All at Once

The process as we move our eyes from word to word is corrective and revisionary rather than progressive. Each new word revises the complex picture we had before. —Samuel R. Delany

To return to the opening pages of Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren is to meet Kid, the half-barefoot dyslexic poet-protagonist, on his way into the labyrinthine post-disaster zone of Bellona. To see that Kid’s memory has shattered, fragmented, and to sense that its linear orientation was always an illusion. To enter into a city ruin and slowly recollect the shards.

Delany spoke of his 1975 novel as a kind of study and exaggeration of a very American term: the inner-city, “… that burnt out section of your city where the general functions of urban life go on at a very depressed rate.”1Delany interviewed in John Akomfrah’s The Last Angel of History (London: Black Audio Film Collective, 1996), 27:50. In this city without authority, we see Kid’s hip gang member friends gather, party, cruise, fight, and generally flourish while the stubborn hangers-on to the old capitalist infrastructure appear miserable and delusional.

A number of science fictional events take place without any technological or physical explication we might expect from the genre: a single night of two moons, one long day with an enormous sun, rearranging city streets. We’re mostly reminded of the tradition in which we’re reading when we enter the character Tak Loufer’s apartment and find books by Delany’s sci-fi colleagues—Thomas M. Disch, Roger Zelazny, and Joanna Russ—buried within Tak’s library. Or when we pause to consider Delany’s narrative structure as suggestive of time travel by beginning the novel with the second half of a sentence, and then ending the novel with that sentence’s first half. It’s a circular time travel in which the characters can influence the goings-on in Bellona, but this influence, whether they realize it or not, is always in service of maintaining the novel’s loop.

Dhalgren’s looping point occurs on a bridge. It’s here that the reader is led to understand that with every loop the protagonist switches between male and female. At the “start,” Kid, walking alone on the bridge into Bellona, passes a band of women who question him about the outside world. By the “end,” Kid, walking among a band of men away from Bellona, passes a single woman on her way into the city, and questions her about the outside world. When we finally recognize the loop, are we already out of it? Is it possible to give away a loop’s ending?

Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren front cover (Des Plaines: Bantam Books, 1975).

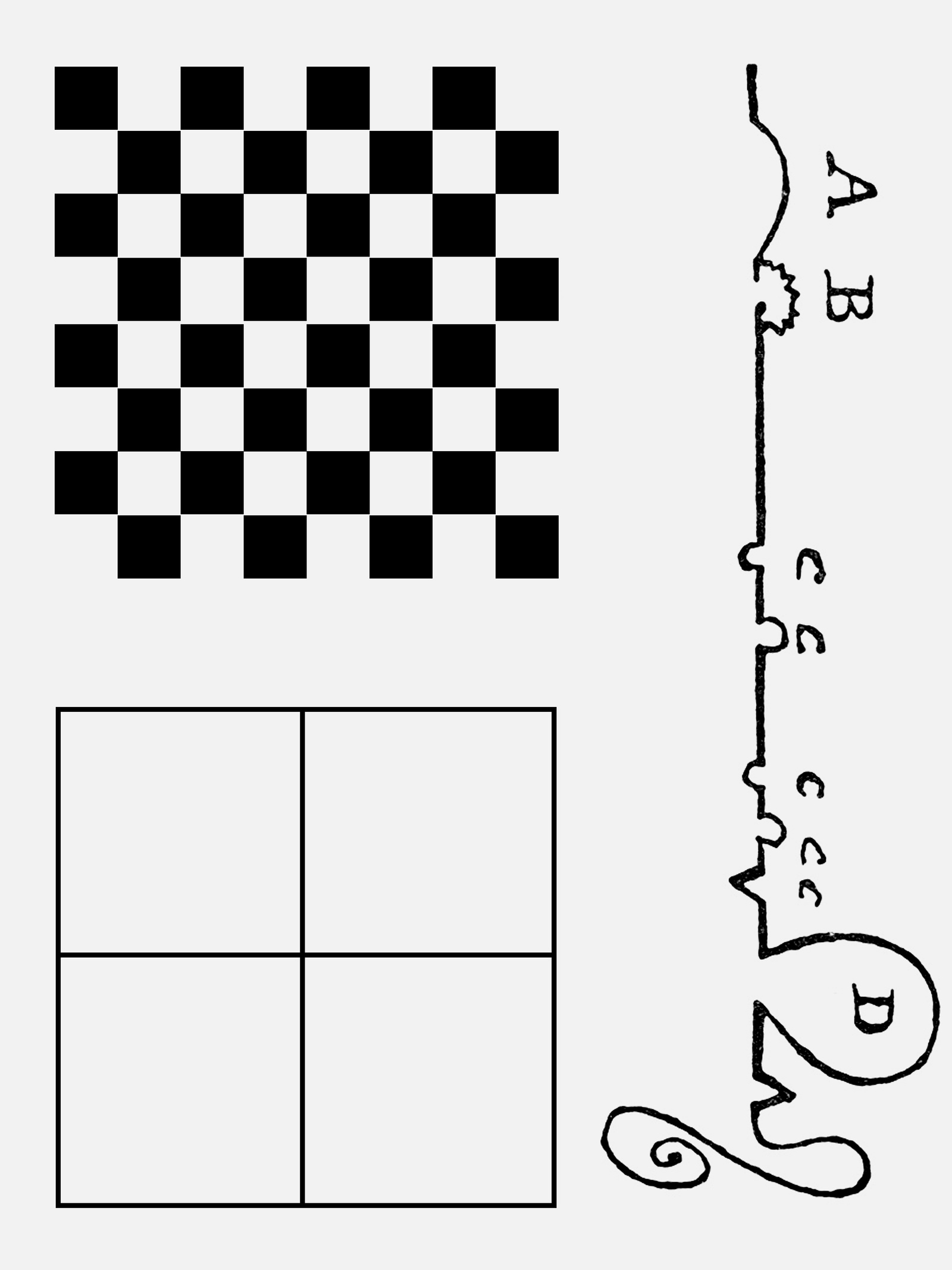

Delany was well aware of the literary tradition of using geometric metaphors to organize narrative, nodding in his personal writings from around this time to Lawrence Durrell’s four-coordinate quartet, Lewis Carroll’s fascination with chess, or Laurence Sterne’s digressive line drawings. As late as 1972, he considered publishing Dhalgren as two discrete volumes—volume one being titled Prism, Mirror, Lens and volume two being titled The Scorpion Garden—which were to be considered as two wings of a Möbius strip. A Möbius strip is an unorientable object, a two-sided strip twisted and connected at its ends to make one continuous surface. Delany theorized that a text based on such a strip might only be truly enjoyed the second time around, and that while one passes over the same space, one might now be on a different surface. By extension, one could read his novel in completion and then reenter the loop, thereby producing a new textual landscape on the second, third, or fourth pass. This two-volume structure never reached publication, but in its finished form he still considered Dhalgren to have an outer side and an inner side.

