#1: Shorthand

Technology has rapidly increased the pace of our day-to-day life. Our most mundane tasks have been analyzed and streamlined for the sake of efficiency, and our methods of communication are no exception. With the help of emojis, lols, and memes we’re able to say more than ever using less. But what gets lost in translation when speed becomes our only measure of success? Typography of Speed is a regular column by Felix Salut that explores past, present, and future examples of language accelerated by technology. More soon… ttyl!

Saccades

The image you see here is ‘saccades’—movements performed by the eye during the reading process. When reading, our eye groups letters and scans them in jumping movements in one direction. As the legibility of a text improves, our eye is able to group more letters at once, thus increasing the size of the saccade and allowing us to read more quickly.

As with many other typographers, I am interested in language and its visual representation. Over the years I have developed a special interest in attempts to make language more efficient by accelerating the reading and writing process. One of the reasons that I’m interested in the relationship between typography and speed is my mother.

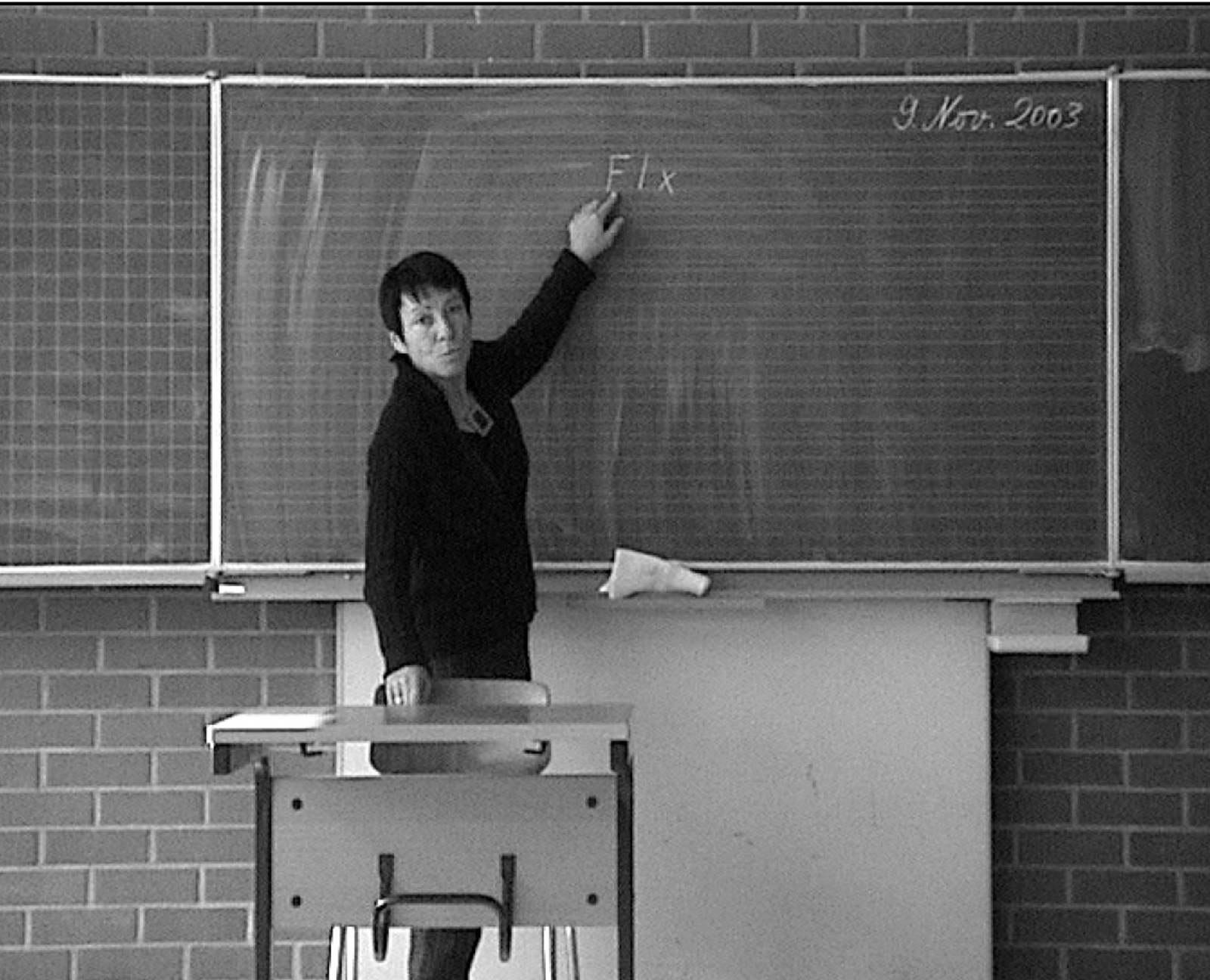

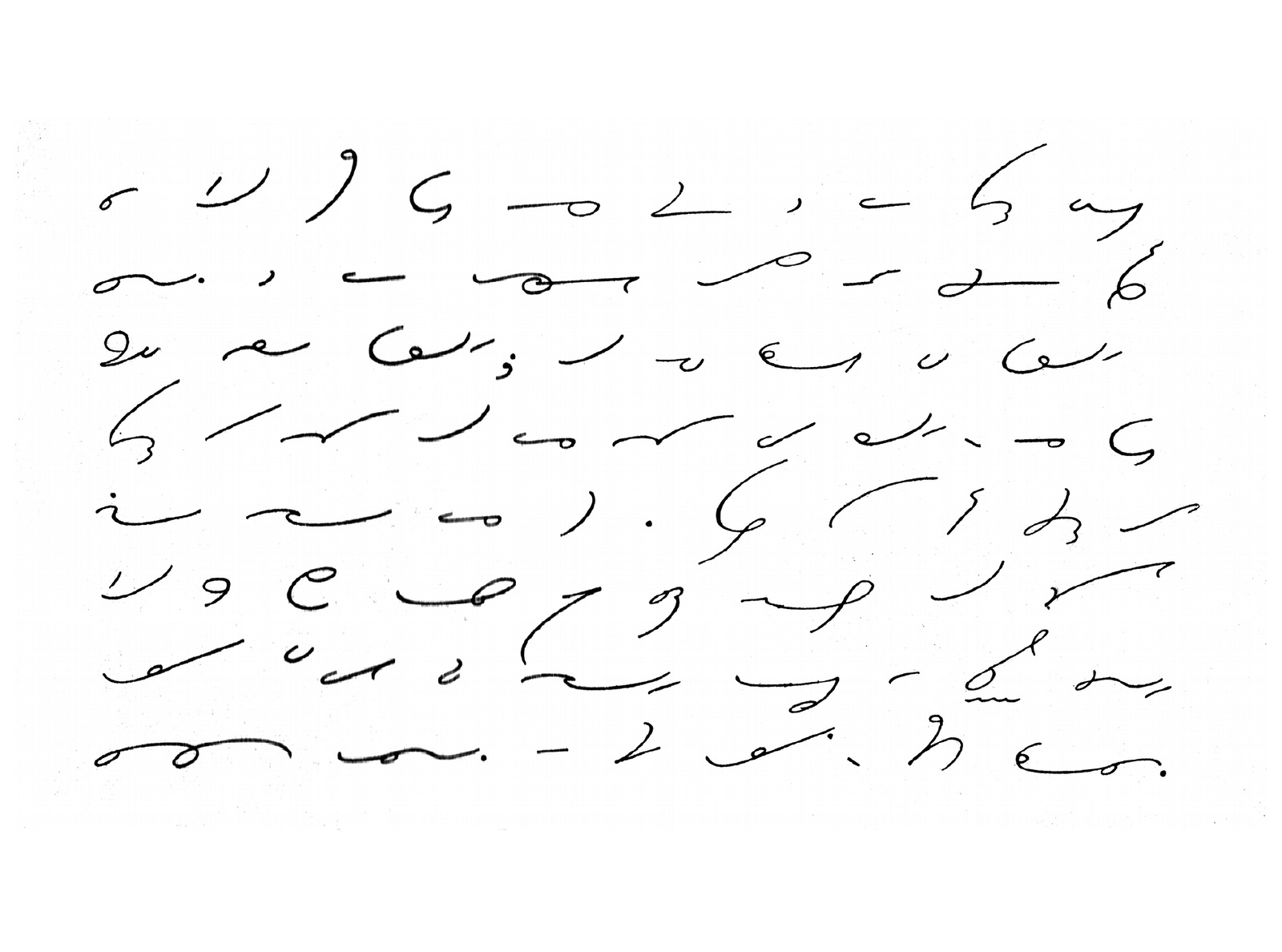

Still from film of my mother teaching shorthand

My mother not only has a quick mind, but she also used to work as a shorthand teacher. Shorthand is defined as a writing system that seeks to maximize speed and minimize the amount of writing. Years ago, I made a small documentary about my mother teaching shorthand. I was fascinated by her stenographic skills as well as the near-extinct nature of the writing system (my mother only uses it now in her diary as a kind of secret language). Despite the infrequency of its use, shorthand is a perfect example of an attempt to make language “faster.” Thus shorthand is the first subject of this column.

Why Was Shorthand Invented?

