Stories of Smoke and Mirrors

In one of artist Nan Goldin’s best-known works, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1979–1986), she captures herself and her friends in downtown New York living their lives fully, presented as a slideshow set to a shifting soundtrack. Under the influence of everything, random gestures become meaningful moments, depicting the highs and lows, the ecstasy and pain, of chosen family. The work is emblematic of Goldin’s artistic practice, which often connects collective societal matters with the deeply personal. Her work opens up complicated questions about the relationship between self-documentation and exploitation, especially since she and her muses at the time were so often high on heroin. Ultimately, it’s the raw intensity that only someone so close to their subject matter can capture that makes the work so arresting. By not sparing herself or her friends, treating them with brutal honesty, Goldin puts forward a proposal for what it means to create art with integrity and transparency — a powerful counter to the structural injustice, and the entanglement of branding and patronship, in the art world.

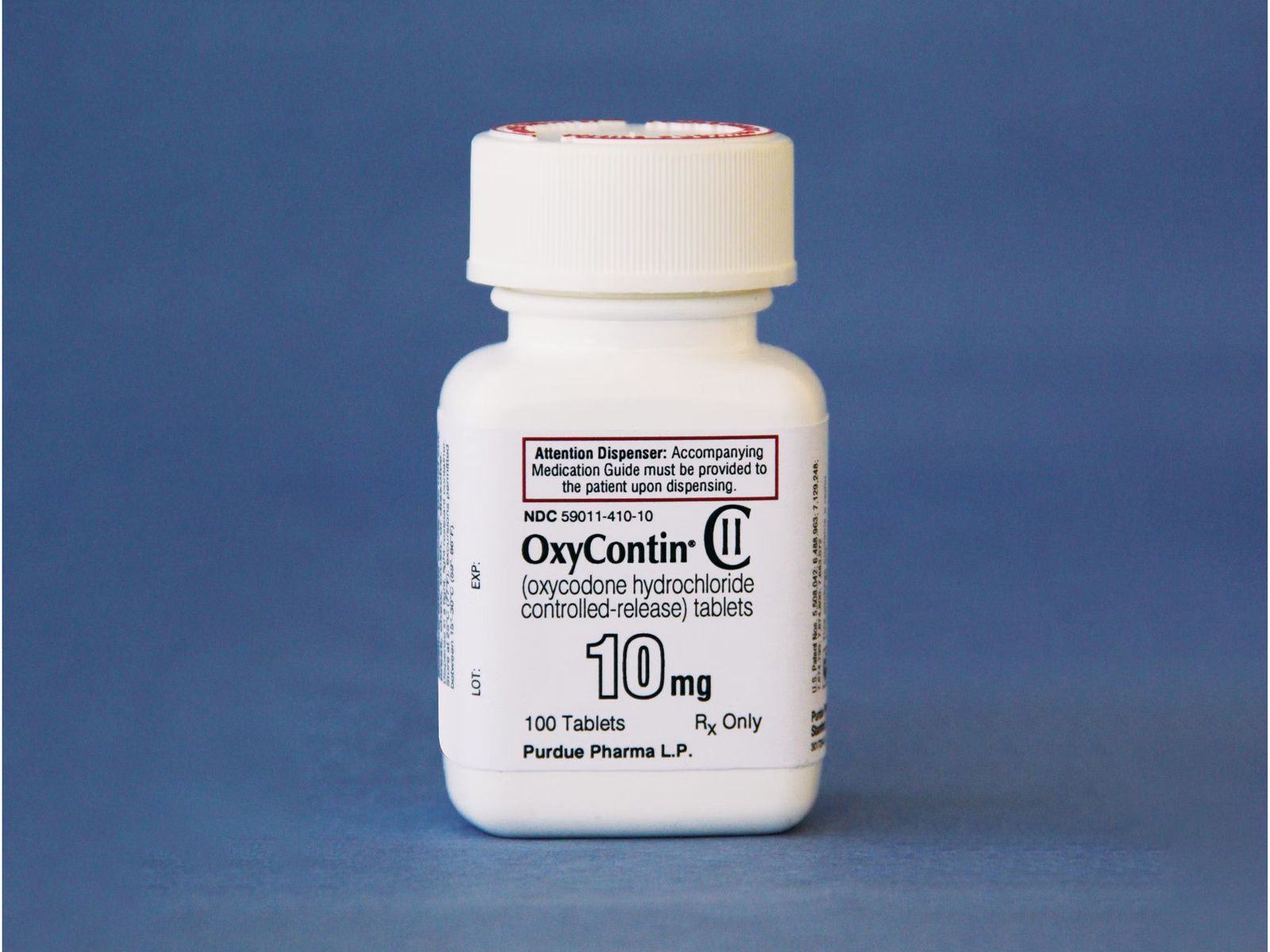

Eventually, Goldin got sober, but not without taking an unfortunate detour: in 2014, she was prescribed the potent narcotic OxyContin due to wrist pain. Recounting her initial experiences with the drug to The Guardian, she says: “The first time I got a ‘scrip it was 40 milligrams and it was too strong for me; they made me nauseated and dulled. By the end, I was on 450 mg a day.” In the January 2018 issue of Artforum, Goldin presented a portfolio of images that chronicle her history with OxyContin, which was invented in 1995 by the Connecticut-based company Purdue Pharma, and has since made the company a fantastical fortune. At the time of its release, the drug was branded as a revolution of the painkiller market: in contrast to other opioids, OxyContin was designed to be released slowly into the body, promising longer pain relief and diminished potential for addiction. It’s a legal drug prescribed to around a third of the US population per year with a formula that emulates a concentrated and chemical version of heroin. Both are members of the opioid family, which significantly impact the brain and nervous system. A 2022 study by Mohammadreza Azadfard, Martin R. Huecker, and James M. Leaming informs about the drug’s potential for abuse: “Opioid use disorder and opioid addiction remain at epidemic levels in the US and worldwide. Three million US citizens and 16 million individuals worldwide have had or currently suffer from opioid use disorder (OUD). More than 500,000 in the United States are dependent on heroin.”

