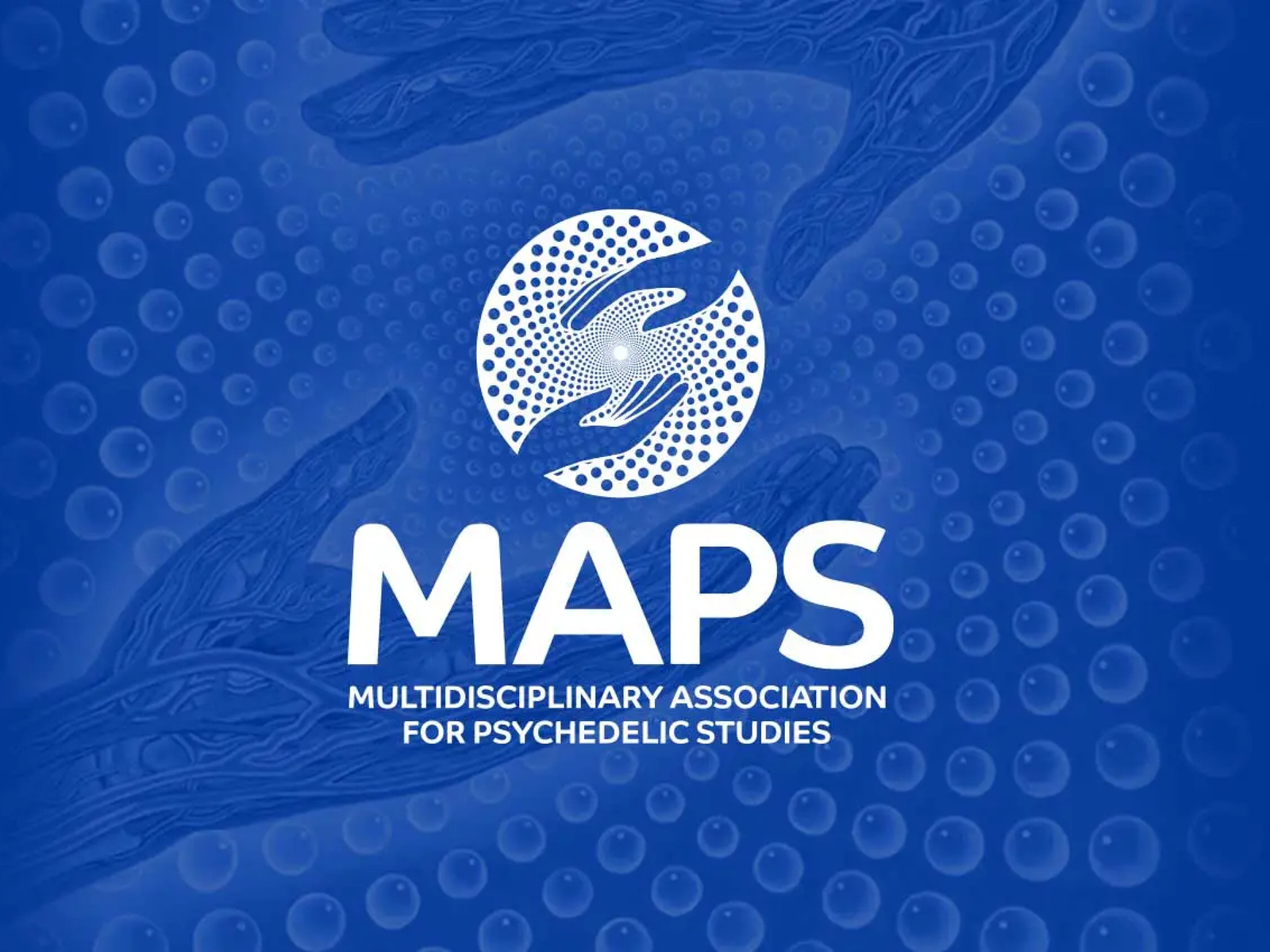

At the center of this fringe-mainstream conundrum sits a company formerly known as MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies). The company’s founder, Rick Doblin, has been interested in drugs and their potential for medical use since his studies in the late ’70s and early ’80s. He founded MAPS in 1986 and since then has pursued a lengthy and costly—the average cost to bring a new drug to market sits at around $1 billion—Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) approval process, hoping mainstream acceptance of MDMA therapy could positively impact access to other treatments. (A process that’s experienced a significant set-back in August, when the FDA rejected MDMA as a psychiatric treatment and requested additional research to prove the drug is safe and effective, which might take many more years.)