For centuries, cultures have been interested in accelerating the process of writing. The letters you are reading right now, for example, are the products of a desire to improve efficiency. Adrian Frutiger, in his book Signs and Symbols: Their Design and Meaning (1978) illustrates how the shapes of our letters developed out of a desire to reduce the amount of writing gestures needed to draw a letterform. He explains that the development of the lowercase ‘a’ goes together with a significant reduction of hand movements. If you look, for example, at the capital ‘A’ and compare it with the lowercase ‘a,’ it becomes clear that many more writing gestures are needed to form the capital. The development of our longhand (that is, our handwriting) is, therefore, a direct result of the wish for a faster writing speed.

Illustration from Adrian Frutiger’s Signs and Symbols: Their Design and Meaning (1978) demonstrating the stroke reduction from capital to lowercase letters

The relatively small improvement in the speed of longhand was only an initial attempt to improve the efficiency of writing. Shorthand systems that sought to further simplify letterforms have been in use for over 2000 years. Tiro, the personal assistant of Cicero, is often referred to as the father of shorthand having created one of the first shorthand systems in the Latin language. His method, mixing abbreviations of Latin letters, abstract symbols, and symbols borrowed from Greek shorthand, became the first standardized and widely adopted system of Latin shorthand with its own dictionary. The system was in use for over a thousand years until it became associated with witchcraft and magic and subsequently disappeared.

Tironian note glossary from the 8th century

A renewed interest in the linguistic system arose in the 15th century with the discovery that the writing system was being used in monasteries. Several Tironian symbols remain relevant today, particularly the Tironian ‘et’ used in Ireland and Scotland to mean ‘and.’