Seeing the effects of heroin and later OxyContin on Goldin’s life through her work opens up a throughline for analysis between the two drugs. Both have had devastating effects on society, but the reaction of the state — deeming one legal and one illegal — has created profoundly different conditions within which they operate. In another act of artistic self-documentation, the photographer Graham MacIndoe’s 2014 book ALL In: Buying into the Drug Trade traces the marketing of heroin through the stamped designs adorning the glasseline bags used to package and brand it. Taken together, these two artists’ works show that a drug’s status as legal or illegal dictates not only their distribution methods and thus margins of profit, but also how they are branded and visually communicated to the world. Marx spoke about a society in which “every product of labor [is transformed] into a social hieroglyphic” that has to be deciphered, tracing them as real artifacts in the social world, rather than containing them in established rules of interpretation. How, then, can we interpret the visual language, or lack thereof, of these two drugs which are so close to each other in everything but their legal status?

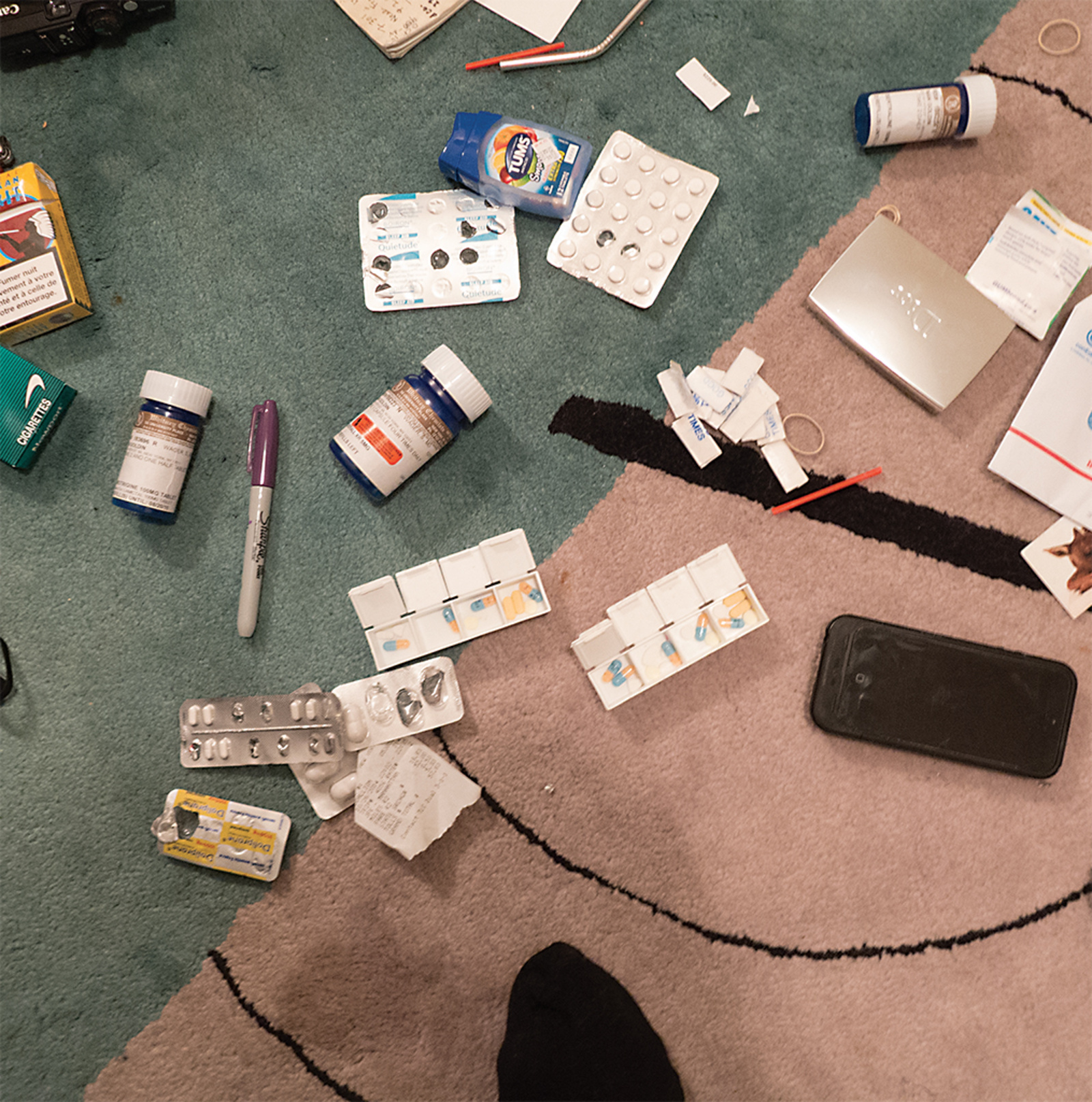

Nan Goldin, Dope on My Rug, New York, 2016.

