#2: The Art of Indirection

Steganography is the practice of embedding secret messages within openly accessible information systems. For centuries the tactic has been used by underrepresented communities as a tool for protection, survival, and resistance in the face of oppression. Today, in an age of permanent surveillance, steganography remains a powerful strategy for groups looking to subvert inequitable structures of power and exploitation. In the ongoing column Dark Cousin, artist and designer Amy Suo Wu offers embodied reflection into the evasive territory of the visible and invisible, and takes us down a meandering path of coded language throughout history.

In the tradition of my mother’s culture, Chinese landscape paintings were often used by ‘scholar-officials’ to express opinions that included subtle political criticism. When scholar-officials were banished or removed from office, they sometimes resorted to painting to ventilate. However, even when shrouded in symbolic language, those opinions could induce punishment as they did for Su Shi, an eleventh-century official who was almost executed for writing poems that were regarded as defiant.

Su Shi, Wood and Rock (1037-1101).

As a result, the scholars sharpened their finesse and became very skillful in the art of indirection. For example, the scholar-official Zhao Mengfu painted an image of a groom and horse. In the early Yuan period of China (1271–1368), the ability to judge horses was analogous to the ability to recruit talented men as government officials. When an emperor fails to properly value his officials, one can express it as a failure to make good use of the horse. As such, Zhao’s paintings may be interpreted as a critique of rulers, suggesting that they take better notice of the talents of their officials and make good use of them in the government. The painting’s message indirectly attempts to remind emperors to properly value their officials.

This can be considered an example of steganography, a form of secret writing hidden in plain sight, otherwise known as the practice of camouflaged communication. At foremost, we can see how the horse is used as an object of veiled critique, benign on first impression until the analogy is unveiled. Technically, within the world of steganography, this would be called a visual semagram, the use of signs or symbols on innocent-looking or everyday physical objects to hide messages, in this case, a painting about horses.

My mother and I have always communicated obliquely. When I was a child she would wrap important lessons in extraordinary and captivating tales in the same way that deceptively shrewd parents trick young children of varying degrees of blindness to eat pureed vegetables by using lamb chops and whipped cream as its steganographic cover.

Using a porkchop as a steganographic cover to get a baby to eat vegetables.

As I grew older, her fanciful fables and parables turned into long-winded anecdotes concealing her heart’s message within, which left me suspicious as to why she couldn’t just tell me exactly what she was trying to say without the bells and whistles. Through the lens of Western psychological vocabulary, some would call this passive-aggression, innocuous banter that indirectly displays negative feelings instead of openly addressing them. To cope with the lack of clarity and certainty, I developed a hyper-vigilance at reading in-between the lines. Sometimes I was correct, but mostly I was tragically incorrect, misconstruing the complex situation with limited oversight. On the flip side, she would interpret my directness as disrespectful and brutish. But apart from the (in)directness, there were other factors that obscured our path to understanding each other. We were living with the painful ruptures of language, world-views, shadows of a broken family, and different generational struggles of migrant life. Unbeknownst to us at that time was the fact that we didn’t practise nor abide by the same linguistic, social, cultural, or emotional codes.

Grooms and Horses, Zhao Mengfu, Zhao Yong, Zhao Lin (1269, 1359)