Saccads illustration from Gestalt und Funktion der Typografie (1983)

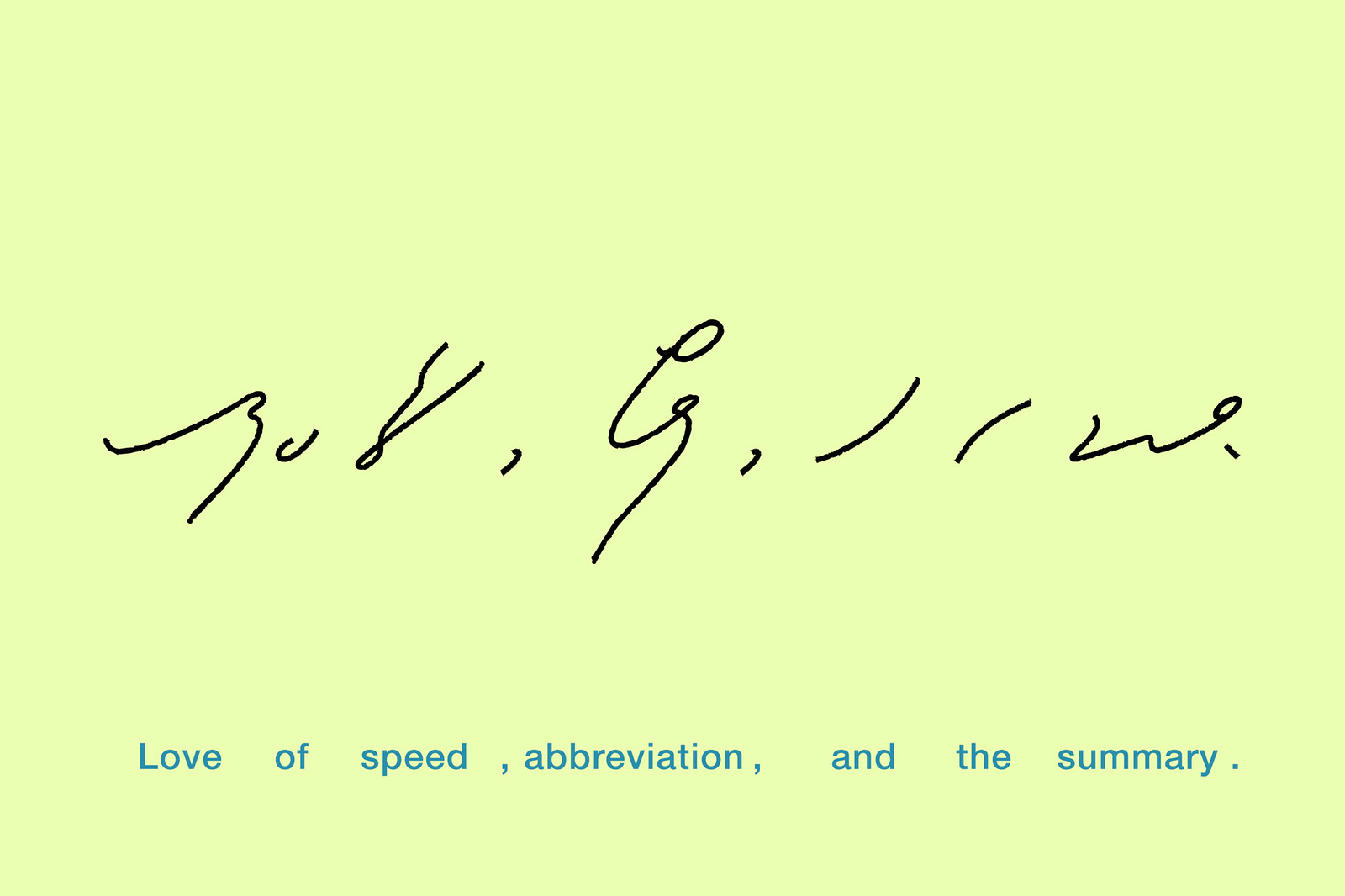

Quote from F.T. Marinetti’s Destruction of Syntax–Wireless Imagination–Words-in-Freedom (1913) written in Gregg Shorthand.