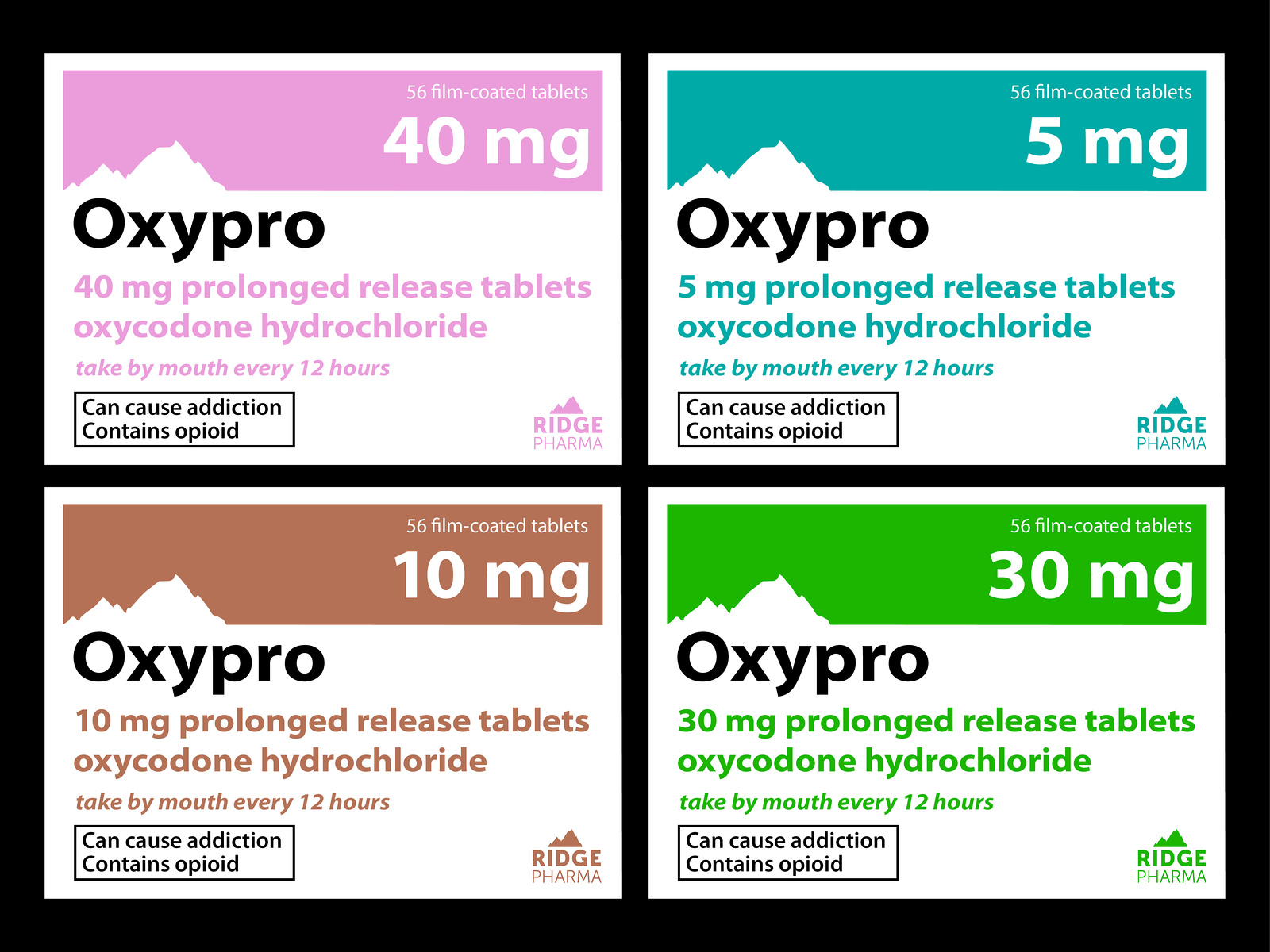

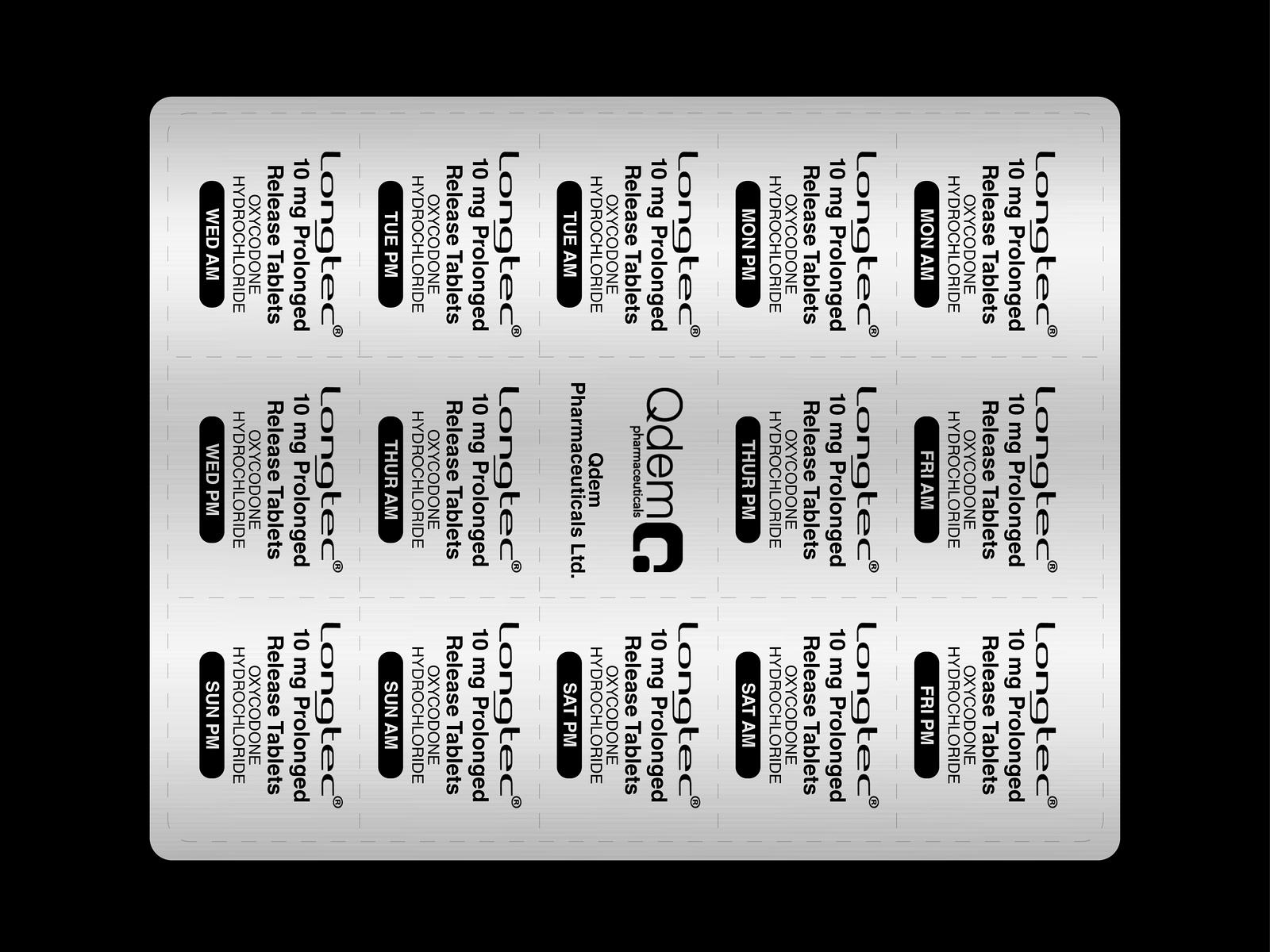

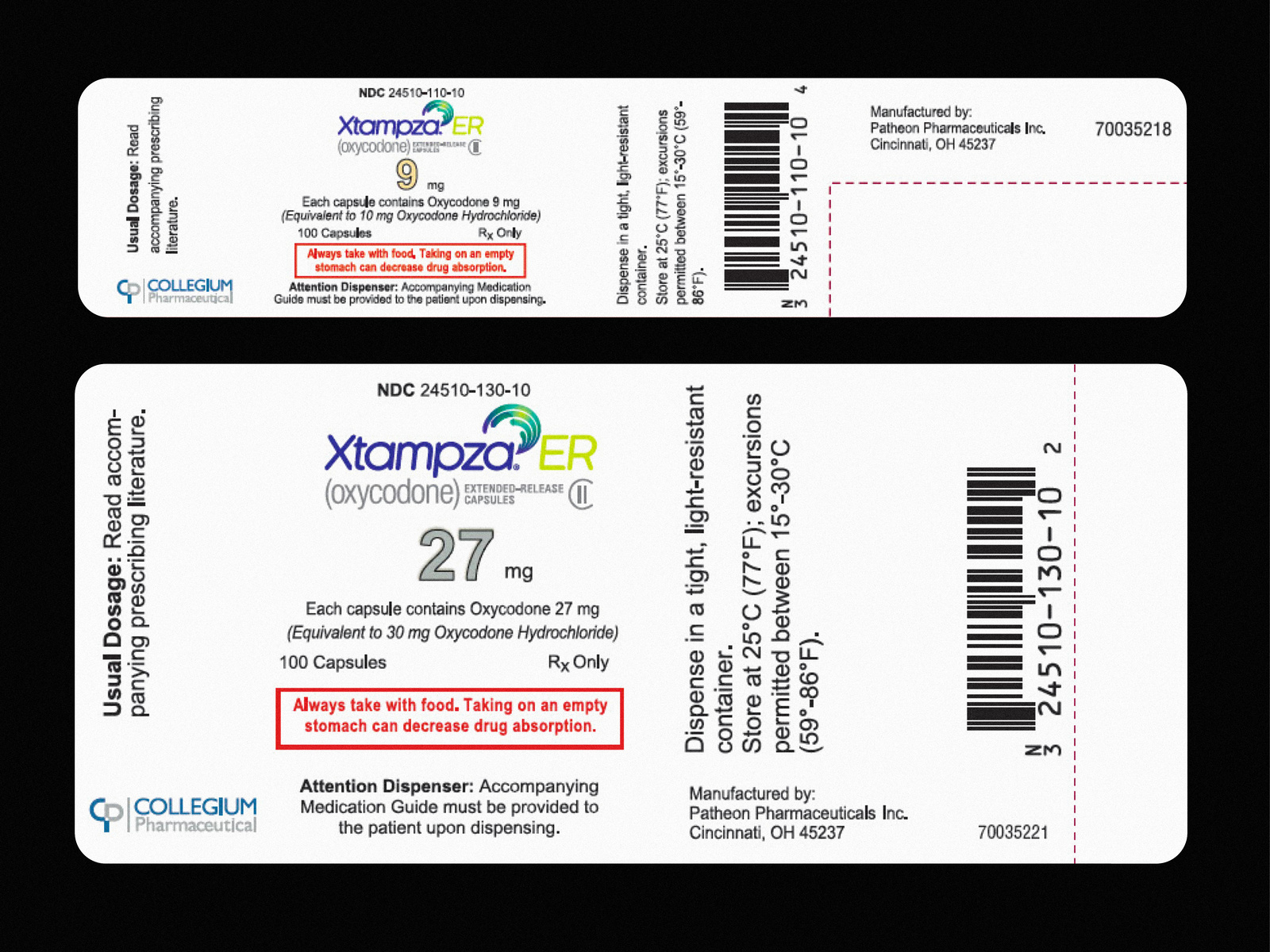

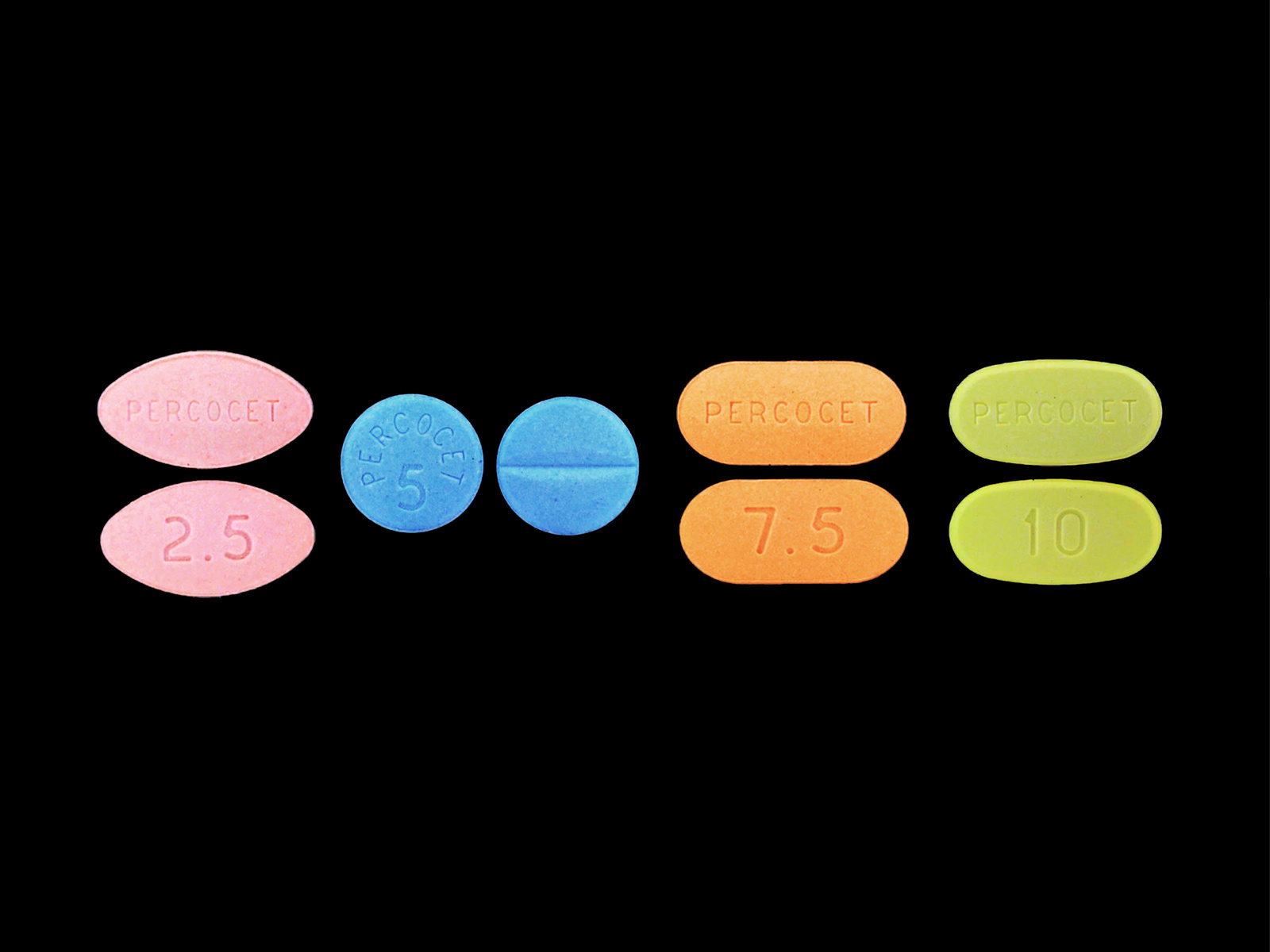

The opiate Oxycodone is packaged under a variety of brand names, perhaps the most well known being OxyContin from Purdue Pharma.

Pill packaging design for Ixyldone, a brand name of Oxycodone.

Pill packaging design for Oxypro, a brand name of Oxycodone.

Oxycodone can also be injected with brands such as OxyNorm, which supply the opioid in vials.

Design of the back of pill packaging for Longtec, a brand of Oxycodone.

Pill label design for Xtampza, a brand name of Oxycodone.

Pill design for Percocet, a combination of Oxycodone and the non-opioid pain reliever Acetaminophen.

We’ll start with heroin. If seeing and depicting everything are the guiding principles of Nan Goldin’s work, it’s not a stretch to attribute the exact opposite to Purdue Pharma or, more precisely, to its owners, the Sackler family. The Sacklers have been described as “the most evil family in America,” and “the worst drug dealers in history.” Via Purdue, they have been identified as the prime driver of the opioid crisis in the United States. Over the last 20 years, the epidemic has killed more than 200,000 people and drove considerably more people into addiction. After patenting the drug, the patron of the family, Arthur Sackler, convinced doctors in the 1990s that OxyContin was harmless, seducing them first in order for them to seduce their patients second. In 2020, the family’s net worth was estimated to have exceeded $10 billion.