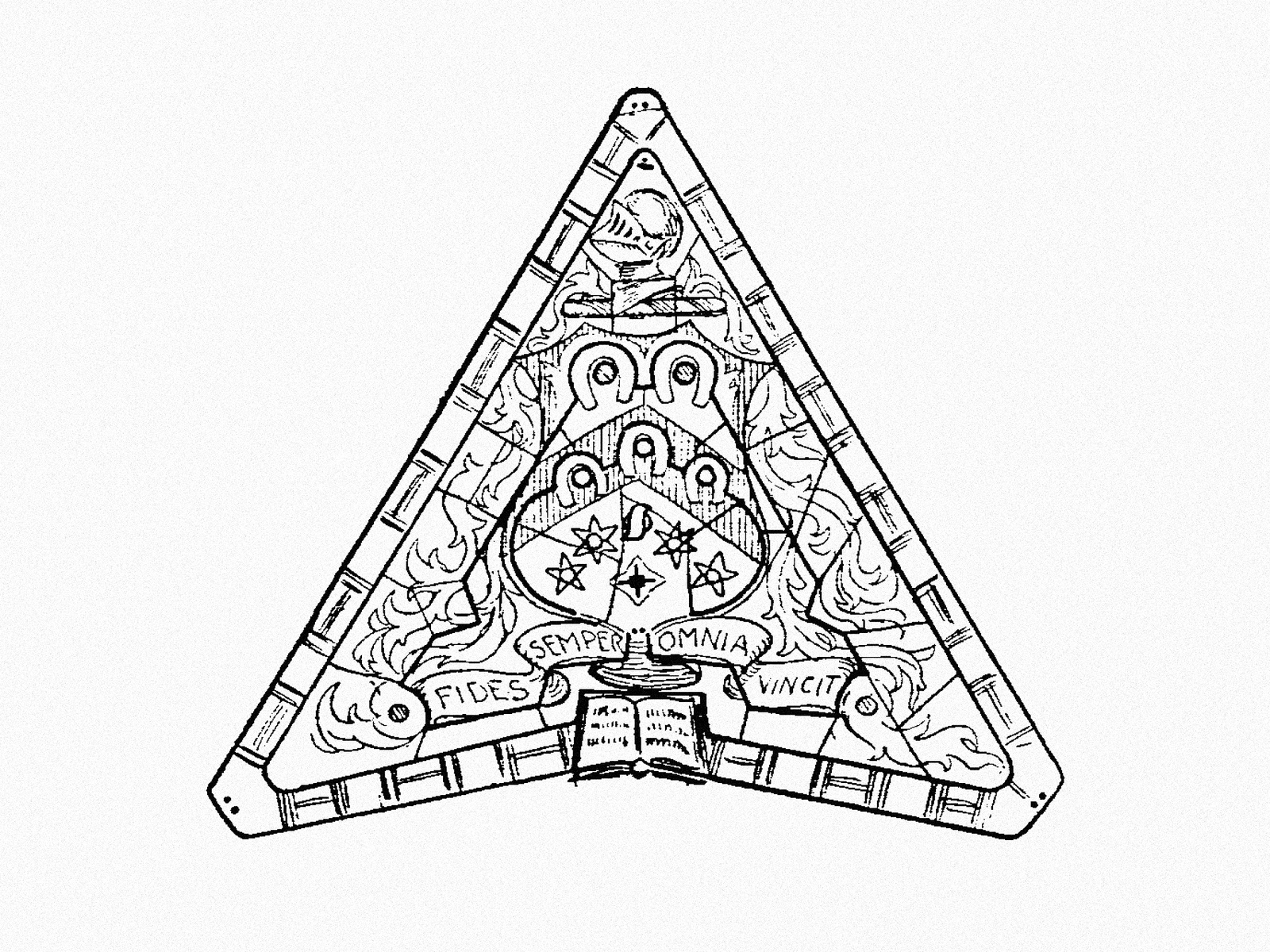

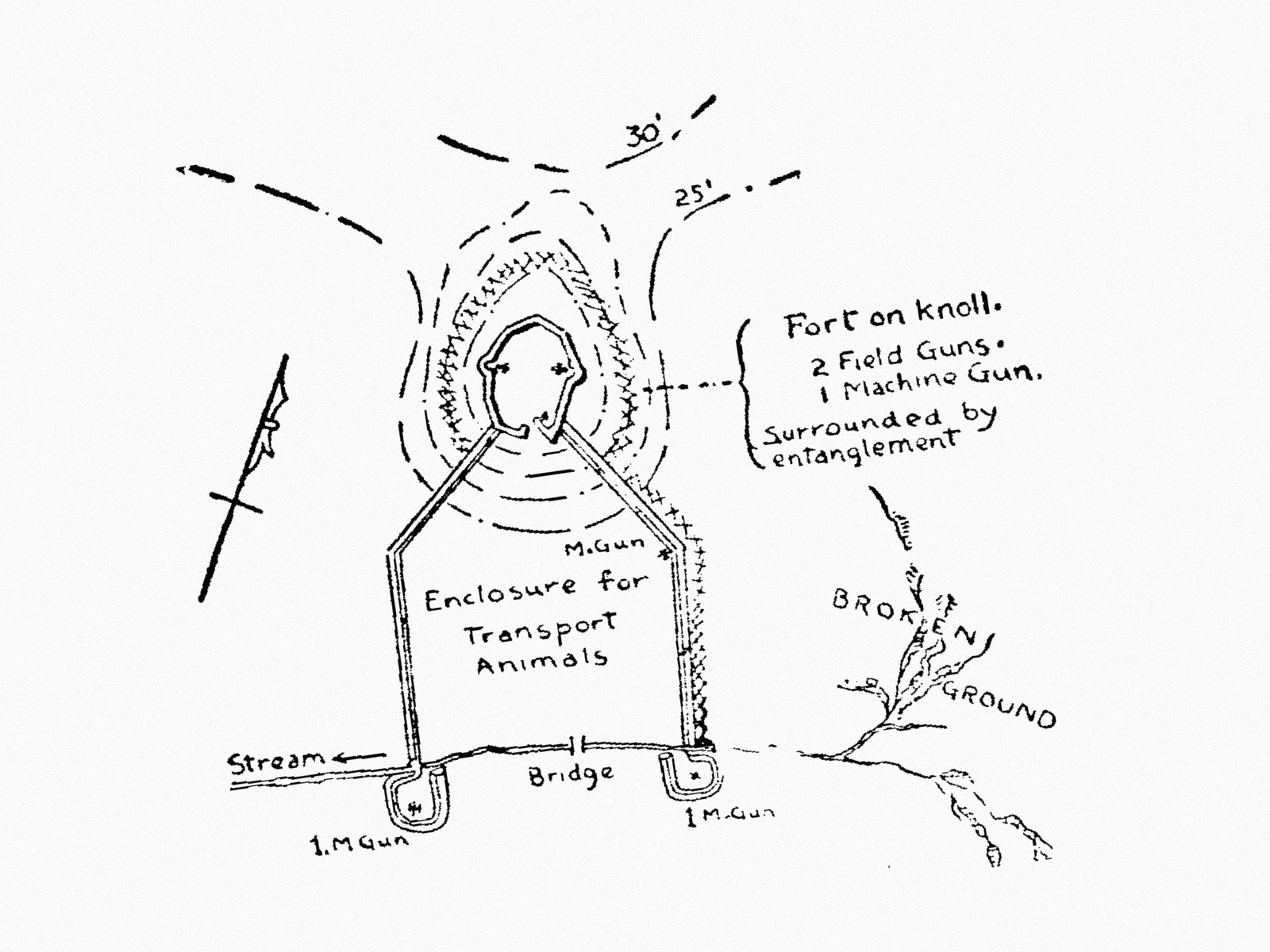

A sketch of a stained glass window is used as a visual semagram. The drawing uses particular symbols to define the size and position of weapons. Drawing by Robert Baden-Powell.

