#1: An Introduction to Steganography

Steganography is the practice of embedding secret messages within openly accessible information systems. For centuries the tactic has been used by underrepresented communities as a tool for protection, survival, and resistance in the face of oppression. Today, in an age of permanent surveillance, steganography remains a powerful strategy for groups looking to subvert inequitable structures of power and exploitation. In the ongoing column Dark Cousin, artist and designer Amy Suo Wu offers embodied reflection into the evasive territory of the visible and invisible, and takes us down a meandering path of coded language throughout history.

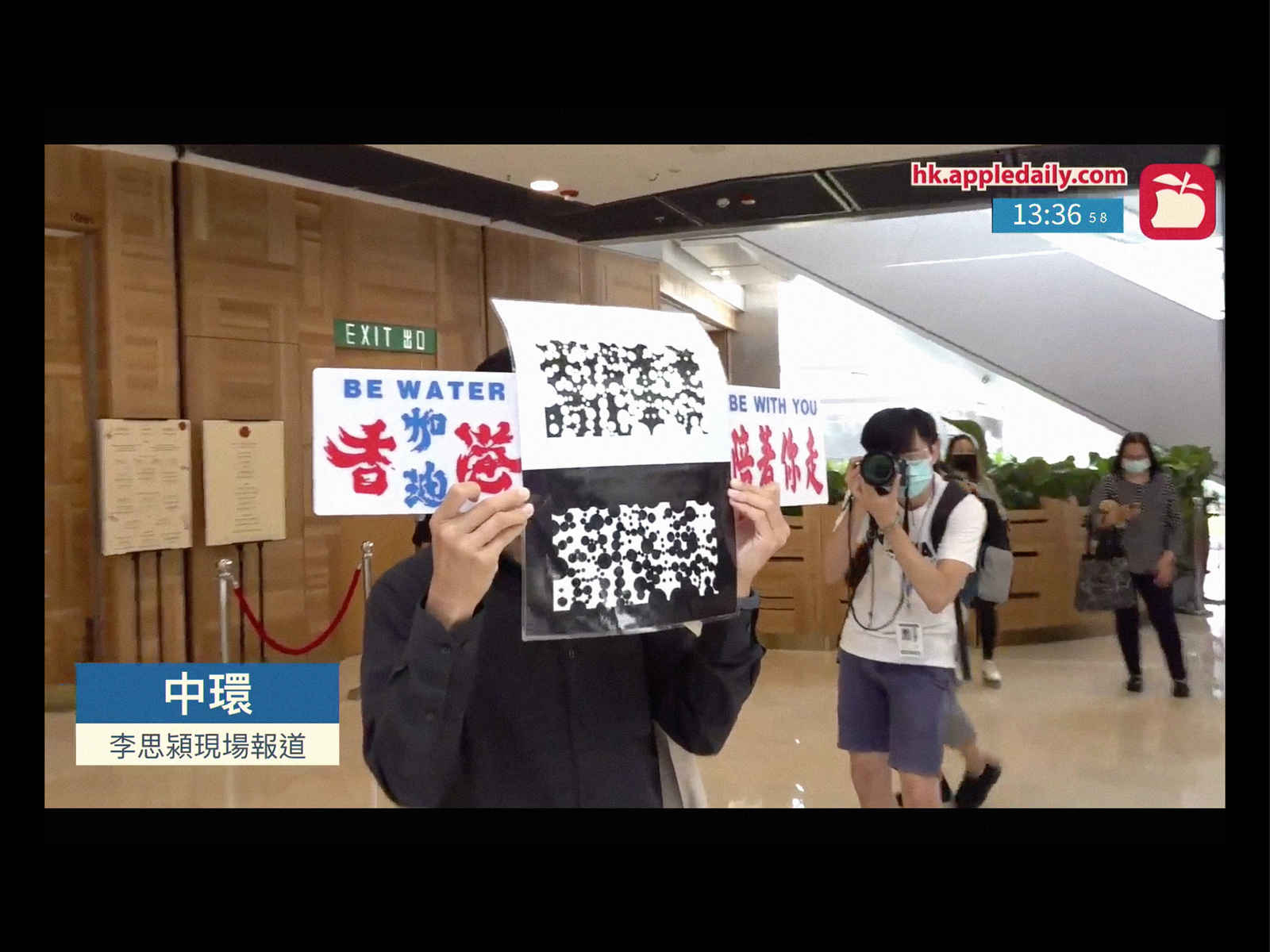

Since Beijing’s new security law was signed into effect in Hong Kong on June 30th 2020, protesters have responded to the political censorship with a wealth of visual and linguistic evasion tactics. Among the most intriguing to me are the tactics that include taking advantage of the phonetic qualities of the Chinese language. Because Chinese dialects like Cantonese and Mandarin are tonal, the same word can take on different meanings when pronounced with a different emphasis and pitch. For example, when the banned slogan “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times” is pronounced another way it sounds like “bacon and sausage, vegetables and noodles.”

