Shifting Symbols:

The Gender Star

The gender star is an asterisk placed within German nouns to denote gender inclusivity and neutrality. A radial representative of omission, transition, and change, the asterisk here can be considered a kind of shifting symbol. Alongside its sister glyphs ♀ ♂ #, these are common symbols that are adapted for a new purpose, a call to action for those who read them. Some attempt to repair, while others invite, gather, empower, or protest, but they are all entangled. In the essay below, Meg Miller writes about the asterisk in its latest iteration as the gender star. Woven throughout is a visual essay by Laura Coombs and Mindy Seu that offers an abridged history of shifting symbols.

Shifting Symbol 01: Asterisk

A hand-painted asterisk—each line a thick brushstroke—was used in the promotional poster for an exhibition in the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at M.I.T. in 1974 when Otto Piene was director. The asterisk was enlarged and printed in the Visible Language Workshop at M.I.T., co-founded by Muriel Cooper. This asterisk became the aggregate symbol of this group, with the point of each line representing a different fellow. Asterisks are also used to note omission, addition, censorship, emphasis, and, nowadays, corrections*** to typos while texting.

How do you pronounce an asterisk? Not the word but the symbol, the actual typographic mark. That five-sided star that’s tacked onto words, floats above letters; the smattering of hatch marks written quickly by hand, a neat little tick typed on the computer, or with ends as swollen as the petals of a cartoon flower. Some symbols aren’t meant to be spoken, and the asterisk seems to be one of them, though it’s silently understood in all its various positions: Affixed to the end of a sentence as a footnote, an addition, a correction, or an afterthought. The staid stand-in for the vowels in a profanity; an expression of *emphasis.* A bullet point, an ornamental separator between sections, a bejeweled breath between texts. The asterisk is voiceless but adaptive, its meanings and uses have seemingly multiplied*The word “asterisk” derives from “astrum,” the Latin word for star, and stretches back to Hellenistic Alexandria when scholars needed a symbol to correct classic texts, such as Homer, without changing them. Over time, it’s uses accumulated: the asterisk was used for corrections then footnotes, profanities then sports statistics, and so on. over time, reflecting the malleability of language. Most recently, in Germany, the asterisk has taken on the role of the Genderstern, or gender star, a symbol that denotes gender-neutrality when tucked into the middle of the language’s gendered nouns. In spoken language, the gender star is pronounced as a pause.

“Liebe Designer*innen—das solltet ihr unbedingt lesen!” my friend Ann*Designer Ann Richter of Studio Pandan says in a voice message sent over text. It’s a demonstration, a phrase simple enough to be understood by a German language novice—Dear designers—you should definitely read this!—but I’m also listening closely for the unspoken. After “Designer” is a clipped pause, nearly quick enough to miss, before the feminine plural ending -innen. It’s what’s called a glottal stop in linguistics, a brief stop of air flow in the vocal track, as between the vowel sounds in uh-oh. In Ann’s sentence, the stop means asterisk and the asterisk means that the designers in question are not specified as male (der Designer) nor female (die Designerin), but as designers of mixed or indeterminate, of any or all, genders (die Designer*innen). Much more than just the sign of a pause, the gender star, aloud and on paper, serves as a corrective to a long held norm, the re-insertion of a faulty omission, a tiny but persistent political statement. It’s a “typohack,” to use a term by designer Hannah Witte*Witte was inspired to coin the term ‘typohacks’ after reading Anja Neidhardt’s writing about the gender star, in which she uses the term hacking for gender-sensitive language forms (cited later in this piece). Witte’s thesis publication Linguhacks / Typohacks provided much of the foundational research for this piece.—an imperfect but necessary quick fix as language catches up with cultural and societal change.

In the German language, nouns are either masculine, feminine, or neutral. A male singer is a Sänger while a female is a Sängerin. Plurals of course are gendered too, making two or more female singers a group of Sängerinnen, though even the presence of one male singer will turn an entire chorus male (Sänger)*To borrow an example from Luise F. Pusch. This linguistic sleight of hand is called the generic masculine, a term also familiar to English speakers, as it describes the stand-in of masculine pronouns or masculine-specific terms for all of humanity (*sigh*). Though language purists still argue for the innocuousness of using he as a shorthand, and the inconvenience (he or she) or grammatical incorrectness (they) of inclusivity, there’s been a notable shift away from the generic masculine in recent years. In Germany there are similar debates, though any solution is more complex than swapping out pronouns or inventing a new one (ze). That’s because addressing gender equitability in the German language means addressing thousands upon thousands of nouns, with their gendered articles (der, die, das) and gendered suffixes.