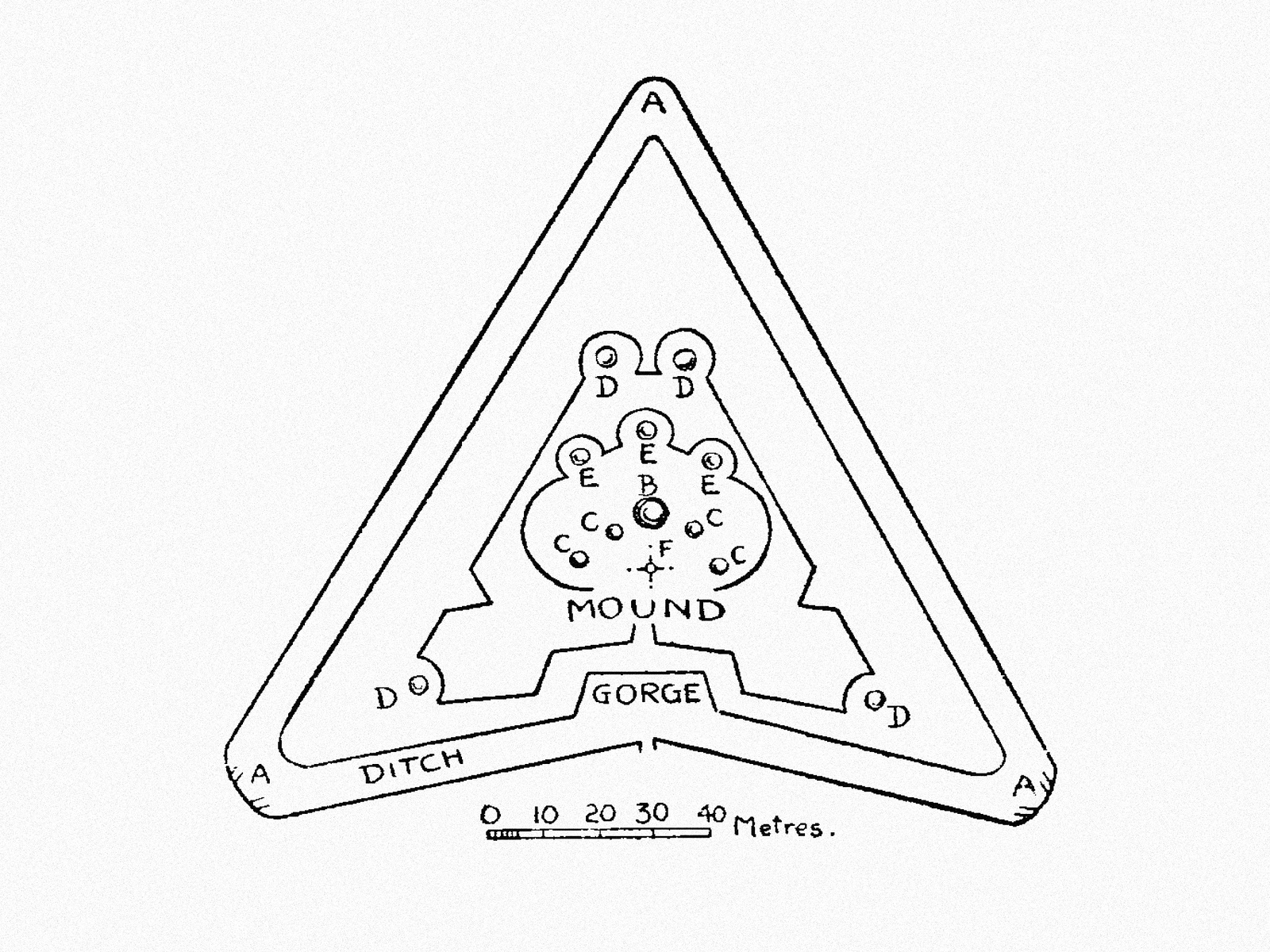

The plans of a fort concealed by the stain glass window sketch. Drawing by Robert Baden-Powell.