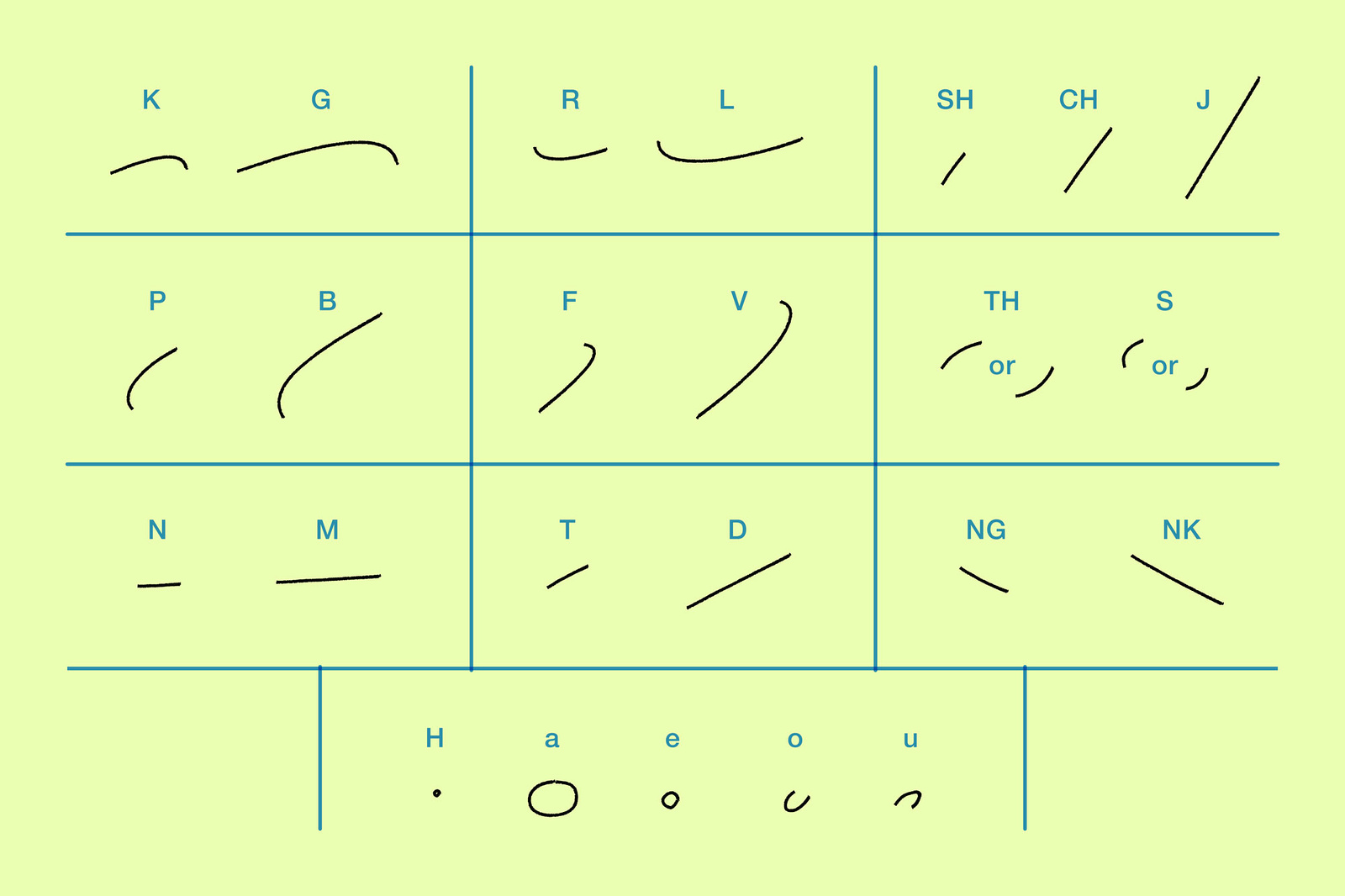

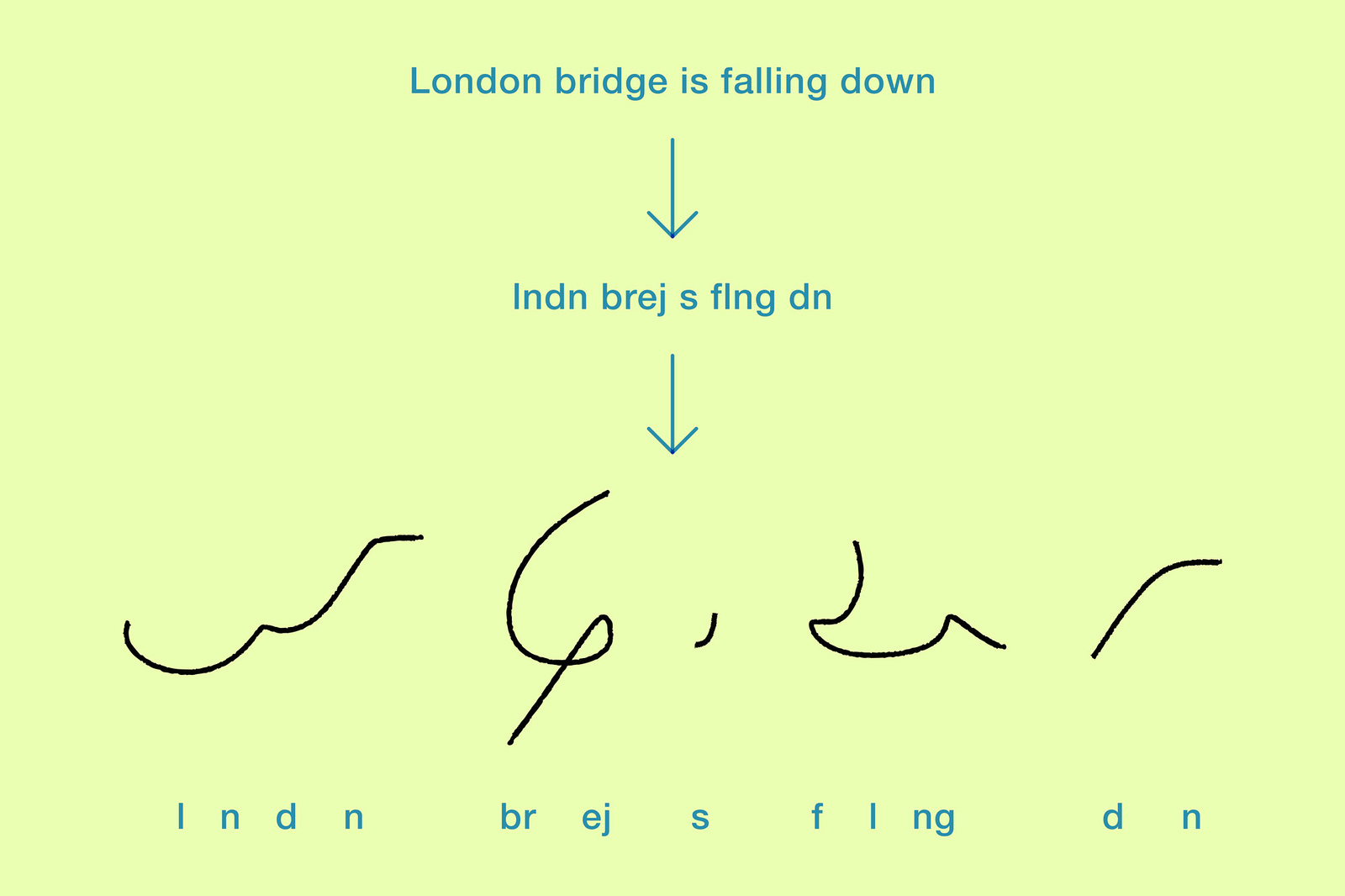

Examples from the Gregg Shorthand Alphabet