MAPS logo, designed by Alex Grey

Over decades, MAPS collaborated with scientists, raised funds through philanthropic means, and worked to change public perceptions of psychedelics. Importantly, MAPS for the longest time was a non-profit endeavor, relying on donations by individuals for psychedelic research and advocating for decriminalization. Eventually, though, they rebranded as a pharmaceutical company in January 2024. An initial Series A funding round brought in $100 million, almost as much as the nonprofit MAPS raised in donations in the 37 years prior ($140 million). The rebranding discarded the original, Alex Grey-designed logo and came with a new name, which denies any direct reference to psychedelics for something that reads like a sleek product of the Silicon Valley: Lykos Therapeutics, in line with the other actors in the field, wants to “break barriers and inspire change in mental healthcare,” as their website informs. More cynically summarized by Dennis Walker in the magazine Double Blind: “The golden beacon of hope that was once a non-corporate psychedelic leader has definitively folded into a business-as-usual pharmaceutical conglomerate driven by shareholder capitalism and intense regulatory scrutiny. The roots have become the suits.”

Lykos Therapeutics logo

Maybe this shouldn’t be surprising. Asked about psychological research into the benefits of psychedelics back in the countercultural ’60s, Doblin stated in an interview from 2019: “The cultural use was all about tearing down the system. Timothy Leary was very romantically attached to the idea of being the rebel. In 1990, I asked Leary, ‘Based on your long experience with psychedelic research, what is your advice to us about how to try to bring back psychedelic research and make it into medicine? How do you suggest we work with the government?’ He said, ‘I am so far past asking the government for permission for anything, but I’m glad you’re doing it.’ So, he’s like: ‘Fuck the government.’ And we’re like: ‘Let’s become mainstream.’”

While Timothy Leary, once deemed by Richard Nixon as “the most dangerous man in America,” forever remained anti-establishment, Doblin decided to position his endeavor more closely to the mainstream, with the aesthetics to match. The hippies and their psychedelic culture are finally dead—these days it’s about the substance’s benefits to health and wellness. Browse the Lykos homepage and you’ll be confronted with terms like “patients,” “therapy,” “treatments,” and “healthcare,” with graphs that inform about the focus on “people,” “governance,” and “innovation.” Psychedelics, which were once cherished as an opportunity to let go of control and for their spiritual potential, are now more and more becoming sterilized tools to enact control, properly integrated into capitalist structures. And just like with cannabis, psychedelics’ liberalization in society leads to a commodification of that newly acquired liberty.

In this process, psychedelics and venture capital become bedfellows in a narration of the optimization of the self—which is ultimately a narration of productivity—with the drug being rebranded as a safe (read: controllable) and sanitized tool. The “estrangement” that Benjamin was anticipating to occur between generations is applied as a strategy: to obscure psychedelics’ deviant beginnings at the fringes of society, the substances are cleared of their history. Literally and figuratively, as Mark McCloud’s archival project reminds us.

“The Great Turn” (2019) by Alex Grey, the artist who designed the original MAPS logo

The psychedelic turn announces itself with severe aesthetic consequences, and as a result, our idea of the drugs is changing in real-time. For now, they possess a split personality, with their roots in countercultural ideas and their medical use gaining ground. While it’s justified to be hopeful about their successful application as treatment, it’s also necessary to consider who profits most from this development. It might be those who suffer from medical conditions such as PTSD, anxiety, or addiction, but it might also be those who are able to capitalize on exactly these treatments. Once again, whether a drug is accepted by society or criminalized has little to do with its effects, and everything to do with how valuable it is to certain interests: and these days, a lot of pharma companies and investors are pushing into the psychedelics space. As the example of MAPS-cum-Lykos proves, interest clearly spikes when the possibility to donate is transformed into a possibility to invest.