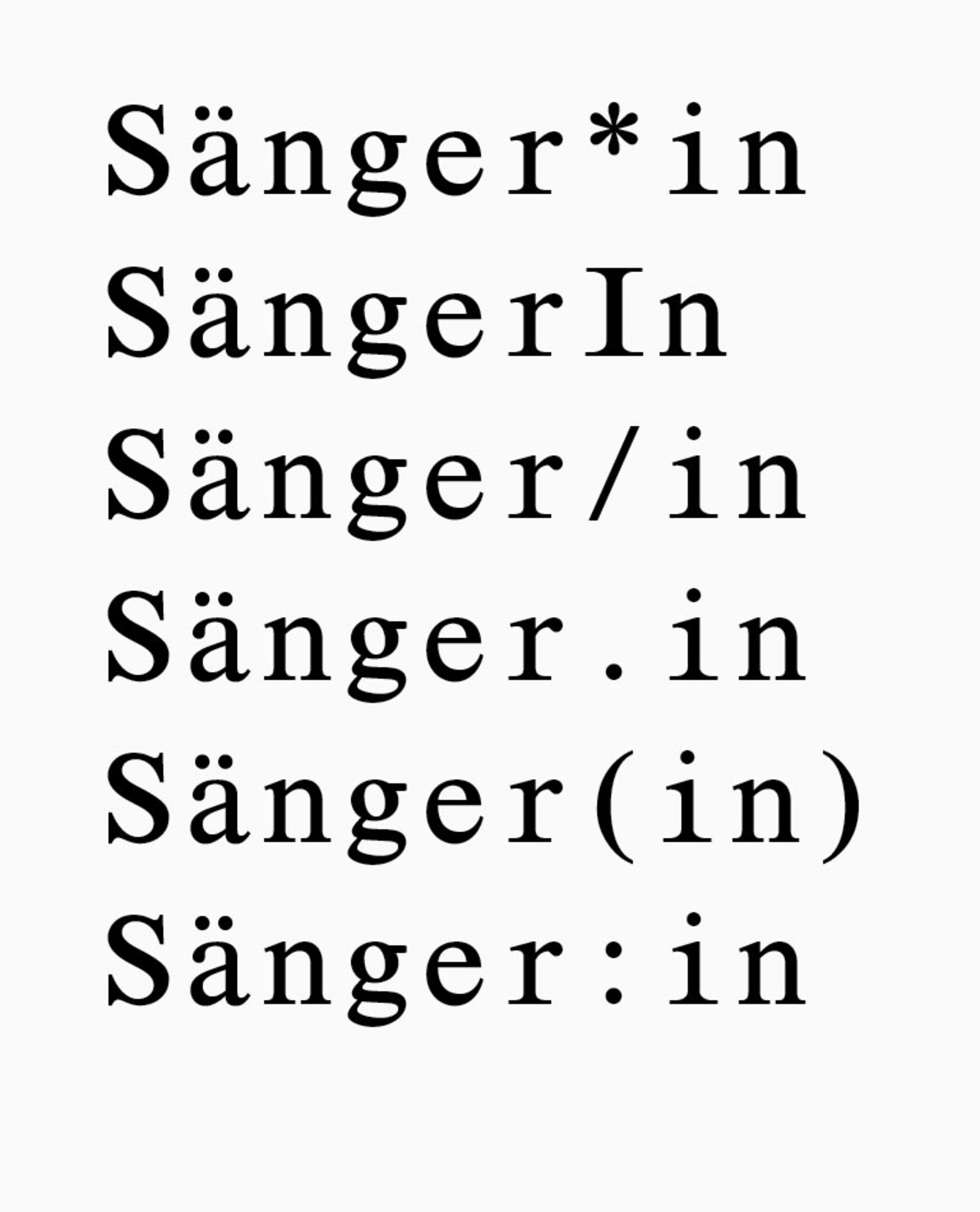

Various “typohacks” in use

Shifting Symbol 02: Male-Male-Female-Female

The male-male-female-female symbol appeared at the bottom of the 1997 webpage “darKcoRe” by the artist GashGirl, otherwise known as Francesca da Rimini. Originally a 3D render of two gold female symbols and two silver male symbols, the stems of each float and interlock into the circle of the next, creating an entangled loop of gender markers and fluid relational possibilities.