This homonymic feature has long been a tool for creative political dissent within Mainland China. In recent years, for example, the feminist movement in China has faced a crackdown from the state, resulting in activists being arrested and feminist discussion being censored online. When the hashtag #metoo was blocked on the Chinese micro-blogging platform Weibo in 2018, users soon found phonetic ways to circumvent online censorship. Me too pronounced in Chinese becomes “mi tu” (米 兔 ) or “rice bunny,” and so the emoji hashtag was born.

“Me too” becomes “mi tu” (米 兔 ) or “rice bunny”

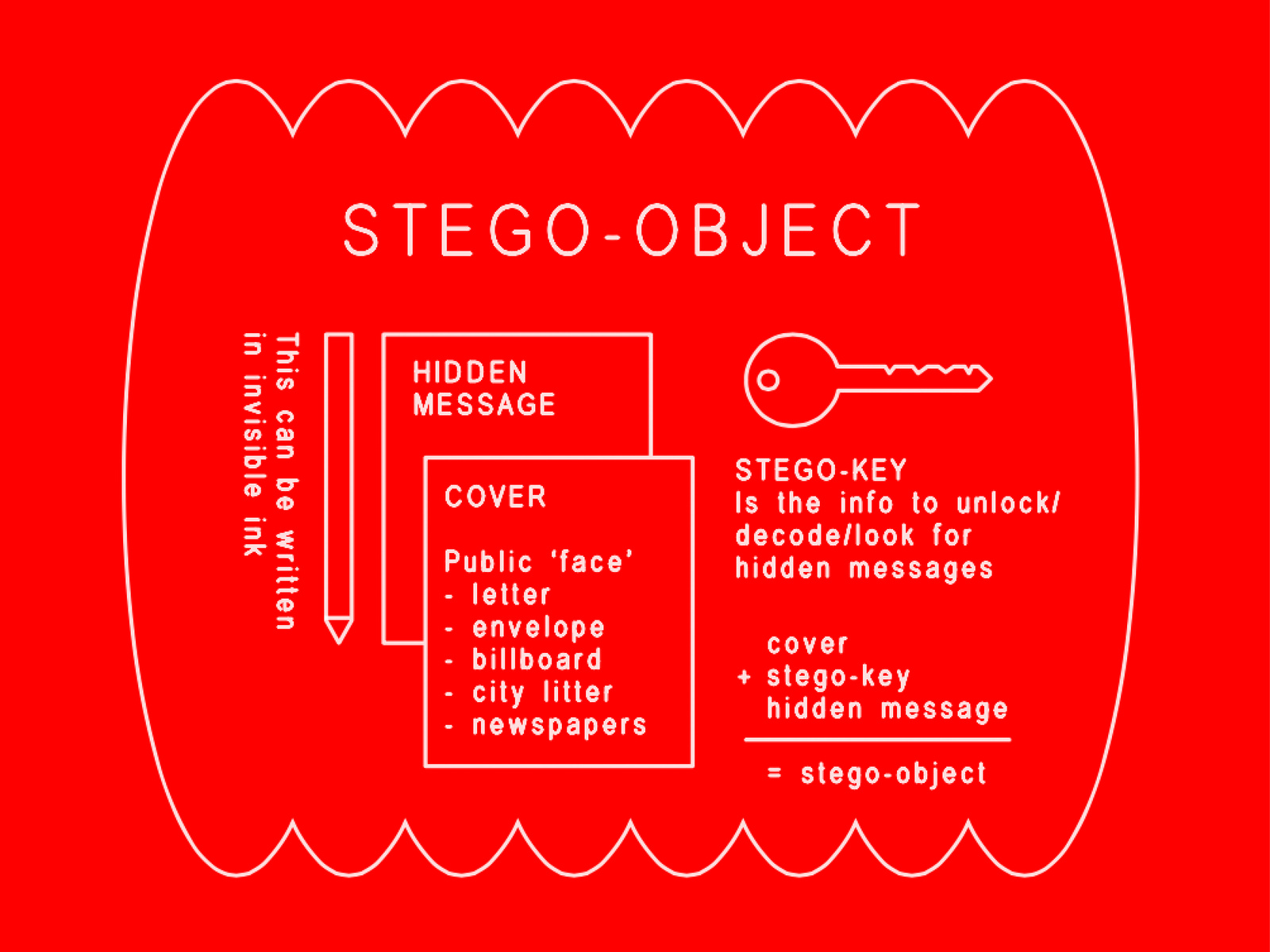

Since 2015, I’ve been immersed in the shapeshifting practice of embedding secret messages within openly accessible information systems. This practice is called steganography, and simply put, it is the art and science of hiding in plain sight. Along with the phonetic resistance in Hong Kong and China, steganography can take many forms, such as words hidden in pictures, coded textiles, messages embedded into buildings, invisible inks, and jargon code.

Steganography is often used in military intelligence, state espionage, and other top-down strategies of control and manipulation. But I prefer to study it as a bottom-up tactic of resistance, used socially and politically by women, queer communities, prisoners, and those who live in places with restricted freedom of speech, to speak out in ways that offer some form of protection. To me, these instances of secret writing are a reminder that resistance, at whatever scale, is possible. I hope to share them here in this column with you.

The phrase “bacon and sausage, vegetables and noodles” which when pronounced with different emphasis can be understood as “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times”

A sign containing the hidden protest message 光復香港, 時代革命” (Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times). The text becomes visible when staring at the sign and squinting, allowing the circles to blur together.

Needlepoint made by British POW Major Alexis Casdagli while detained at a Nazi prison camp. Casdagli hid, using Morse Code, “God Save the King” on the outer border and “Fuck Hitler” on the inner border.