Early in the novel, Kid’s life in Bellona is propelled forward (or backward?) when he’s given a second-hand spiral notebook. We learn that this notebook’s previous owner has written throughout it, but only on its right-hand pages, and that it opens, word-for-word, with the first few sentences that open Dhalgren. The half-barefoot dyslexic poet-protagonist with a half-written-in notebook. While organizing the novel, Delany referred to its outer-ness and Kid’s notebook’s inner-ness. Kid uses the notebook’s blank left-hand pages to compose a collection of poems, one that eventually sees great popularity among Bellona residents—although when they discover that the notebook had a previous owner, they call his own poetic authorship into question. There’s little mention of the substance of these poems, but we know that the poetry collection, titled Brass Orchids, has, as its illustrations, photographs of Bellona printed in black ink on black paper. Imagine holding these illustrations up to a light source and viewing them from the side such that the ink reflects the light to make the photographs visible to the eye.

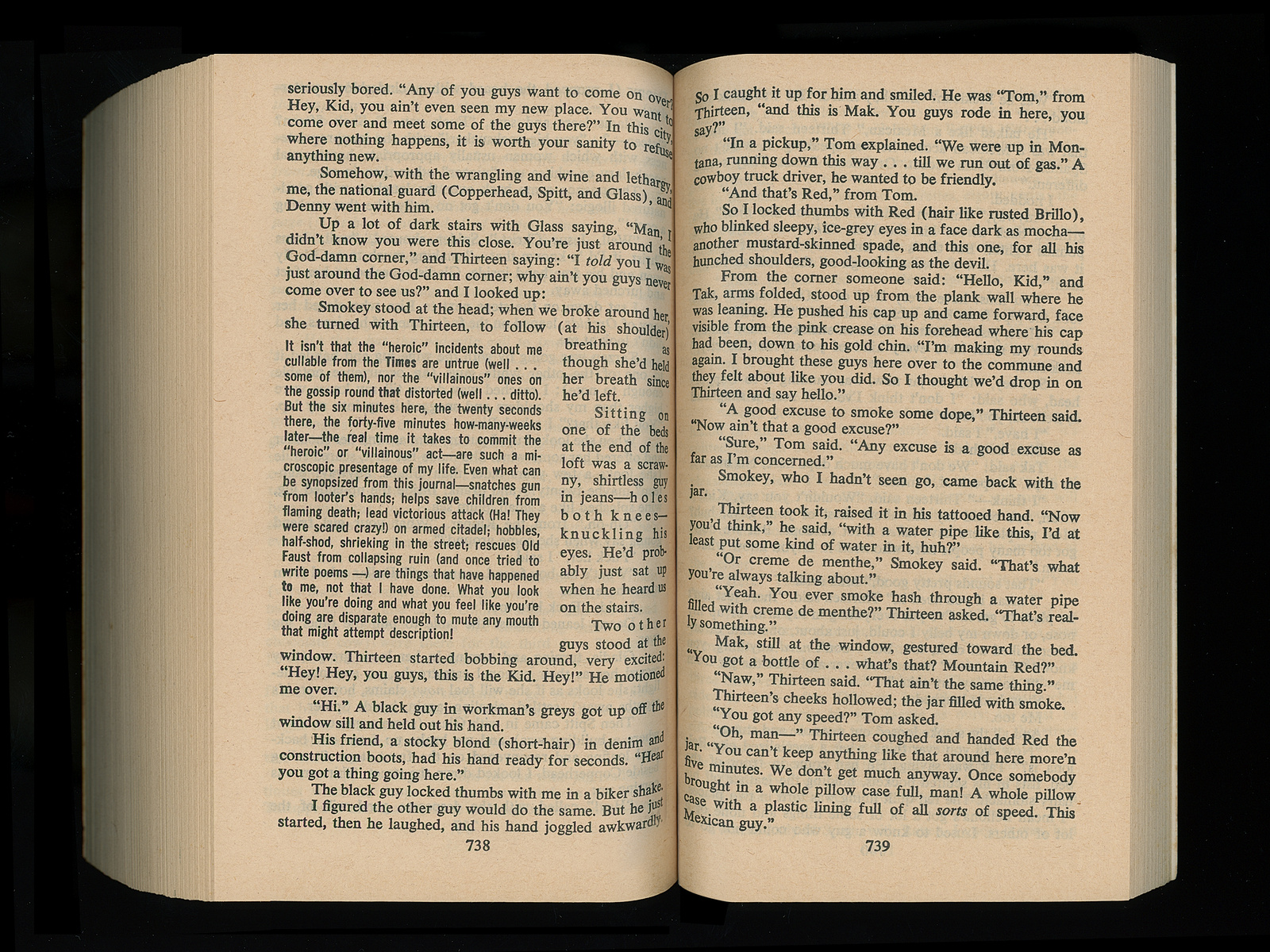

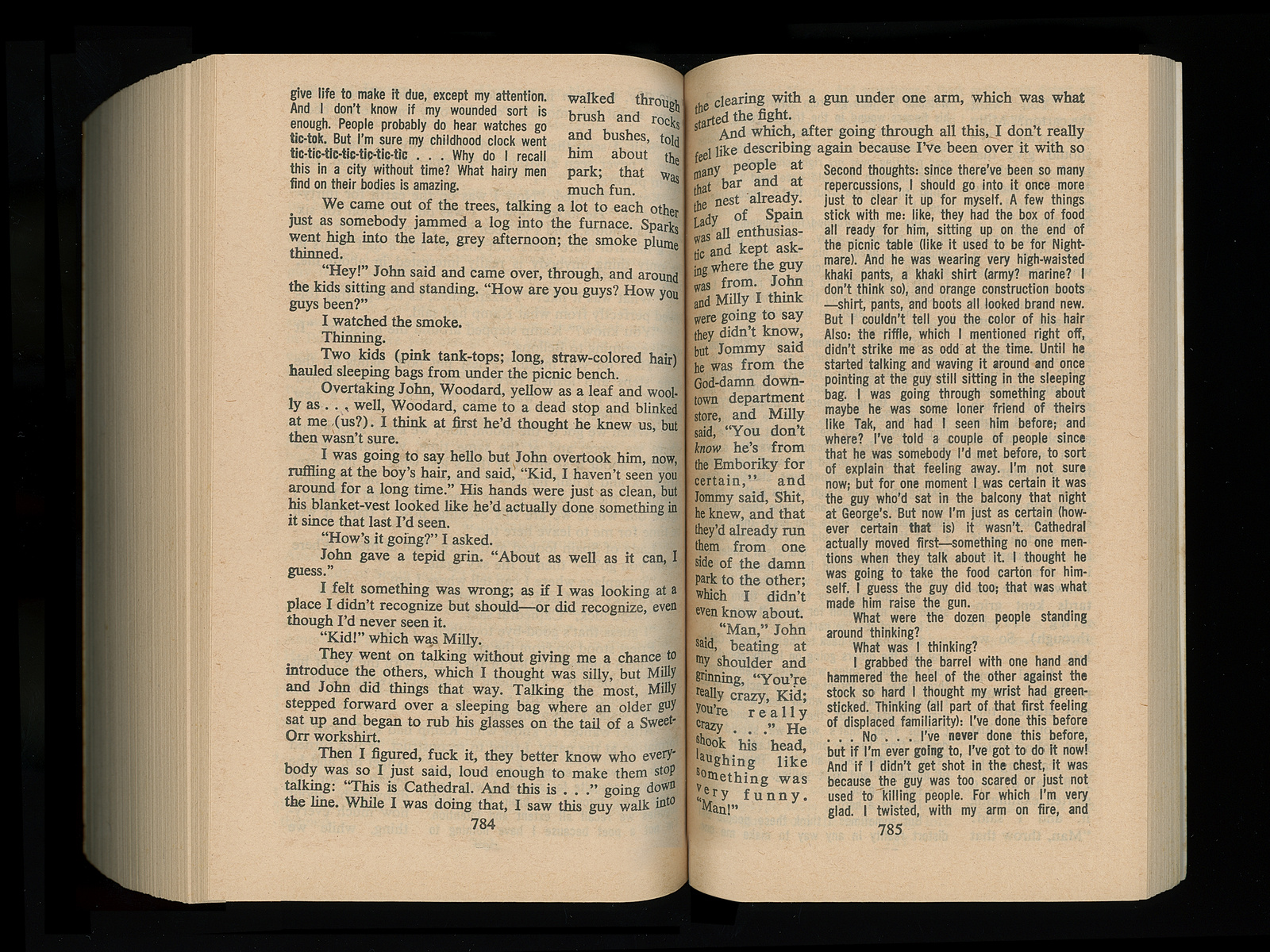

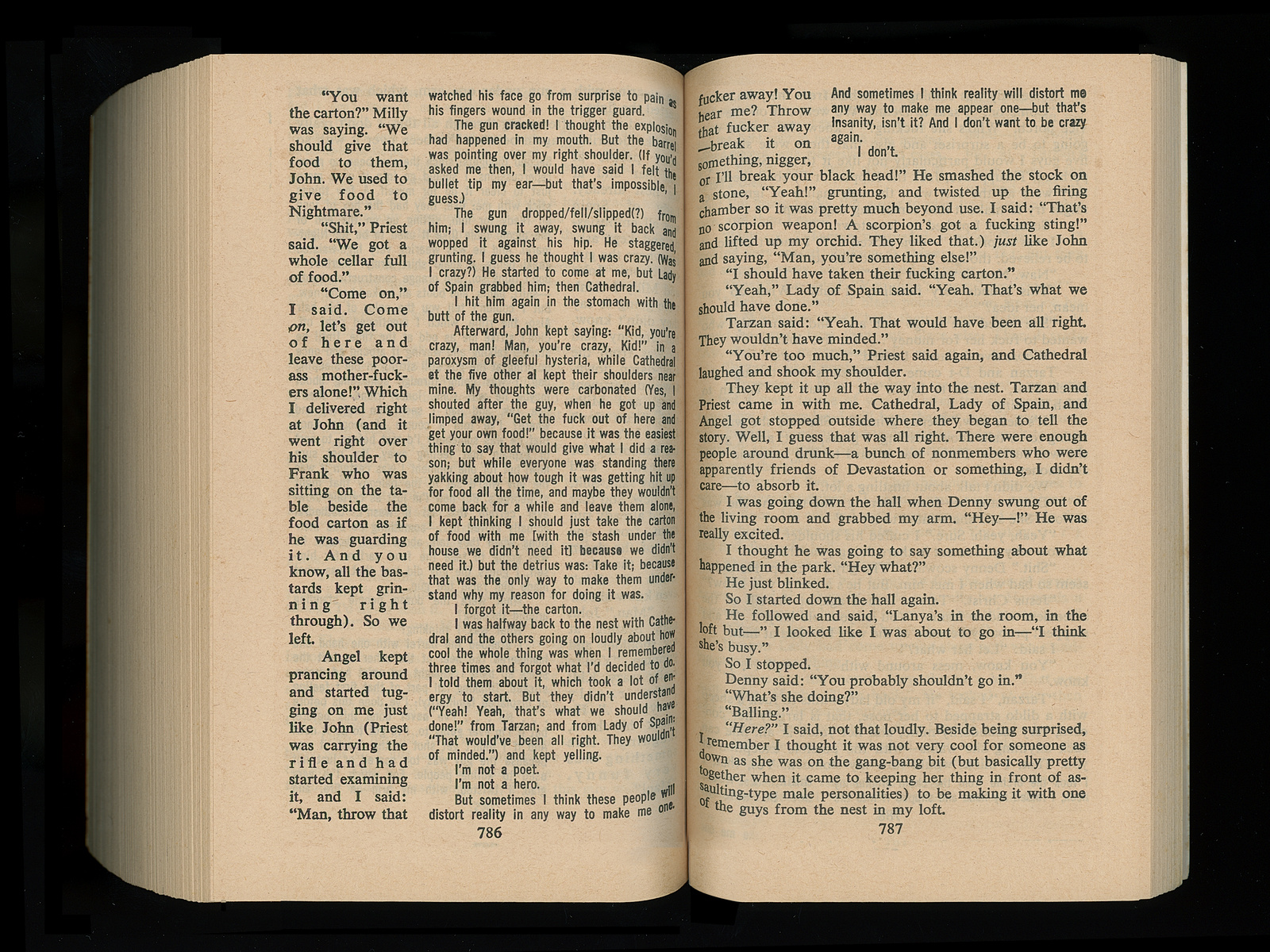

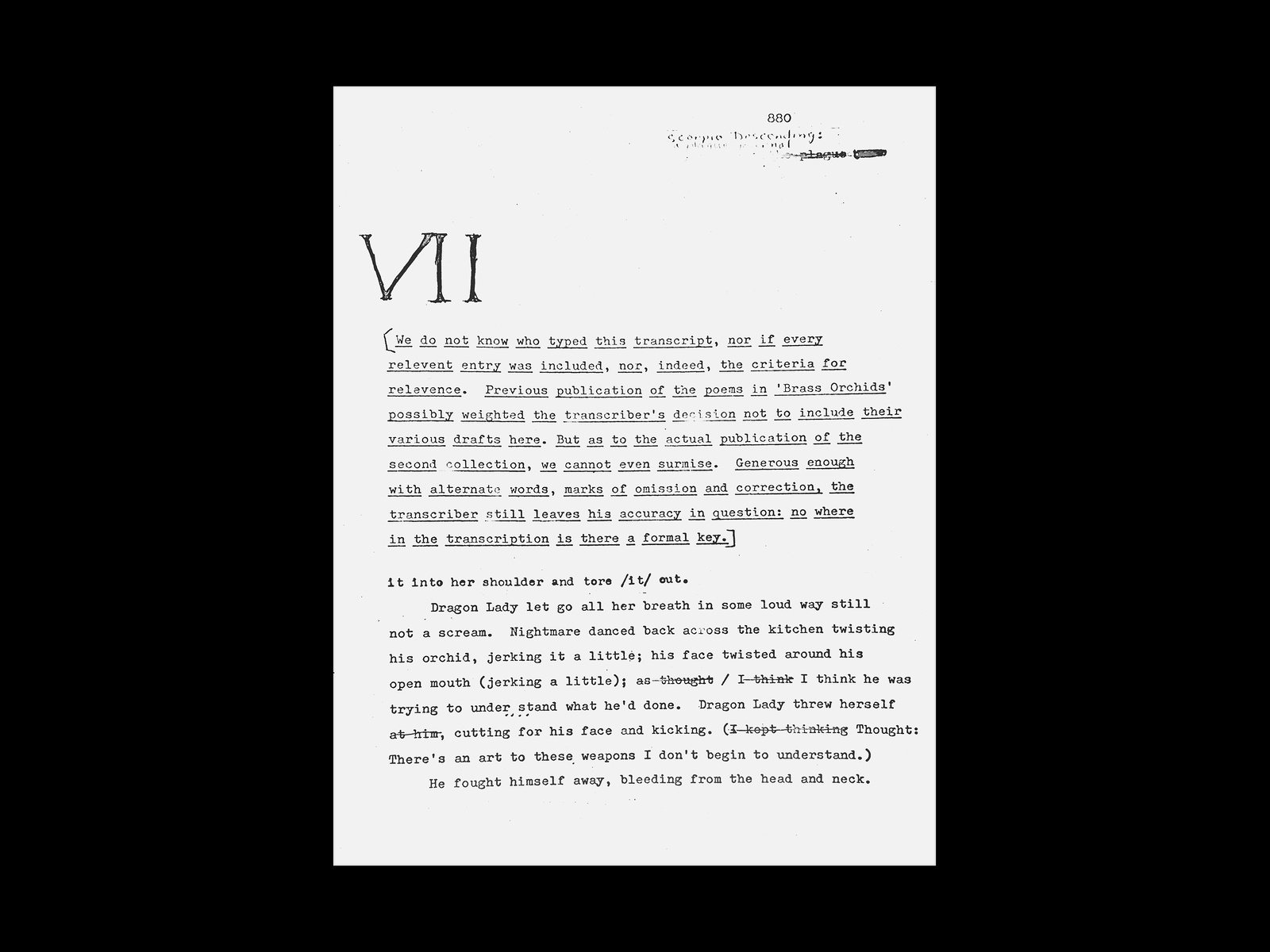

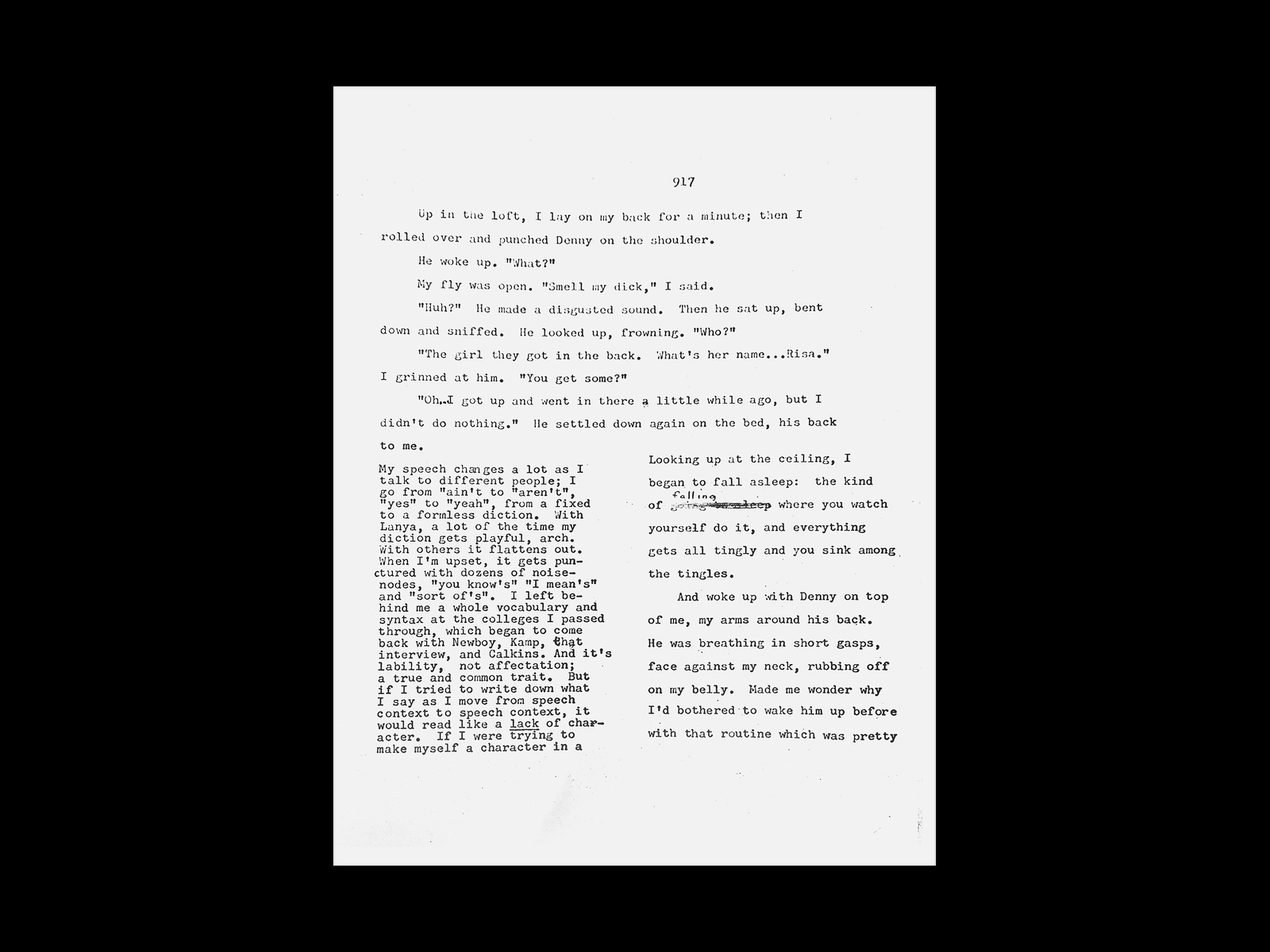