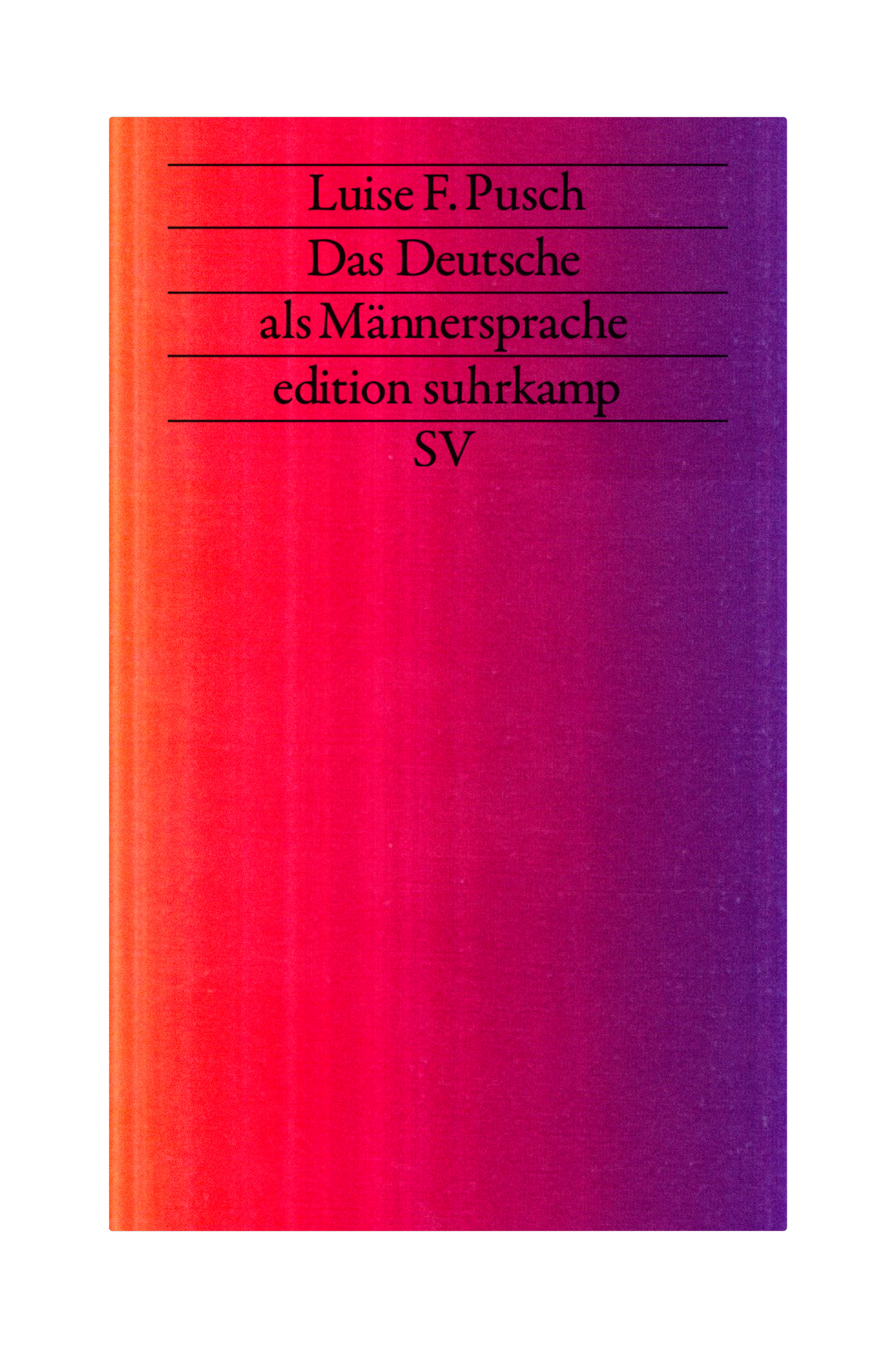

It’s a big task for a small star. But the asterisk is only the latest in a string of inventive linguistic solutions that stretch back decades, to the late-1970s. “Previously, there was no room [for women] in these mountains, called ‘mother tongue’ (of all things),” writes the feminist linguist Luise F. Pusch, author of Das Deutsche als Männersprache (German as a Men’s Language). Pusch was one of a group of linguists who in the ’70s and ’80s proposed that the German language was antagonistic towards women, giving as a prime example the use of the generic masculine in mixed or unspecified company. If students, professors, employees, bosses, and politicians were masculine by default, they reasoned, it rendered women practically invisible in these spaces, and that didn’t mirror reality. These linguists proposed the use of the Binnen-I, or “inner I,” which inserted a capital “I” into the feminine suffixes (-in or -innen) to signal that a word could be either male or female.*The Binnen-I was invented by journalist Christoph Busch, who described it as “the sexual maturation of the ‘i’ by growing up to become the ‘I’ as a result of frequent contact with the backslash.” Pusch had co-authored the first gender-equitable guidelines a year earlier, and other linguists took up his proposal. The main benefit to this typographic solution was economy: instead of having to say or write Sänger und Sängerin in a language already characterized by lengthiness, the use of SängerIn