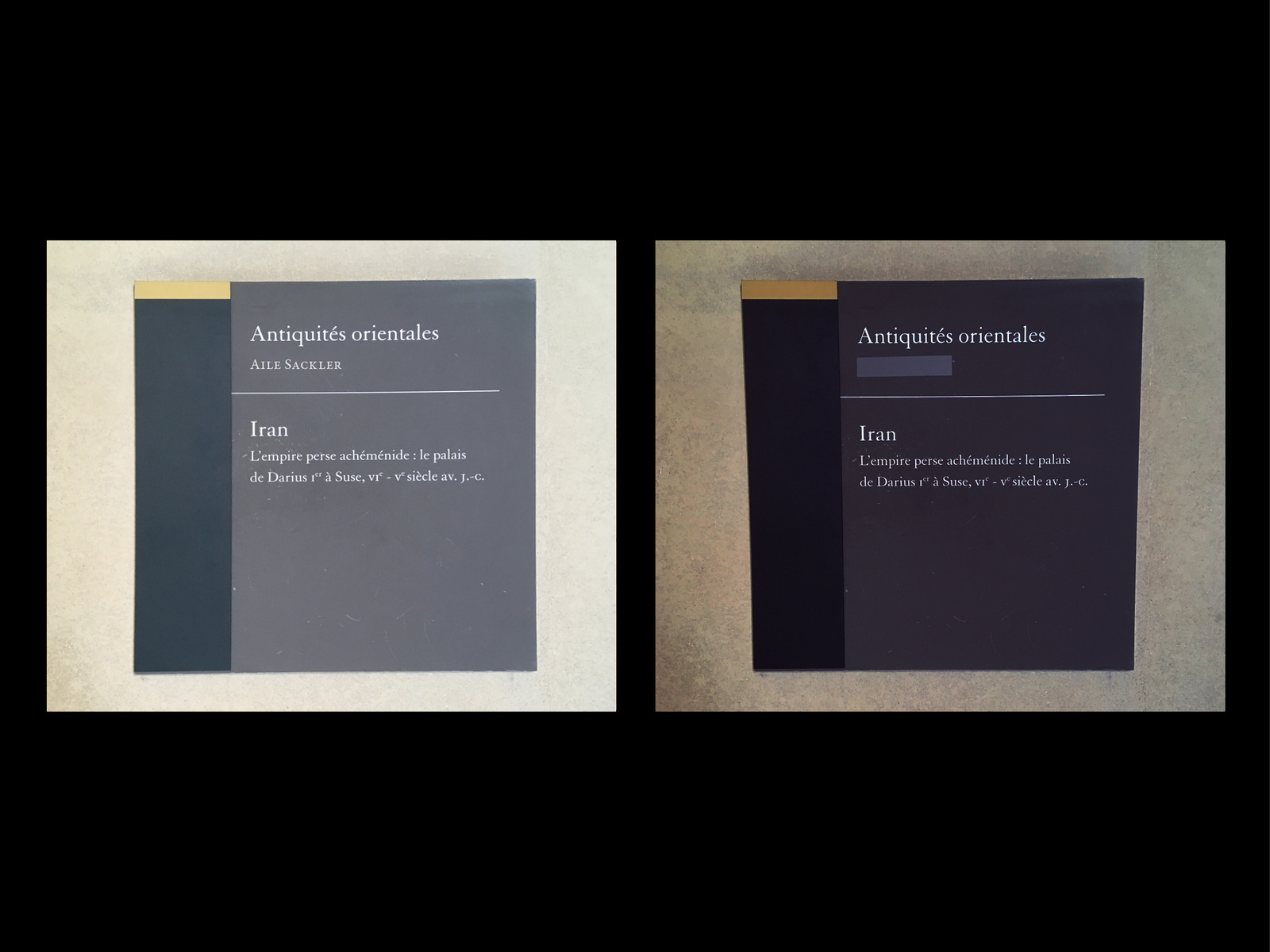

For years, deception was at the core of the business model. The Sacklers used their wealth and elite social status to brand the family name — without association to what actually generated the wealth. In a 2017 article for The New Yorker, journalist Patrick Radden Keefe lays out the family’s strategy of philanthropic smoke and mirrors: “Although the Sackler name can be found on dozens of buildings, Purdue’s website scarcely mentions the family, and a list of the company’s board of directors fails to include eight family members, from three generations, who serve in that capacity.” Instead of attaching the good family name to the pharmaceutical company they finance, it’s been pushed forward in all kinds of philanthropic endeavors, concealing the root of evil.

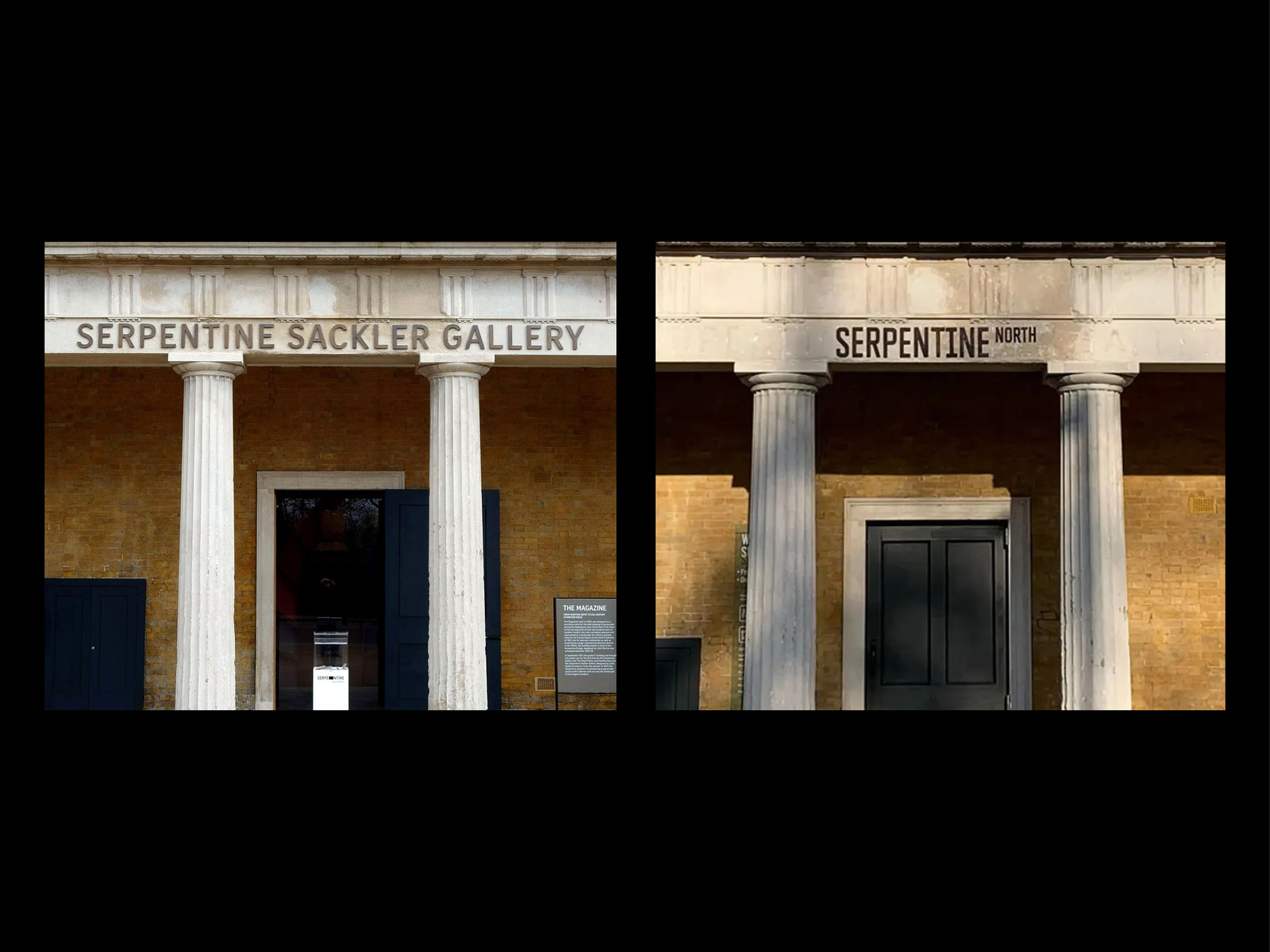

Many of the buildings bearing the Sackler name were cultural institutions around the world, among them the Louvre in Paris, the Serpentine Gallery and Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and the Guggenheim and Metropolitan Museum in New York. The latter two became stages for so-called “die-ins” orchestrated by Goldin’s activist group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), which she founded in 2017 in order to put pressure on institutions to remove the Sackler name from their buildings and donation receipts. Responding to this, in 2019, the artist Hito Steyerl had a show at the Serpentine Galleries in London, which included an augmented reality app through which visitors could see the building’s façade with the Sackler name notably absent.