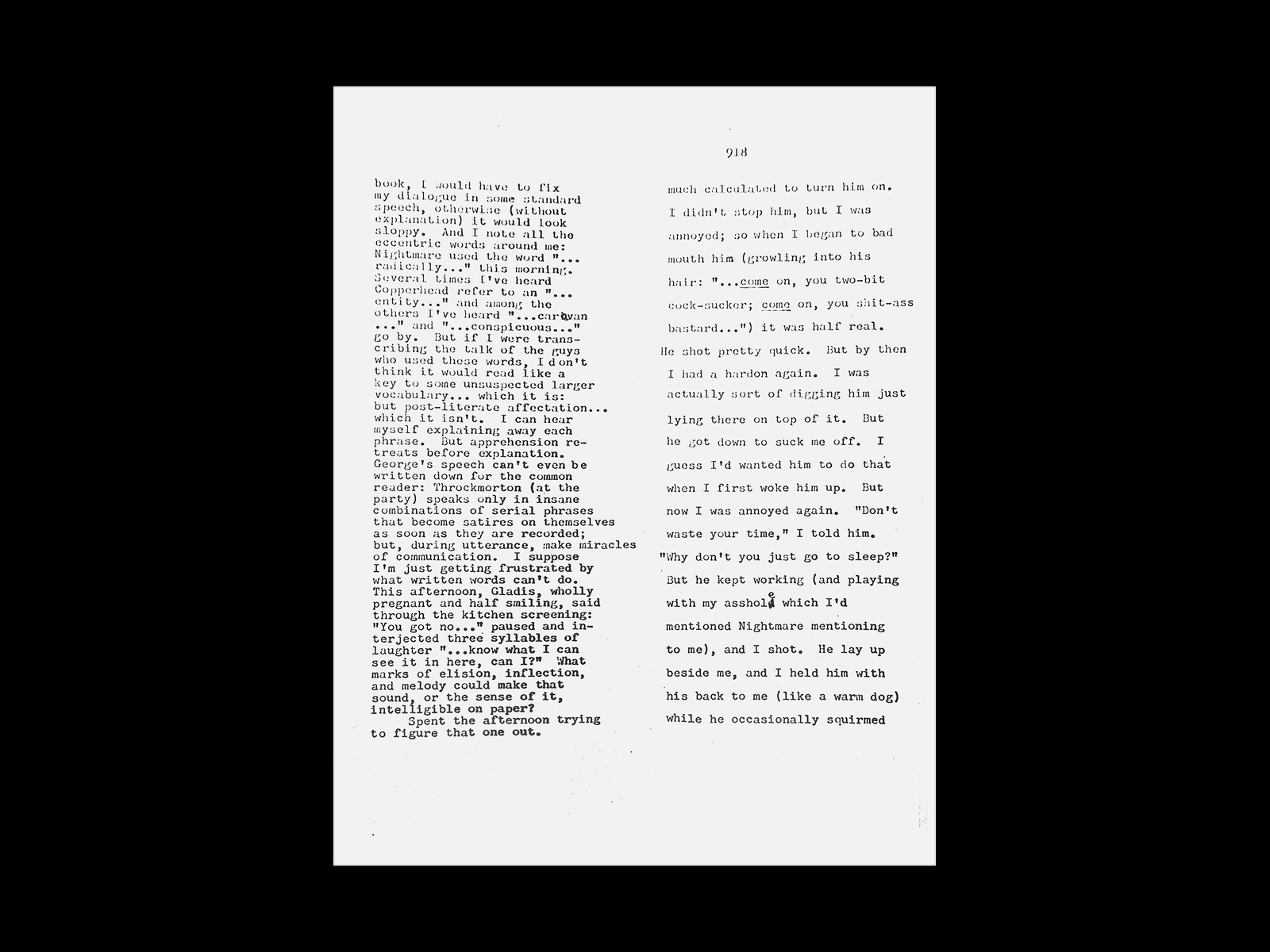

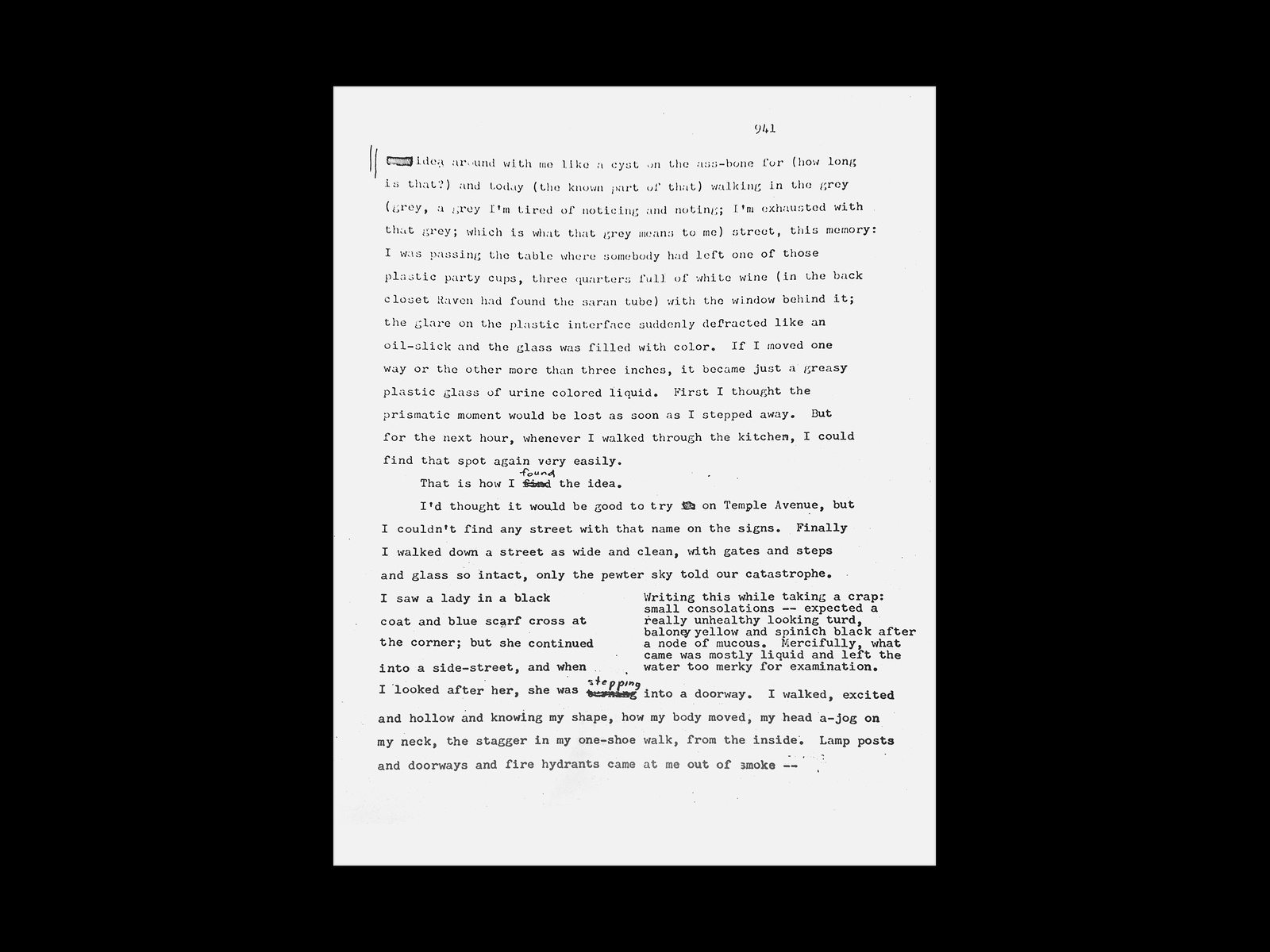

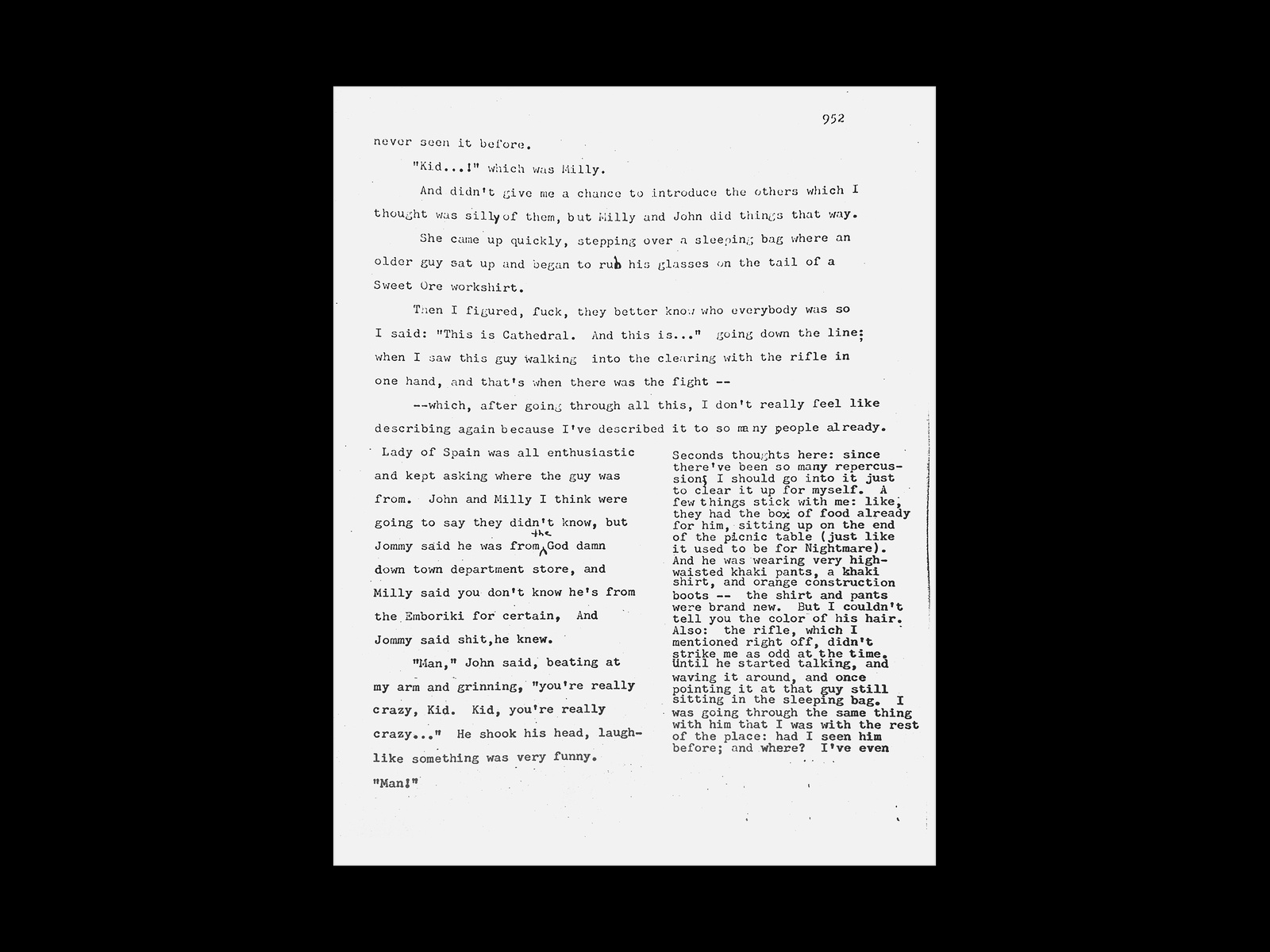

Dhalgren’s seventh and final chapter, titled “The Anathēmata: a plague journal,” is an out-of-sequence account of many of the events that were organized sequentially in previous chapters. Here the reader finds passages from earlier in the narrative reproduced exactly—it’s a common occurrence to be reading such a passage and to be struck with a faint memory of a sentence read elsewhere. “The Anathēmata” opens with an unsigned editor’s note suggesting that its contents are that of Kid’s notebook, reproduced in its raw state with corrections and annotations. The annotations take shape in distinctly graphic ways, which are represented through the chapter’s typesetting. Kid precisely corrects sentences with uneven strikethroughs, which grow less and less frequent as the chapter progresses. He wraps certain words or phrases in forward slashes to suggest that they were originally interlinear additions. And he writes short personal notes and criticisms in between or around the chapter’s primary text. These personal notes and criticisms are represented as inset text blocks, whose padding produces white frames that change their aspect ratios according to the amount of text needed from spread to spread. They’re typeset in six-point News Gothic Condensed, distinct from the rest of the novel’s nine-point Times New Roman. And they often begin on a recto and end on a verso, causing the reader to, say, read two pages of the primary text, flip back two pages, and then read two pages of the inset text blocks. Two possible interpretations: 1) That throughout this sequence we’re seeing Kid writing and then rewriting himself. 2) That we’re seeing Kid’s writing merge into the writing of the notebook’s previous owner, and that Kid’s outer experience is now confused with the pre-written, inner notebook. The strip has been twisted, its ends connected.