would imply both genders in one word. The capital “I” also has the benefit of being seen but not heard, so that when speaking it just sounds like you’re using the generic feminine, a kind of corrective*Luise F. Pusch recommends that for the next two to three thousand years we use only the generic feminine, as a form of compensation. to hundreds of years of the opposite.

Luise F. Pusch, Das Deutsche als Männersprache (1996)

Predictably, the Binnen-I had its critics, who complained that it didn’t comply with official language standards*Though Germany doesn’t have a national linguistic arbiter, a council for orthography sets spelling rules in schools and official bodies., that it was clunky or ugly or unnecessary, that changing language is sacrilege, as if language isn’t changing all the time. But it was adopted widely among feminists, and has held on throughout the decades even as other typographic conventions have been introduced, like the use of the slash (Sänger/in)*The slash has been used since the 1960s., colon (Sänger:in), period (Sänger.in), or brackets (Sänger(in)). You’ll still see the Binnen-I used sometimes today. In the 1990s, feminist linguist Matthias Behlert proposed that it was only fair to add a masculine ending and a third ending called divers (diverse) to accompany the feminine ending. The female ending would stay the same, sans male ending (Sängerin), while new endings for male (Sängeris) and divers (Sängeril) would be invented.*The plurals would then be: Sänginne, Sängisse, Sängille.