A sentence constructed using Gregg Shorthand

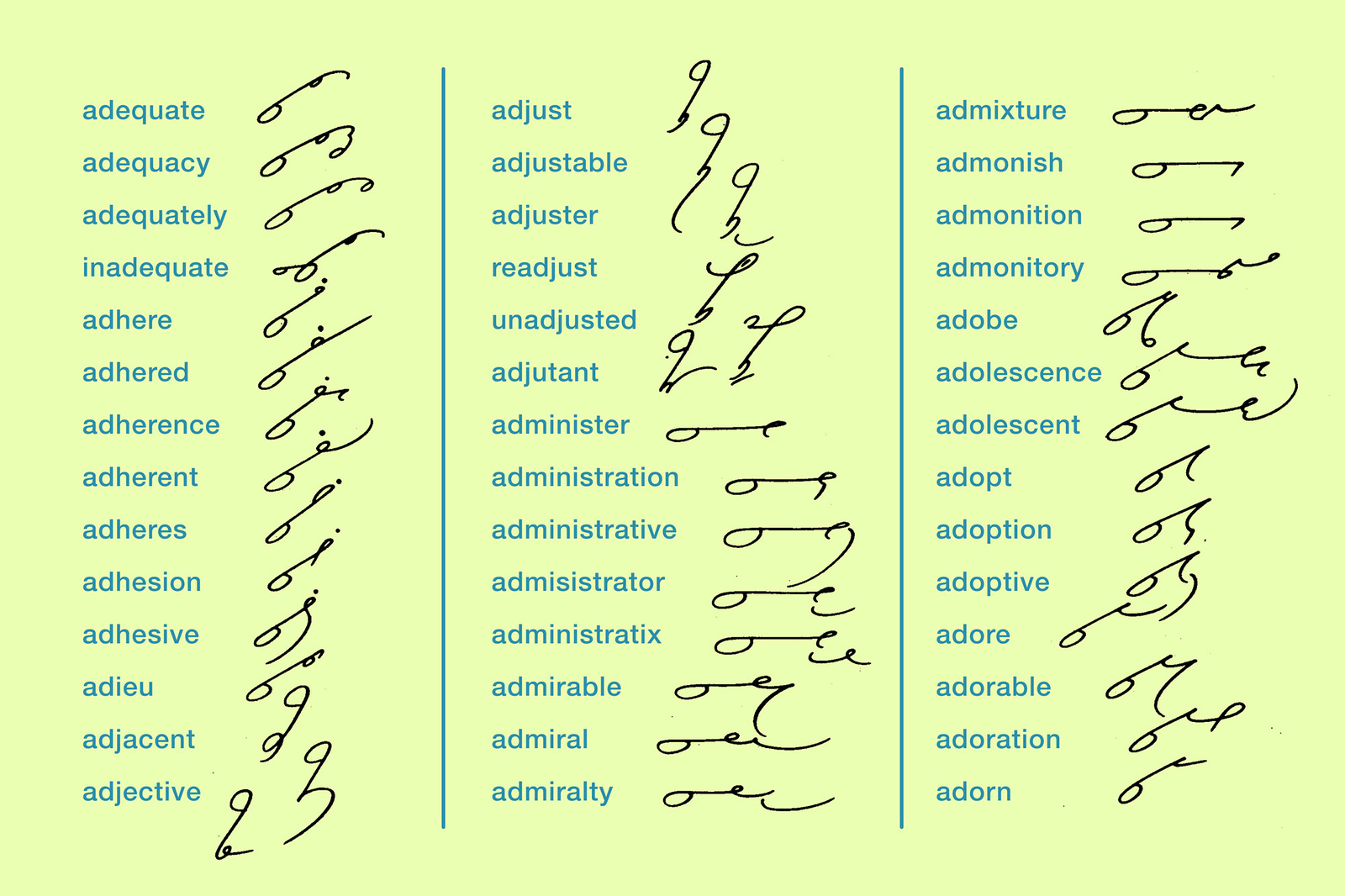

Translation examples from the Gregg Shorthand Dictionary