Drawings representing geometric metaphors used to organize narrative structure including Lawrence Durrell’s four-coordinate quartet, Lewis Carroll’s chess board, and Laurence Sterne’s line drawings.

Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren (Des Plaines: Bantam Books, 1975).

Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren (Des Plaines: Bantam Books, 1975).

Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren (Des Plaines: Bantam Books, 1975).

Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren (Des Plaines: Bantam Books, 1975).

Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren (Des Plaines: Bantam Books, 1975).

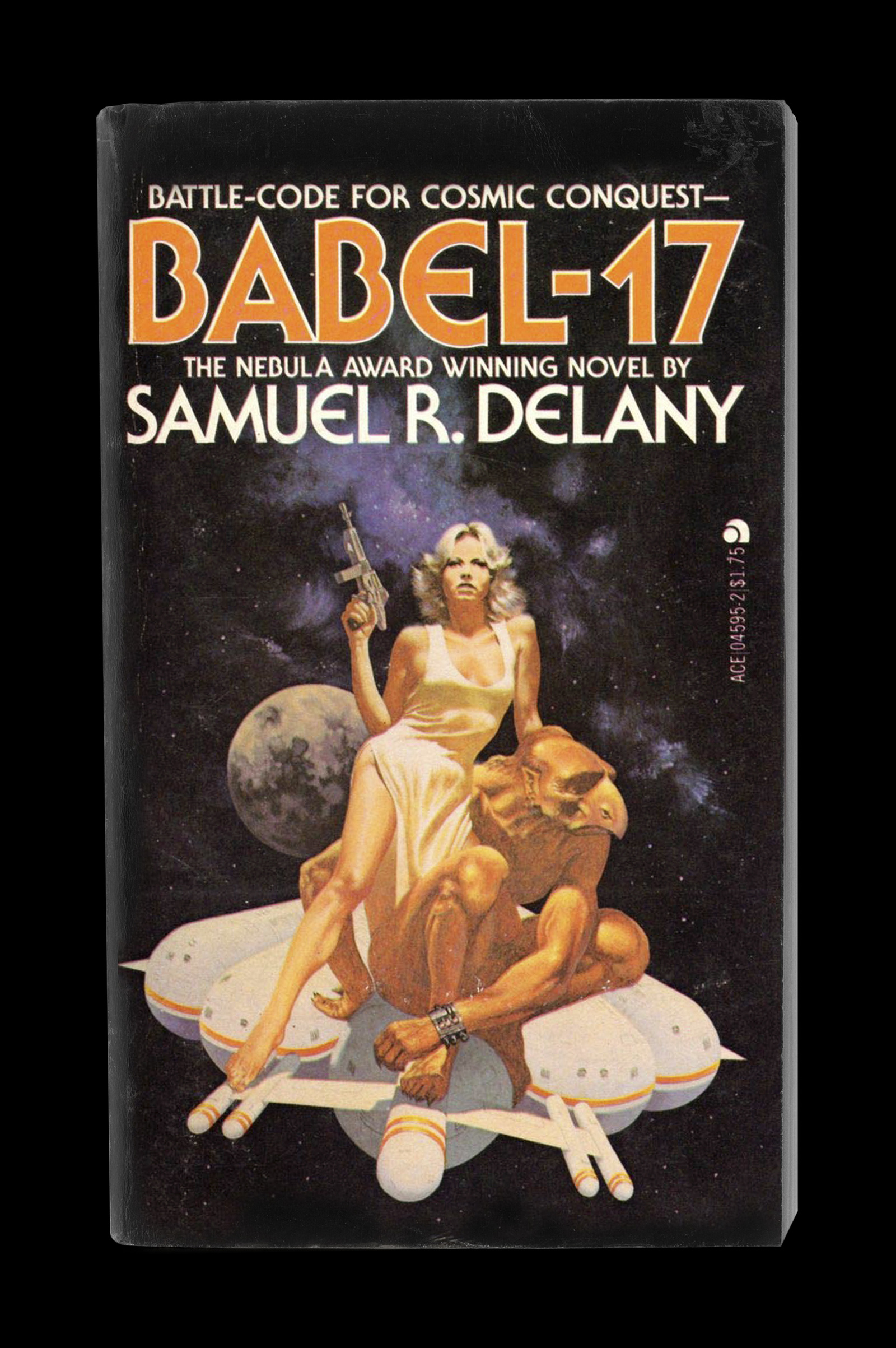

Delany conceived of this multi-channel writing method as early as 1965, while working on his novel Babel-17. Hoping to visually represent the psychic confusion of a character fostering two conflicting thoughts in two distinct languages, he proposed a similar inset text block solution and was told by his printer that such a section would need to wait for computer typesetting. Indeed, Babel-17 wouldn’t be typeset according to Delany’s original intent until its 1983 edition.2Samuel R. Delany, “The Semiology of Silence,” Silent Interviews: On Language, Race, Sex, Science Fiction, and Some Comics (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1994), p. 43. Even formatting Dhalgren’s pages this way in the mid-1970s would have been no small task. While writing the final chapter, Delany (or possibly an assistant) would have typewritten Kid’s notes as half-leaded lines, measured the necessary column height and width, blocked out this space in the main running text of the manuscript, and then pasted the half-leaded notes into the given space. The manuscript, hand-drawn strikethroughs and all, would have then been passed on to a typesetter, who would see to it that the two distinct columns shared the same overall vertical measurement, and that the inset columns had a standard width. All of this done while ensuring that the inset blocks and the main running text intersected at the locations Delany had initially intended. He’d continue to iterate on this visual method in the short story collection Atlantis: Three Tales (1995), and in essays from Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999) and Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts & the Politics of the Paraliterary (1999).