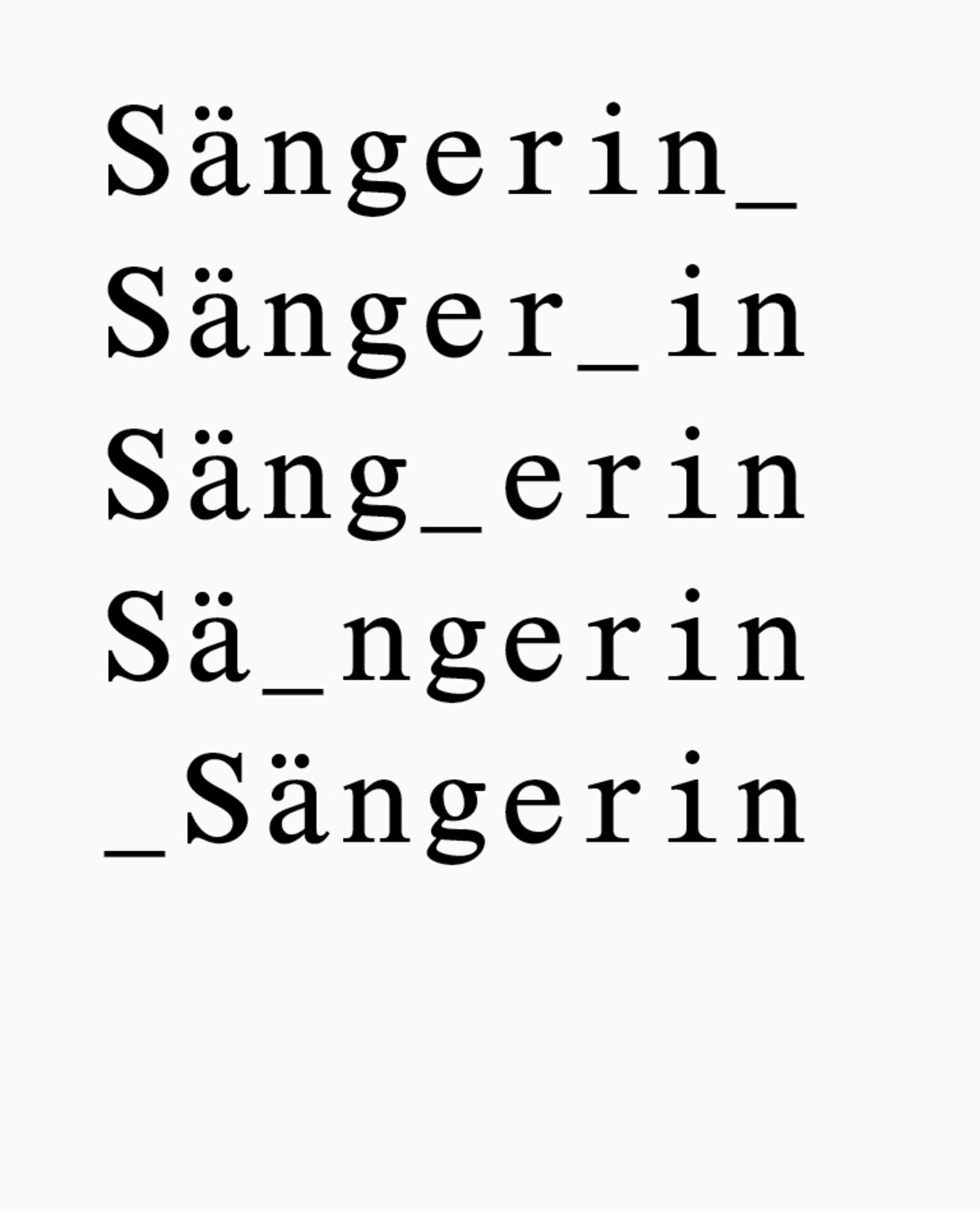

In the early 2000s, however, feminists began to discuss how the Binnen-I reinforced a male-female binary*Some noted how it looked quite literally like a divider or a wall, others mentioned its phallic nature.; the rigid capital “I” didn’t leave any room for other genders, or for those who don’t identify with a gender at all. In 2003, Steffen Kitty Herrmann came up with the gender gap, which addressed this problem. As s_he explains in a paper titled “Performing the Gap,” the gender gap is a response to how the German language’s articles and endings reinforce “the illusion of two cleanly separated genders” and deny anything outside of this binary. Hermann proposes inserting an underscore between the male and female ending, creating a blank space inside of the word, which represents everyone who identifies beyond the two-gender norm. “This marks the place that our language does not allow….Placed just between the boundaries of a rigid gender order, it is the spatialization of the invisible, the permanent possibility of the impossible.”*“Performing the Gap,” Steffen Kitty Herrmann, Arranca, November 2003. link The underscore literally pushes aside the two normative genders and makes space for you, the reader, whoever you are.

Even more poetic, I think, is the dynamic (or “wandering”) gender gap, which uses Hermann’s underscore but doesn’t fix it to the position between the male and female endings. Gender researcher Alyosxa Tudor came up with the wandering gap in response to the criticism the static gap began to garner as people took issue with the fact that the space was framed by the male and female ending, as if suggesting that those were the natural ends of the gender spectrum. The wandering gender gap isn’t relegated to sit between the norms, it can be inserted between any two letters of a word, making it slippery and chaotic, mostly annoying to read, rarely if ever used, and also my personal favorite of the German gender hacks. Too radical to be practical, I imagine the verbal version of the wandering gender gap to be riddled with glottal stops, sputtering out, breaking down language, turning mundane conversation into a kind of sound poetry.*Or as my partner’s grandma would have said “die Verhackwurstelung der Sprache”—”the ground-meat-sausage of language.”

Alyosxa Tudor’s “Wandering Gap”

Shifting Symbol 03: Hashtag

Formerly known as the sign for pound, number, and hex code, among others, this symbol is now best known as the “hashtag.” While its etymology is not clear, the name “octothorpe” comes from the Old English word for village, “thorp,” for its resemblance to a town square surrounded by eight fields. In 2007, Chris Messina proposed the symbol be used as a metadata tag to streamline search queries, tweeting, “How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups. As in #barcamp [msg]?” Now the hashtag is primarily used as an online town square, an aggregator for social movements such as #metoo.