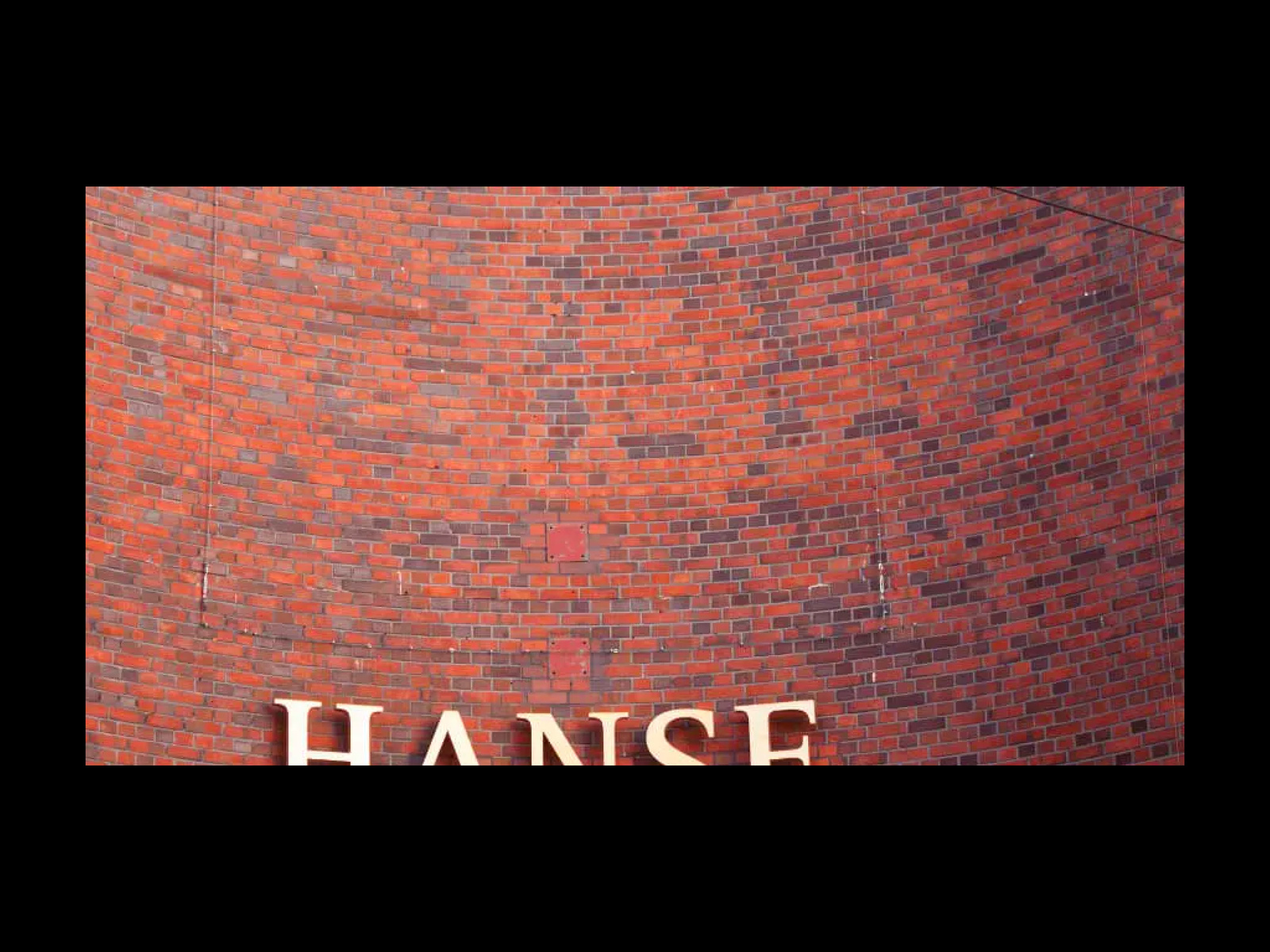

On the facade of the Hanse Viertel shopping mall, beneath the chimes, the word “POLEN” is spelled out using a darker shade of brick. The hidden message expressed solidarity from the brick masons to the “Solidarnosc” workers union.

Detail of Hanse Viertel facade.

At the heart of steganography is the instrumentalization of the seemingly innocuous. The skin of a steganographic object blends in with its environment, deflecting the unknowing gaze of the onlooker. If you know how to unlock the code, you might find steganography in the facade of a shopping mall, stitched into a tapestry, or encrypted on a protest banner. Steganography can thus be seen as a practice of camouflaged communication. In this way, steganographic principles are akin to the principles of disguise, illusion, abstraction, masking, and mimicry.