Nan Goldin “die-in” at the Louvre, Paris (2019)

In 2021, the museum followed suit and removed the name in real life. A year later, an article in The New Yorker titled “Nan Goldin Visits the De-Sacklered Met,” follows Goldin on a visit to the New York institution together with the documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras, whose 2022 film All the Beauty and the Bloodshed follows Goldin’s activist endeavors and life. “One day last December, Goldin got a tipoff that the Met was finally scrubbing the Sackler name. ‘We screamed,’ she recalled. She and Poitras rushed to the museum: the lettering on the glass doorway to the temple was already gone, with just a smudge left. (Not getting to shoot the removal, Poitras admitted, was ‘a heartbreak.’) All in all, the Met erased the name from seven spaces.”

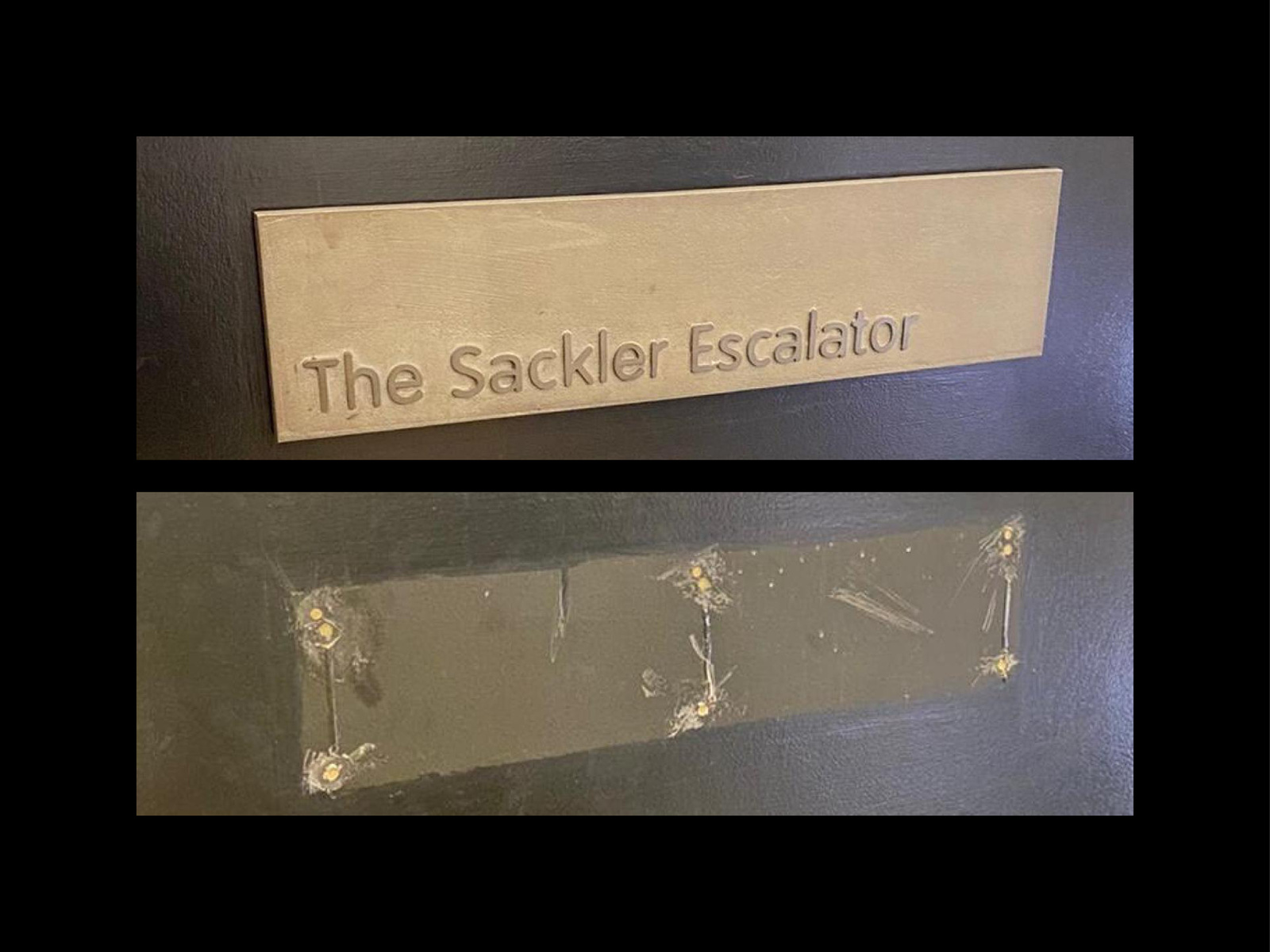

The “de-Sacklering” of museums — removing the Sackler name from their buildings and refusing further donations from the family — was a win for activists as much as it was a performance of high-art-adjacent bluffing: an underhanded act of absolution that veils these institutions’ ever-compromised dependency on external funding. It brings to mind another act of concealing, which only requires one to take away an “l”: in graffiti, the act of “buffing” refers to obliterating tags with a paint roller, creating an accidental aesthetic by leaving rectangular shapes of gray color. A buffed graffiti leaves a smudge in its wake, marking the presence of an absence, so to speak. A “buffed” museum creates a blank space without being able to dial back the consequences of the Sacklers’ actions. Even though the name is gone, the severe and lasting consequences the family and their company had on many people and entire communities can’t be obliterated.