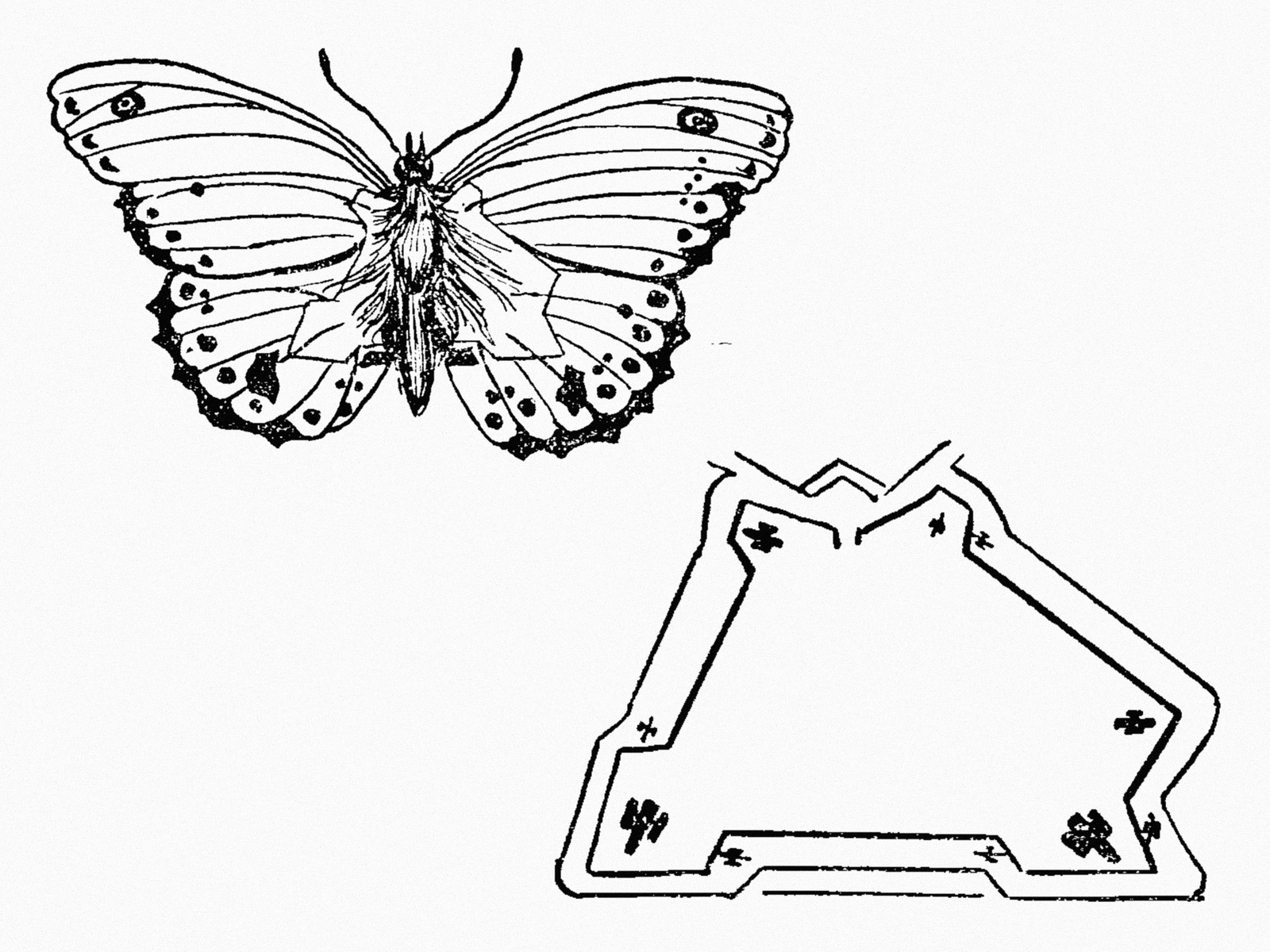

Similar to the stained glass window, the butterfly sketch is used as a visual semagram to communicate the accompanying fort illustration. Drawing by Robert Baden-Powell.

A sketch of a moth used as a visual semagram to communicate the plans of a fort. Accompanying the illustration was the text “Head of Dula moth as seen through a magnifying glass. Caught 19.5.12. Magnified about six times size of life.” The text added further detail, hiding the scale of the map, 6 inches to the mile. Drawing by Robert Baden-Powell.

Fort plans revealed by previous sketch of a moth head. Drawing by Robert Baden-Powell.