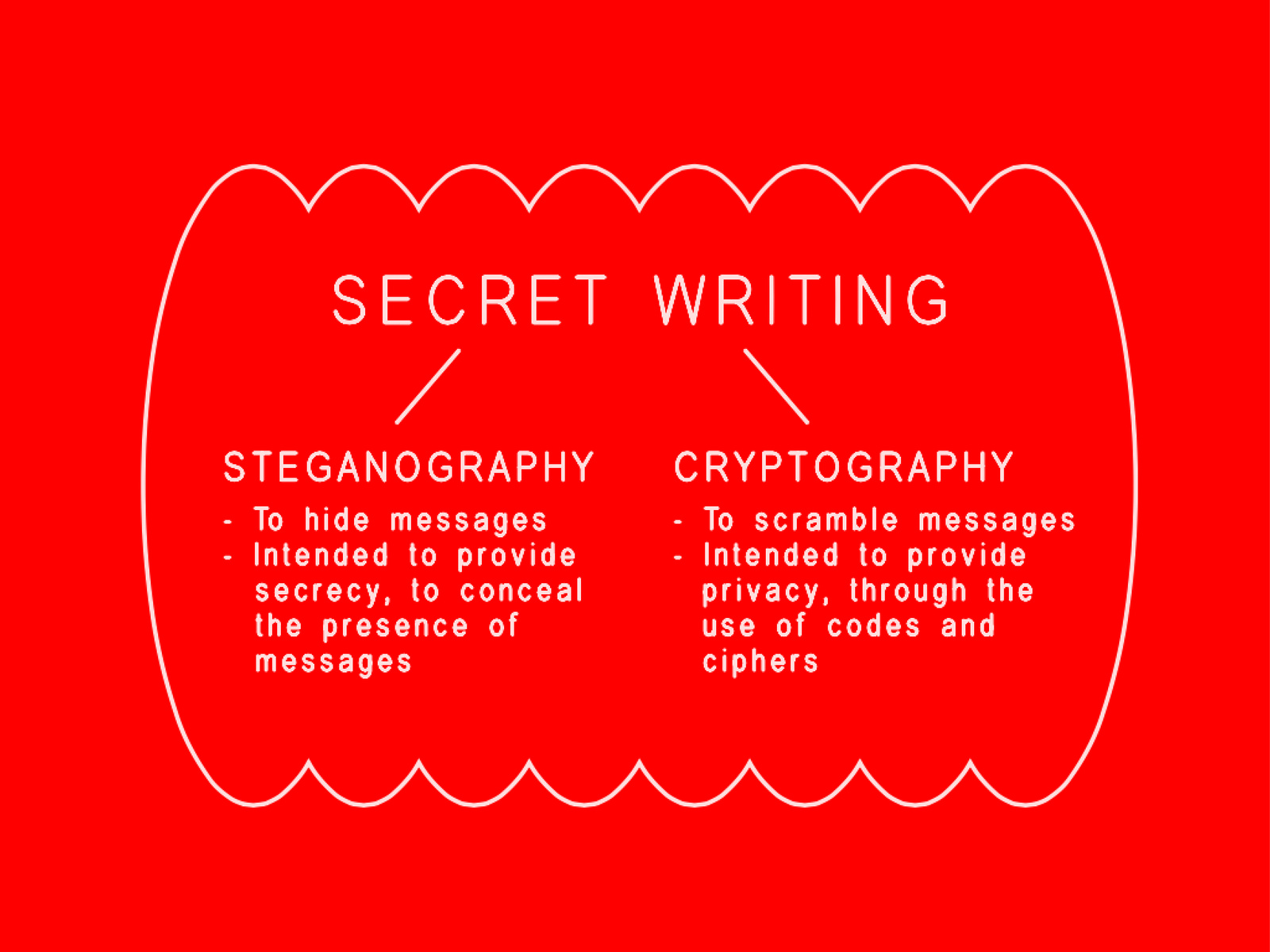

Steganography can often be confused with cryptography, another form of secret writing that uses mathematical methods to scramble and encrypt messages. These visibly scrambled letters and numbers generally make cryptography easier to spot, which is why cryptography has been called “overt secret writing,” and steganography “covert secret writing.” Whereas cryptography is a mathematical endeavor, steganography is steeped in alchemy, magic, and mystery, and as such has long flown under the radar. Kristie Macrakis, an historian on invisible ink, aptly described steganography as “cryptography’s dark cousin.”

This is one of the reasons that I’m interested in steganography over cryptography. Another reason is that as a designer/artist/educator, I’m drawn to steganography as a primarily visual and linguistic undertaking that explores the aesthetics and politics of the invisible. As a practice, it is as much about revealing and making visible as it is about hiding and concealing. In fact, it is the negotiation of both.

Grass Mud Horse or Cǎonímǎ (草泥馬) is a mythical creature and Chinese meme used to evade online censorship policies. It is a play on the Mandarin words cào nǐ mā (肏你媽) which translates to “fuck your mother”.

In this column, I’m also excited to explore steganography as a conceptual frame, and how it might be expanded to think through ideas of cultural assimilation and social invisibility—ways in which bodies and histories are made invisible. Whether consciously or unconsciously performed, many marginalized people of color attempt to blend into the majority population by emulating its language, dialect, accent, movement, clothing, or behavior. This is often a means of survival, protection, and opportunity, and it’s known as code-switching, wherein social, semantic, or linguistic codes shift based on the social context. On a macro level, the larger process is cultural assimilation, whereby a mirroring of the dominant culture is often required to be seen as an equal to the majority.