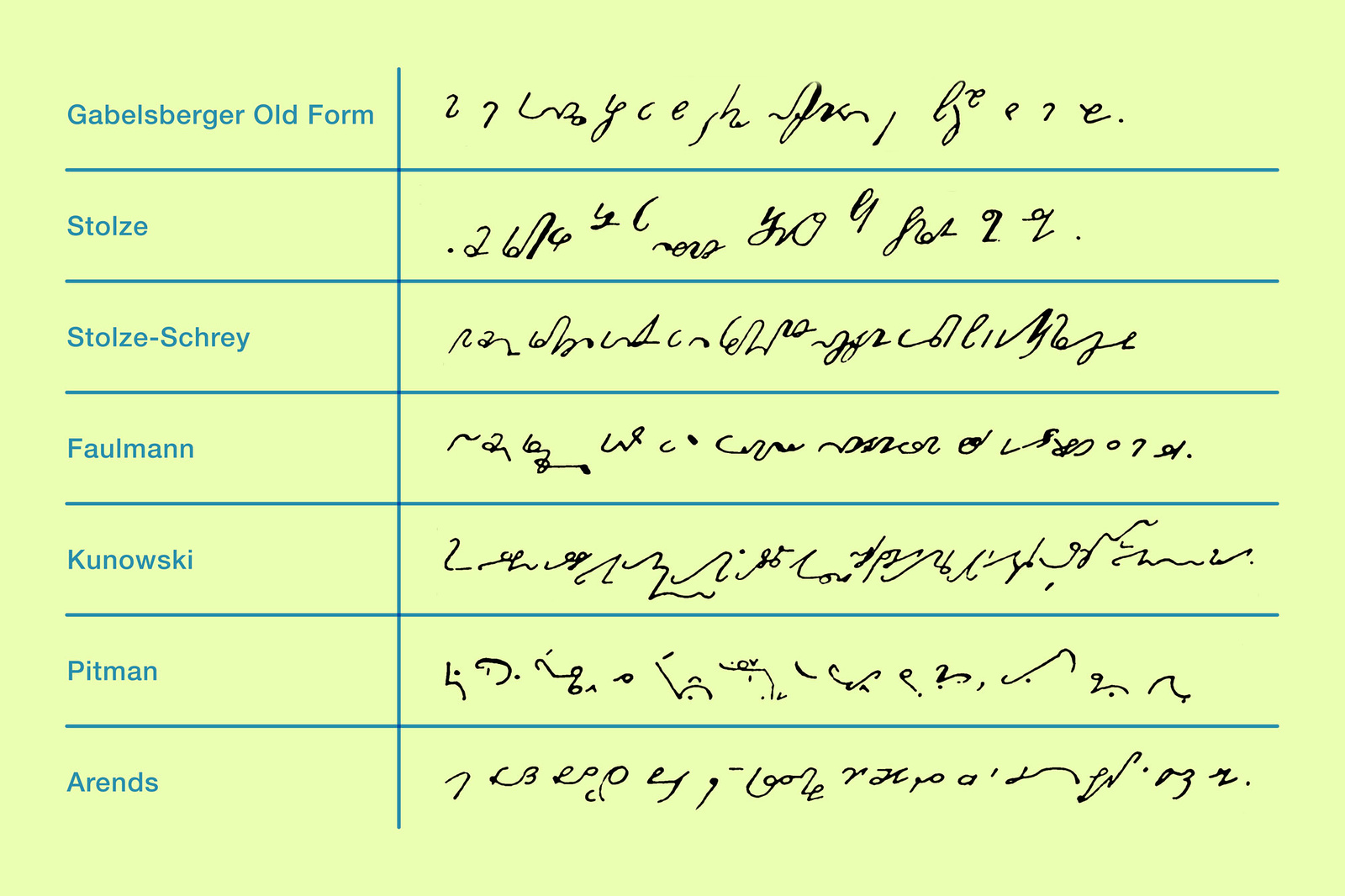

The same phrase (an advertisement for a German encyclopedia) written in various shorthand systems.