In 2017, Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library acquired Delany’s complete archive. Among this collection are dozens of boxes of the author’s journals, many of which he kept while writing classics such as Empire Star, Nova, Dhalgren, and Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand. In early 2019, I began taking once-a-month day-trips from New York to New Haven to read through these journals. This research grows out of my firm belief that not all typographers are trained as such, and that visually-minded authors, who understand their subjects deeply but might have little technical command over the way their work looks, can contribute vital formal study when they work as or with the designer, the typesetter, the printer, or the publisher in this way. Such studies might raise aesthetic, and so logistical, and so financial, and so structural, and so political questions about various publishing initiatives.

Starting with Delany’s journals from the mid-1970s and working my way backward, I was hoping to find notations and research methods he might have employed to organize and produce the text-images in Dhalgren’s final chapter. While I gathered some material insights from looking at the novel’s manuscript, I ended up using more of my days to parse entries on the inadequacies he saw in the belief that any picture of reality underlies language. Such concerns are present in much of Delany’s fiction. In Babel-17, he uses the hypothesis of linguistic relativity—that the logic of a language orders its speaker’s perception—as the basis for a weapon used by one civilization to dismantle another. In a journal from 1973, at the end of a long meditation on language’s tendency to enforce binaries, he proposes the following:

Samuel R. Delany, Babel-17 (Ace Books, 1966).

You cannot make a logical language: you can merely revise language to make it model more or less reasonably a given empirical picture of reality. We have had, in the last hundred years, many radical revisions in our empirical reality picture. We will probably have to have some radical language revisions soon if language is not to fall into complete uselessness and untrustworthiness in a way only hinted at by the McLuhans and the Marcuses.

Three or more language revisions:

1. No sex for pronouns, and a [unfinished line]

2. An animate and incarnate pronoun with running tags:

he, him, his

it, it, its

3. Separate possessive;

genitive;

associative;

4. Sense verbs working in the proper direction, with much range for response

5. Simultaneous punctuation mark “ ⋮ ”

6. Binary verbs: “To true” and “to false”3Samuel R. Delany Papers, Journal #57, England 1973, Box 17, Folder 1. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

I made a specific note of the fifth item in Delany’s list. I found another mention of it in a different journal from the same year, just before an essay he wrote on his frustration with cybernetics’ approach to linguistic modeling4Delany expands on this subject in his essay “Some Remarks on Narrative and Technology, or: Poetry and Truth” (1995).:

A simultaneity mark: “ ⋮ ” means that narrative time has stopped and what happens on both sides of the mark are simultaneous.5Ibid., Journal #59, England 1973, Box 17, Folder 3.

In mathematics, “ ⋮ ”—also known as “vertical ellipsis”—is typically reserved for marking a missing term in a matrix that reads from top to bottom. Where a single value is unknown or general duration to be suggested, the three vertical dots will appear. With the invented application he suggests for this mark, Delany proposes an impossibility: that the reader take in two or more actions in the English language’s typical left-to-right reading order, but, in recognizing the mark separating these actions, understand that they occur in perfect sync with one another, and not side-by-side in a narrative timeline. This proposal raises some immediate questions: How does one denote durations of these two discrete actions? Does “ ⋮ ” signify that the two actions surrounding it are of the exact same duration? Is it possible to place this mark between three, four, five, or more actions? What if it replaced all the periods in a text? How could a text that prioritizes simultaneity be read aloud? Would a text written with this mark degrade or enrich narrative? Is linear narrative necessary?

I have not seen this invented punctuation mark in use in any of Delany’s published writing, and so have little evidence as to the seriousness with which he wrote the above journal entries. Simultaneity, the presentation of different views of the same subject, might have proven useful while Delany was writing, say, a prolonged sexual encounter in Dhalgren or Hogg. Consider all of the strange little inborn movements that Risa goes through in one of Dhalgren’s orgy scenes: her hand grabbing air, her vagina being penetrated, her toes spreading widely, her heel digging into the mattress—all captured from different perspectival points and condensed into a singular narrative inst(ruction to read a flash of all that unconscious movement of flesh with abandon, w)ant. The same could be said of that vital moment when Kid climaxes, at once coming inside Risa and receiving a detailed vision of himself running through a dark forest with a screaming, unidentified companion.

In addition to its narrative function, a simultaneity mark might help visualize multiple, contradictory ideas within an author’s mind, or to provoke skepticism about the hierarchy of a left-to-right reading system. It’s a general narrative expectation that texts follow a logical progression and work toward a conclusion, organizing the things that have been going on such that the reader can see them resolved and then stop thinking about them. Simultaneity might serve as an admission that many events worth writing about simply don’t conform to narrative logic. The compression of time implied by the simultaneity mark is an acknowledgement of the compromises that authors often make to translate actions into written sentences. These are compromises that, when recognized, might be avoided in favor of encouraging complexity, what the writer Saidiya Hartman expresses in a 2018 interview by saying, “[My friends who are poets think of narrative] as being about closure, about teleology, nothing exciting can happen in narrative. It’s so often that narrative is the vehicle for the reproduction of a certain way of looking at the world, a conceptual prisonhouse. I’m working with this degraded material, this degraded form that is narrative, and seeing what I can do with it.”6Saidiya Hartman in conversation with Thora Siemsen, “Saidiya Hartman on working with archives,” The Creative Independent (2018).

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Samuel R. Delany Papers, Dhalgren typewritten manuscript (1972). Box 77, Folders 9–14. James Weldon Johnson Collection. Marjorie Content Papers and Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Although composed of two voices, Dhalgren’s final chapter doesn’t produce an easy binary. In addition to reading one column and then the other, the reader can stop reading and start looking at a spread as a kind of text-image of two simultaneous channels. It’s the visualization of two separate voices at once or the visualization of the same voice speaking at different times and then braided together into one moment. Its texture slowly changes from spread to spread as one voice oscillates between fore- and background.

The reader’s challenge: between any two actions, no matter how together, there is a boundary that divides our singular attention away from one and toward the other. Like the unspeakable, the simultaneous occurs in and relies on “the column you are not reading.”7Samuel R. Delany, “On the Unspeakable (The Capri Theater, Times Square, 1987),” Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts & the Politics of the Paraliterary (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1999), pp. 58–66. It could be a reading that asks us to ignore this split. To accept simultaneity as a fundamental challenge to our understanding of reading as a succession or sequence. To abolish reader’s time and substitute author’s time.8I’ve borrowed the terms “reader’s time” and “author’s time” from the Gregory Rabassa and Paul Blackburn translation of Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela (Hopscotch) (1963). To have many subjects occupying the same space all at once.