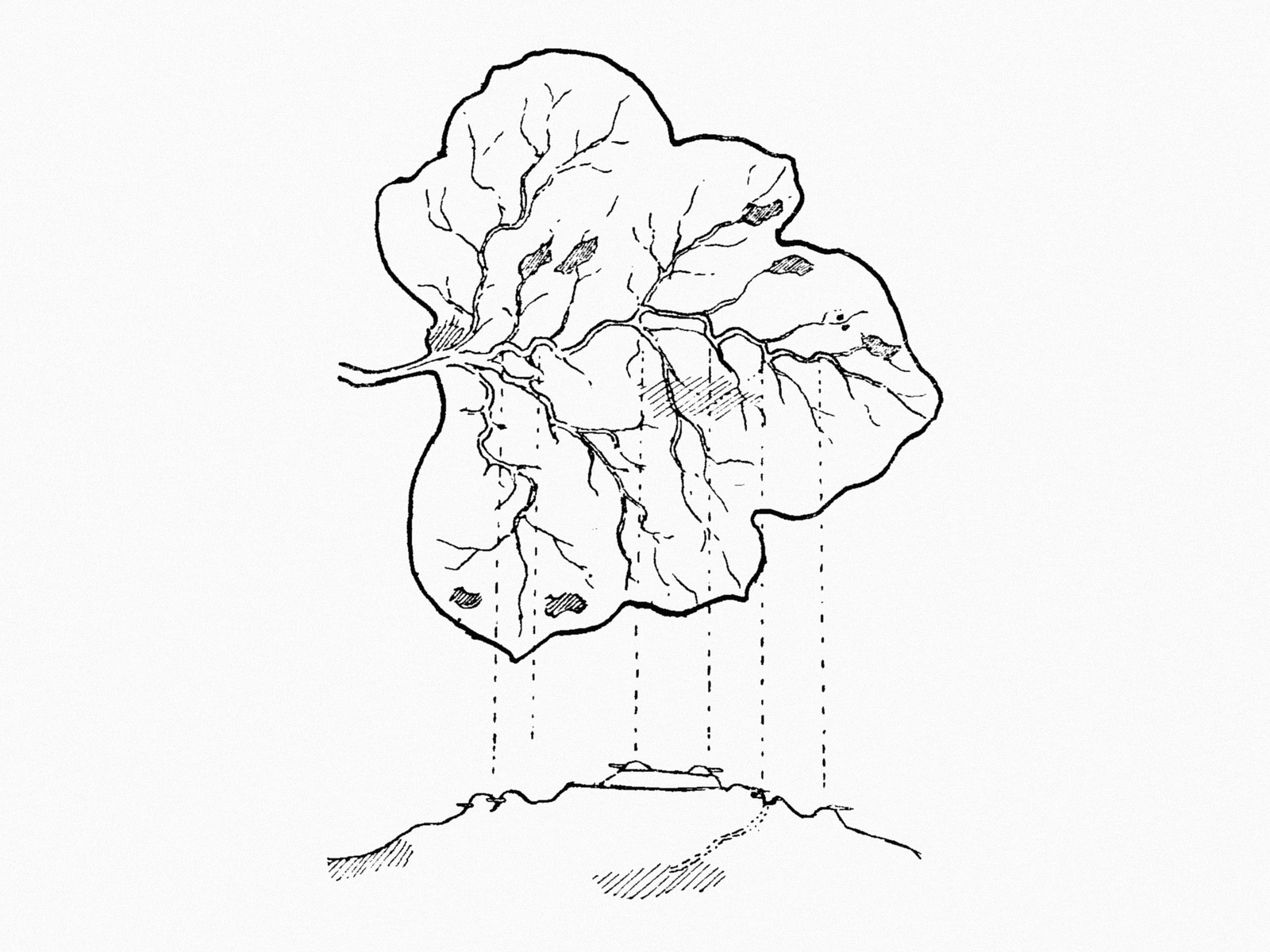

Here, the drawing of the leaf acts as a visual semagram where the veins on the plant signal the outline of a fort. Drawing by Robert Baden-Powell.