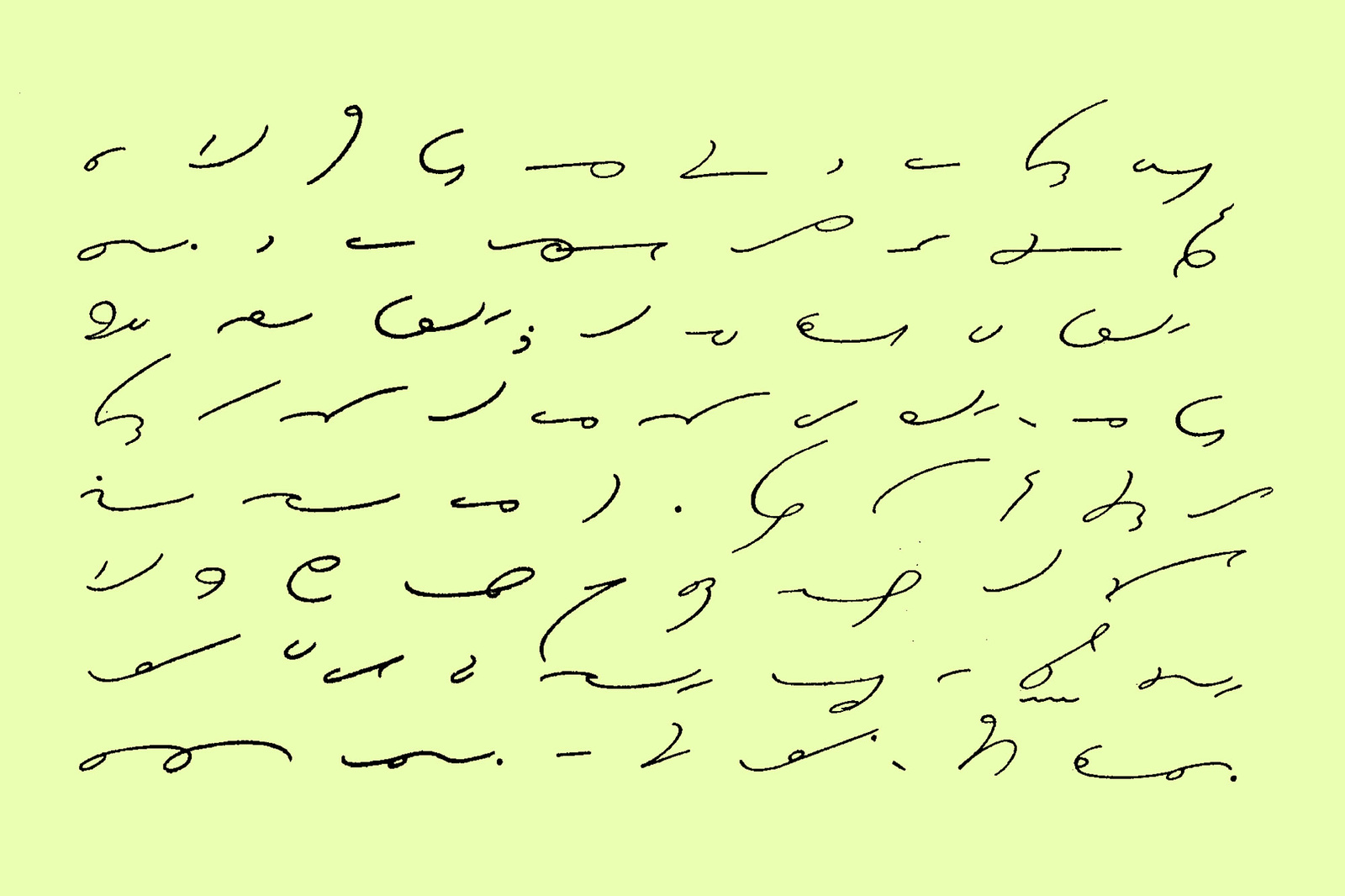

Gregg shorthand letter

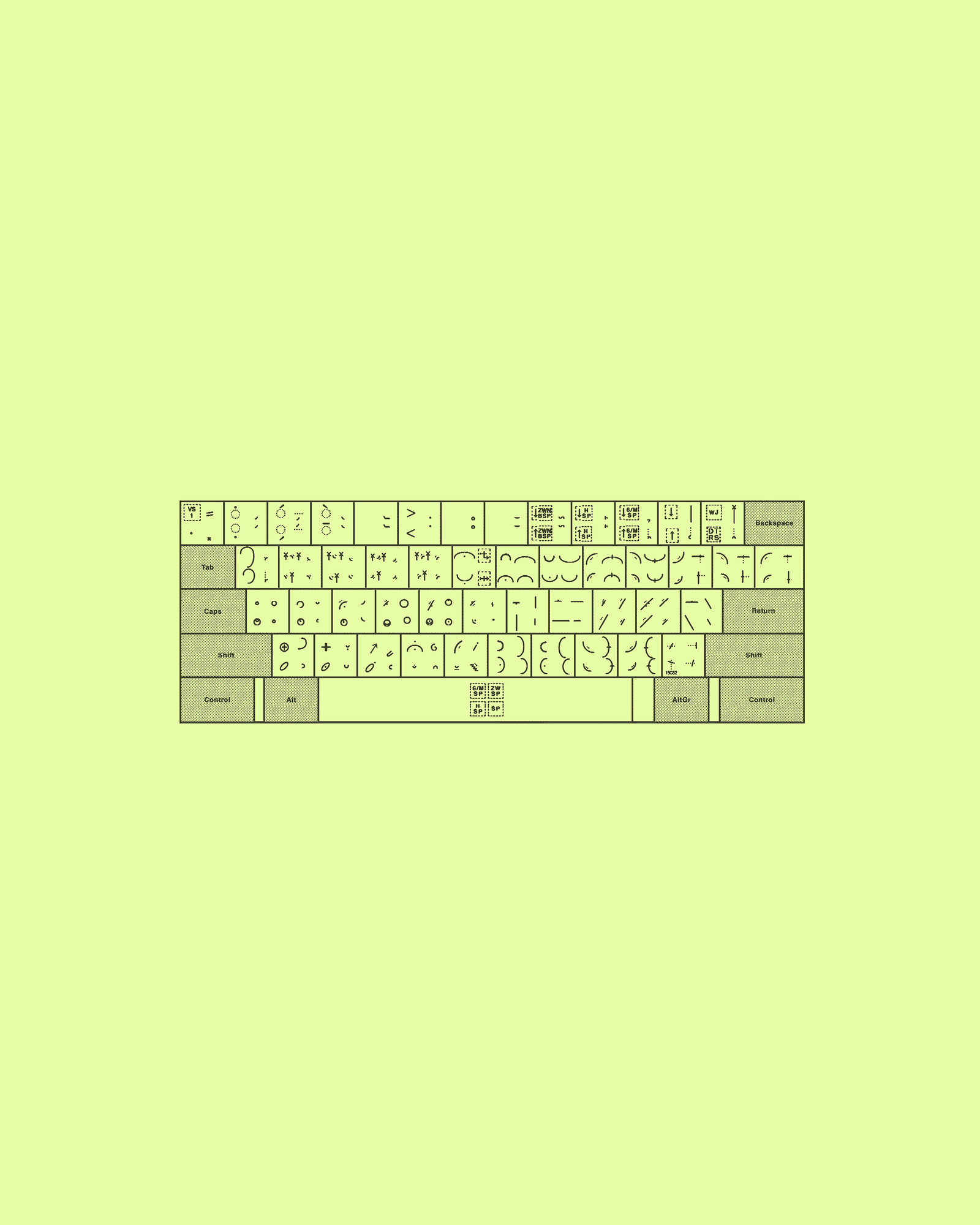

Keyscript

It is no coincidence that the further development of shorthand systems peaked in the 19th and early 20th century as the speed of language (and life) increased via newspapers, telephones, and radio. Devices used to store information, like film and the gramophone, were only invented at the close of the 19th Century and took decades to be made available as everyday tools. In these accelerated times with railway, cars, airplanes, and an inundation of information, society felt the need to develop faster notation tools.

“A loathing of curved lines, spirals, and the tourniquet. Love for the straight line and the tunnel. The habit of visual foreshortening and visual synthesis caused by the speed of trains and cars that look down on cities and countrysides. Dread of slowness, pettiness, analysis, and detailed explanations. Love of speed, abbreviation, and the summary. ‘Quick, give me the whole thing in two words!’”1F.T. Marientti, Destruction of Syntax–Wireless Imagination–Words-in-Freedom (1913)

A wide and varied range of shorthand systems have been developed in different cultures over time. Despite the many forms and techniques, each can be classified into one of two categories:

1. Stenographic Shorthand

Stenographic Shorthands substitute Latin letters with simplified or abstracted letterforms. The shapes of these letterforms can be further divided into two categories: geometric and script. In addition to new letterforms, this type of shorthand provides symbols and abbreviations for common words and phrases, which allow an individual well-trained in the system to write as quickly as a person speaks. My mother, for example, could write up to 200 words per minute using Stenographic Shorthand.