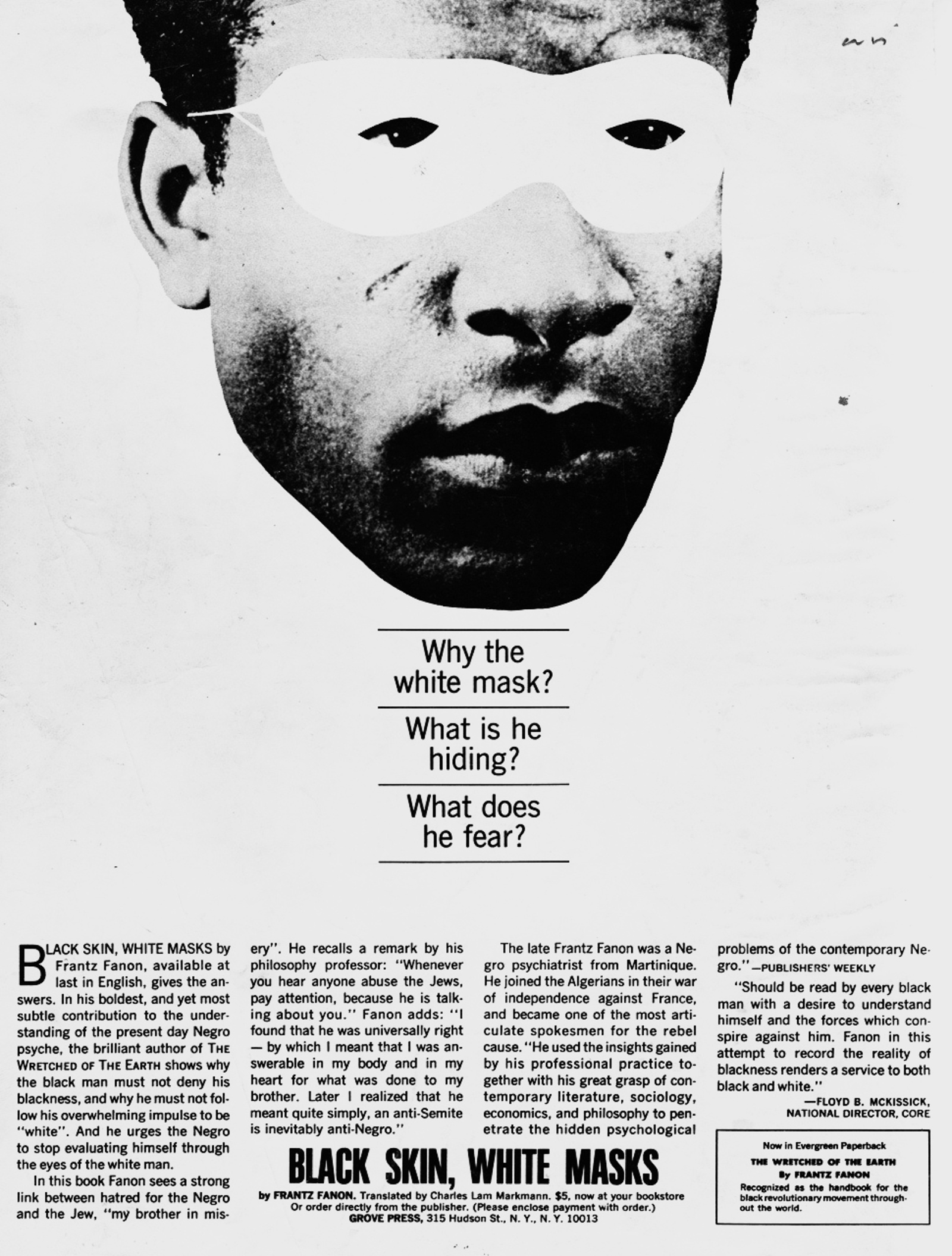

The practice of code-switching as survival is what I would describe as “tactical embodied steganography,” the condition of hiding in plain sight. These tactics might co-opt gender roles and racial stereotypes, as oppressive as they are, as forms of resistance and protection. This is not without ramification: An attempt to hide oneself in plain sight can have psychological consequences, similar to what W.E.B Du Bois calls “double consciousness,” Frantz Fanon calls “inferiority complex”—a deep shame toward oneself—and Cathy Park Hong calls “Minor Feelings,” a racialized range of emotions as a result of being invisible and unrecognized.

As the child of Chinese immigrants growing up in the Western suburbs of Sydney before immigrating to Rotterdam in 2006, one could call my life a steganographic experience. I’ve long felt like an imposter covering up the secret that I didn’t really belong in a world that is dominated by what bell hooks calls an “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” I unconsciously code-switched to survive. Looking back, this was probably why I gravitated towards secret writing in the first place. Delving into a subject that explores layers of visibility gave me an opportunity to work in shielded ways without the terror of judgement and abandonment, because hidden inside me was the incessant message that that being me wasn’t enough. It was due to this research and the friends that I met along the way that I, in equal parts painfully and serendipitously, reckoned with the complexities of my own identity.

Advertisement for Frantz Fanon’s book Black Skin, White Masks where the idea of “inferiority complex” is addressed