Growing up as an immigrant child in the Western suburbs of Sydney, I felt neither understood by the people who traversed through my domestic sphere nor the public sphere. That is why being understood and seen back then ultimately felt like a matter of life and death because what was at risk was the lifeline of connection, a flimsy thread of survival. It is no wonder I developed an aesthetic preference for a certain style of communication that is clear, simple, and direct. I found this to be practical and effective after I migrated to the Lowlands, a place with a culture known to be brutally and unflinchingly honest. Although sometimes controversial, at the time it felt like an unburdening of the soul to know exactly how people felt without the mental games and acrobatics that I would otherwise ceaselessly perform trying to figure out what hidden feelings people harboured but couldn’t for whatever reason tell me. It was like I could see the invisible lines and boundaries of a terrain for the first time. Even though I couldn’t speak its linguistic codes, I could make sense of its social and emotional codes, and with that, I could move around, and be brave enough to open up and make connections freely.

But after being in the Lowlands for 16 years, my English has inevitably mutated into a lopsided outgrowth of continental European Dutch English with vestiges of a faraway Australian accent. Whenever I happen to be in a conversation with any native English speaker, but especially with a native Australian English speaker, I become cripplingly conscious of how bastardised my English has become. Routinely, I leave my body and hover over it watching as my poor mouth struggles to make improvised sounds masquerading as intentional sentences. Only recently have I begun to entertain what I have come to understand as my ‘simple bastard’ style of voice as a richness rather than a lack and embrace the odd flavours of my mutation as its own aesthetic condition that tells the story of where my body has travelled and the particular ways I’ve navigated treacherous entanglements of communication.