Example of Stenographic Shorthand

2. Alphabetic Shorthand

Alphabetic Shorthands use Latin letters but provide a logic for how words can be abbreviated. This generally entails leaving out vowels along with a grammar-based logic on how to shorten words (‘text’ becomes ‘txt,’ ‘thanks‘ becomes ‘thx’). Such systems include Speedwriting, Dutton’s Speedwords, Stenoscript, and Forkner Shorthand. Several systems supplement alphabetic characters with punctuation marks as additional characters. (For example, easy becomes ‘e-z’). A particular advantage of alphabetic shorthand that was not considered at the time of its invention is its ability to be used on a computer or cell phone.

Example of Alphabetic Shorthand

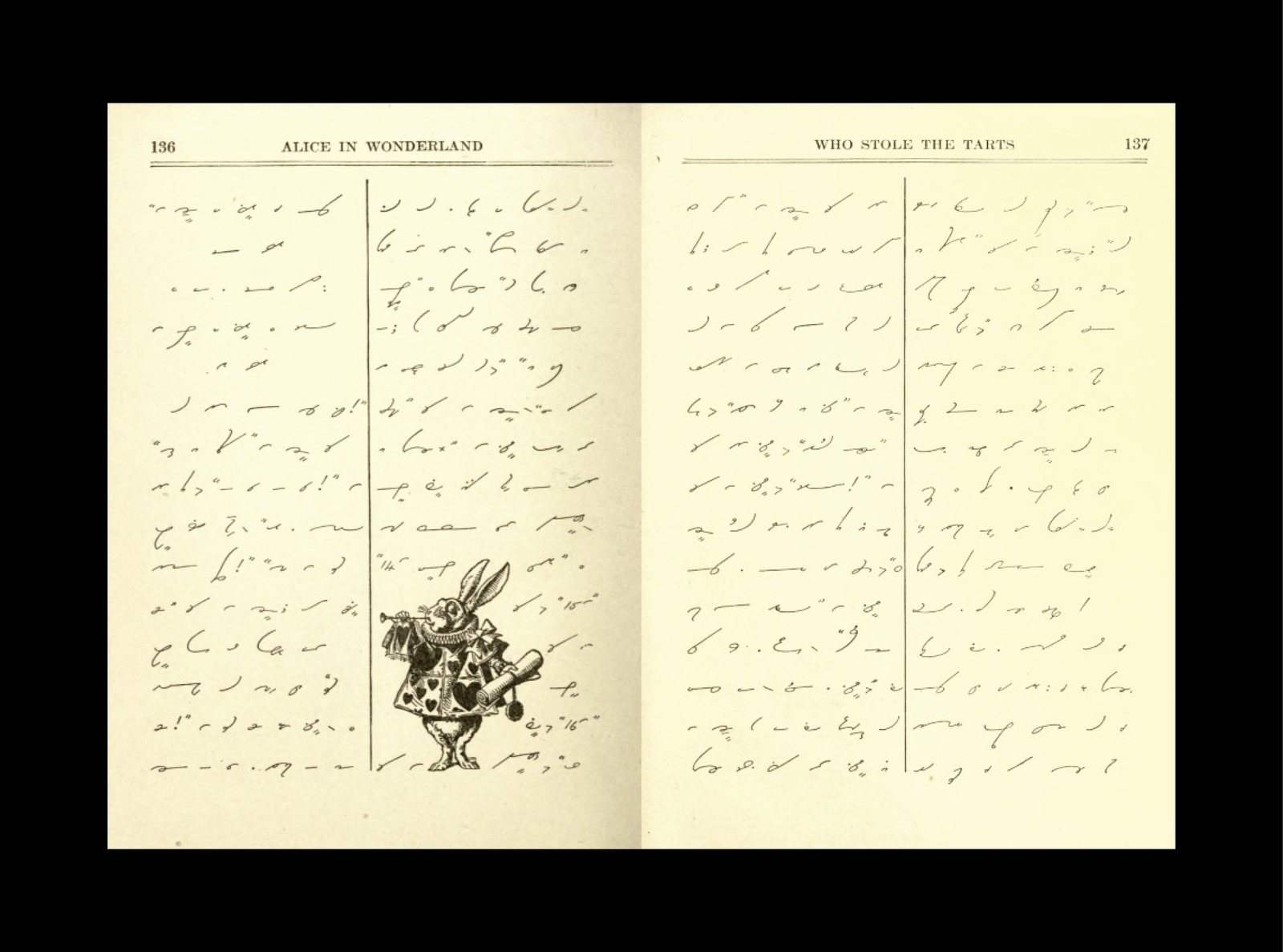

Alice in Wonderland written in Shorthand (c. 1919)

Stenographic shorthand systems have less and less function today, and mostly seem to end up in diaries like my mother’s. Principles of alphabetic shorthand, however, have made their way more and more into our common language via the keyboards of our telephones and computers. Its main principles are familiar to all of us today and form our everyday language.

In The History of Communication Media media theorist Friedrich Kittler claims that “new media do not make old media obsolete; they assign them other places in the system.” He explains how the invention of printing increased the value of handwriting because more and more people learned reading and writing.

I observe a similar phenomenon with alphabetic shorthand. The high-speed frequency of messages sent over 4G from one person to another via e-mail, text message, and apps have created a new channel for the principle ideas of alphabetic shorthand: vowels are left out and short forms are created for frequently used words. We all feel the need to type faster, with brevity, and with more efficiency on the keyboards of our telephones and computers.

My mother just wrote to me that I should have a closer look at the speed writing invented by Emma Dearborn in 1924. She says she was a woman ahead of her time. My mom says it’s like going back to the future.

Speedwriting Ad from Popular Science Monthly (1924)