Graffiti buffing

Like any drug dealer, the Sacklers’ aspired to be known but disguised at the same time — a double-bind achieved, in this case, by wealth and influence and the fact that, technically, they didn’t do anything illegal. A network of gatekeepers (the Sackler’s themselves, politicians, doctors, pharmaceutical lobbyists, etc.) provided the drug free passage from the top down for it to succeed in penetrating society on a big scale: the actors involved here create a context so murky and infiltrated that it becomes impossible to direct liability to any one entity. Instead, the Sacklers controlled the narrative, fed their narcissism, and bought influence by supporting the most established of cultural institutions with their drug money. Slapping their name on prime real estate, in golden letters and prominent places, they gained visibility and status as philanthropists on their own terms — until they didn’t, thanks to artists like Nan Goldin or Hito Steyerl.

Sackler name removal from Tufts University (2019)

Serpentine Gallery, London

Tate Modern, London

Louvre, Paris

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A counterpart to the regulated but corrupt widespread distribution of legal OxyContin and their creators’ desire to deflect from their involvement can be found in dealers’ activities in the unregulated, illegal, and hyper-local heroin scene of the 1990s and early 2000s New York. In fact, one black-market substitute for OxyContin has always been heroin (which was initially a licit drug invented by Bayer, a pharma company), and even more so after the pharmaceutical was reformulated in 2010 in an attempt to minimize the risk of abuse. Chewing, crushing, swallowing, snorting, and intravenous injection became harder as the pills got harder. Again Keefe: “This is one dreadful paradox of the history of OxyContin: the original formulation created a generation addicted to pills; the reformulation, by forcing younger users off the drug, helped create a generation addicted to heroin. A recent paper by a team of economists, citing a dramatic uptick in heroin overdoses since 2010, is titled ‘How the Reformulation of OxyContin Ignited the Heroin Epidemic.’ A survey of two hundred and forty-four people who entered treatment for OxyContin abuse after the reformulation found that a third had switched to other drugs. Seventy percent of that group had turned to heroin.”

While OxyContin and heroin are inextricably bound, their status as a legal or illegal drug, respectively, influences the conditions within which they operate in society. Heroin is found on the margins. There is of course plenty of discourse surrounding it; it continually seeps into popular culture (Kurt Cobain, Trainspotting, The Wire, The Velvet Underground, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop), but its distribution and usage happens in a more fragmented and decentralized manner than a prescription drug. MacIndoe’s book ALL In shows a glimpse of this method of distribution through the drug’s visual language and distributional aesthetics. If Goldin’s photographs and activist work make visible the source of the OxyContin epidemic, MacIndoe’s is a lesson in heroin’s clandestine branding.

Drug store sign for Bayer Heroin and Aspirin (1914–1924)

Photographs of stamped heroin bags from Graham MacIndoe’s book All In: Buying into the Drug Trade

Photographs of stamped heroin bags from Graham MacIndoe’s book All In: Buying into the Drug Trade

Photographs of stamped heroin bags from Graham MacIndoe’s book All In: Buying into the Drug Trade

Photographs of stamped heroin bags from Graham MacIndoe’s book All In: Buying into the Drug Trade

Photographs of stamped heroin bags from Graham MacIndoe’s book All In: Buying into the Drug Trade

Photographs of stamped heroin bags from Graham MacIndoe’s book All In: Buying into the Drug Trade

Photographs of stamped heroin bags from Graham MacIndoe’s book All In: Buying into the Drug Trade

Born in Scotland but living in New York City, MacIndoe documented the heroin bags he collected during years of addiction. Each image is a variation of glassine bag with stamped branding — often dark and sometimes subtly ironic, with names like “9 Lives” or “All In,” clearly referencing the risks of a heroin addiction. Others, with the Rolex logo or a plane with the words “First Class” underneath create the illusion of luxury. Some are fairly on the nose about the potential end game: “Get Fucked Up,” “Dead Medicine,” “Killa.”

These marks have a delicate dual-function: their purpose is to lead buyers back to the source, while simultaneously evading the authorities. Similar to the Sackler name, heroin dealers need to be visible in some contexts, and invisible in others. To do that, they appropriate symbols from mainstream culture and enter them into new systems of meaning: the stamps serve an expressive function, constructing attitudes about heroin and the lives and roles of users and distributors. In his book’s foreword, MacIndoe says: “I can’t even begin to measure the time spent trekking out to the projects in search of a particular kind of heroin. You’d hear word on the grapevine that High Life was bomb or that Diesel was sold on a corner in Brooklyn. The rumors helped keep the market flowing. From time to time, the dealers would put out a batch that was really strong to make you keep coming back. Then when they had reeled you in, they’d dilute it again. In a way, they nurtured their regular clientele, leading them down the road to a brilliant promise: this product will change your life.”

MacIndoe’s images tell a story of the seductive powers of marketing and consumer culture, of which addicts — looking for the best product, comparing brands, getting lured in by promises — are just as much a part. The branded bags occupy a niche created by gaps in the web of legal market relations, the criminalization of particular commodities, and the concurrent marginalization of populations. As Travis Wendel and Ric Curtis write in a 2000 study, “using and distributing [the stamps] has engendered a vibrant and complex underground world replete with signs, symbols and instruments that hold multiple layers of meaning and significance.”

In his 1967 book The Medium is the Massage, media theorist Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase “art is anything you can get away with” (which, ironically, is often attributed to Andy Warhol). Maybe we should consider the same sentiment to be true for the branding efforts laid out above: branding is anything you can get away with. Once you start to think about branding more expansively, you start to understand that we are constantly being sold something: billionaires brand themselves as philanthropists, drug dealers as saviors, artists as activists, and even a disease can be branded as a cure.

Various heroin bag stamps