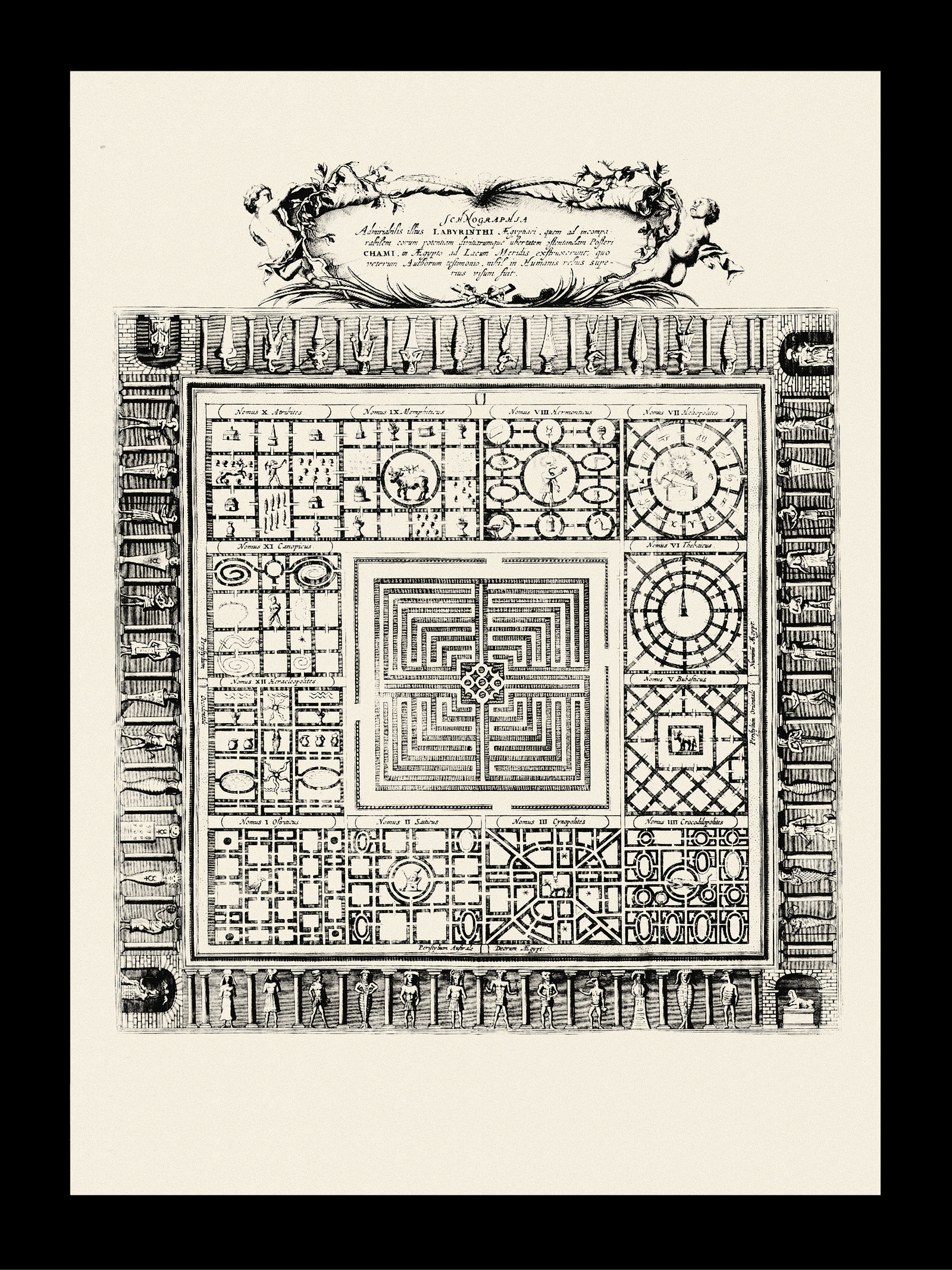

In the encyclopaedic work Naturalis Historia published in AD 77, the Roman scholar, Pliny the Elder1In another chapter, Pliny writes about how to use the milky juices of the tithymalus plant as invisible ink for communicating with illicit lovers describes mazes as enclosing ‘circuitous passages, windings, and inextricable galleries which lead to and fro.’ It is as if my mother has created mazes with multiple channels built around her that deliberately veer away and obfuscates interlocutors from the heart of the matter. Like steganography, she has concealed her true intentions and guards it through a series of illusionary trails that lead astray. It is protection through confusion, much like other principles of steganography; disguise, abstraction, masking, camouflage and mimicry. Allegedly, the oldest known mazes are Egyptian built in the 19th century BC to guard the tomb of Pharaoh Amenemhat III against looters through intricate architectural subterfuge. Pliny continues and invites the reader to ‘picture [to] ourselves a building filled with numerous doors, and galleries which continually mislead the visitor, bringing him back, after all his wanderings, to the spot from which he first set out.’ Mum reminds me that Chinese culture is rich with fighting strategies, warfare tactics, conspiracies, and schemes on how to please, manipulate, and deceit. She tells me that ancient Chinese philosophy on warfare values deception and ways to stop violence over direct confrontation.

I pressed on, ‘do you have to conceal yourself from me?’ She said no, but for her family members, it was a resounding yes. In the same way that my simple bastardness developed as a response to my environment, my mother’s labyrinthine agility has allowed her to eschew noxious familial relations and survive. They, too, tell a tale of where she’s orbited and the various entrapments she’s fled from. Being with her was a masterclass in learning how to tread as lightly as possible in an environment where relations and events are embroiled in ways that you cannot foresee and where trust is slowly built over time. My mother is the nimblest master of the art of conflict evasion and the most entertaining hustler you would never have guessed2The founder of the Boy Scouts organization, Robert Baden-Powell, in his 1915 DIY manual on spying titled My Adventures as a Spy, wrote a chapter on “The Value of Being Stupid” about how someone with the appearance of having nothing below the surface can be a huge advantage. For more about co-opting stereotypes, tune in for the next article.. In a heated conversation, she will jump on a horse and run through the maze until you are utterly dazzled, finding yourself exhausted and realising too late that she has long exited the compound. And in a flash, she’s evaded the blaze, slipping out into the distance.

Egyptian Labyrinth, Athanasius Kircher (1670)