Yet if the goal is widespread adoption (and that, too, is up for debate)*Linguist Anatol Stefanowitsch writes in Die Zeit that the gender star is a “sociolinguistic marker” that signals that the user is part of a certain community of practice—in this case, a group of people with certain ideas about gender—and that mandating its usage effectively dissolves the connection between the marker and the community. “The gender star not only loses its meaning in the narrower sense, but also its ability to convey the worldview of those who use it.” link something more subtle, shape-shifting, yet familiar, would better do the trick. It’s unclear exactly how the gender star came about, or who started using it first, but some sources date it to 2009.*In 2009, Beatrice Fischer and Michaela Wolf at the Center for Translation Studies at the University of Vienna used the star in the “Leitfaden zum geschlechtergerechten Sprachgebrauch” (Guide to Gender Equality in Language Use). There are also sources for the first written mention in 2004 by a debate group called “Gendertalk” in Vienna, though they used the * a bit differently—not in between fe/male endings but as a replacement for all genders, leaving out the endings i.e. lieb* Les*“ (lieber Leser / liebe Leserin). link In 2015 the German Green Party started using the gender star, and in 2017 the Berliner Senat adopted it. When I learned about it, belatedly, upon my move to Berlin in 2019, it had just been adopted in the official language rules for the city of Hanover, prompting backlash from the Verein Deutsche Sprache (an association for the German language), which published an open letter signed by more than 70 public figures and a petition emphatically titled “No More Gender Nonsense!”*While I was writing this essay, a well-known German author, Kirsten Boie, refused to accept the Sprachpreis, an award handed out by the VDS, because, among other reasons, the director of the council has repeatedly criticized gender-neutral speech as Genderwahn, or “gendermadness.” link

I was renting a small shared studio at the time within the offices of the German feminist magazine Missy Magazine, which had adopted the gender star and had just published a piece about the decision. The article explains that the gender star has its origin in computer science, where the asterisk is a “wildcard” symbol, and can stand in for any string of characters. “The gender star creates a form of address that includes cis and trans men and women and people who identify themselves as outside of the binary genders on an equal basis,” writes Naira Estevez, who was also tasked with looking after us renters. She adds: “We’ve chosen not to use an asterisk at Missy at the end of a word, even if the person we address is trans. Because a trans woman is a woman—not a woman*.” One of my studio mates at the time, Anja Neidhardt, a feminist design researcher and writer, noted in a 2018 piece she wrote for the magazine ROM that just as consistently as she uses the gender star in her writing, it’s edited out by design magazines. Her piece argues that designers have a unique opportunity not only to encourage the usage of gender-equitable language—“Design has the potential to reach many people, not least those who are not already sensitized to the topic during their studies and who read neither Missy Magazine nor the party proposals of the Greens,” she writes—but also to design a better symbol.

While Estevez calls the asterisk the most beautiful solution, Neidhardt notes (approvingly) that the stars are seen as “troublemakers who disturb the harmony of what we have internalized as beautiful and good and uncomplicated.” Being seen as disruptive is somewhat new for the asterisk, which comes from “astrum,” the Latin word for star, and stretches back to Hellenistic Alexandria when scholars needed a symbol to correct classic texts without changing them. Centuries later, asterisks were used to signal the omission of certain passages in the Greek translations of the Old Testament, which made it the symbol of something missing or hidden. It’s this connotation that makes the asterisk perfect for concealing a password, or gives meaning to scholar Saidiya Hartman’s description of a young Black woman’s life as “an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.”*From Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, which explores the lives of “ordinary” young Black women in U.S. cities in the early 1920s, pieced together from fragments in archives The asterisk is undoubtedly more beautiful when it’s used as an additive gesture,*As is so well articulated in Mindy Seu and Laura Coombs workshop for the Southland Institute, more* a sign of being seen, a citation, a collaboration across texts. It’s also quite beautiful in its radial form, which implies a certain non-linearity, all points leading back to the same center. Hannah Witte, who wrote her thesis Linguhacks / Typohacks on the topic, writes that the gender star symbolizes “a spectrum of many sexes, which in all directions shine.”*Witte, who argues that the real purpose of gender-sensitive hacks is to disturb the binary system, went so far as to invent the “Gender Trouble Star,” after Judith Butler’s seminal text on feminism and queer theory. The Gender Trouble Star is meant to attract as much attention as possible with eye-catching shapes and a high contrast to the rest of the text. The pause of the gender star may be so subtle in verbal speech that it’s possible to miss, but it’s hardly that in written language. A page of writing with asterisks in every sentence practically sparkles.

A page of asterisks practically *sparkles*…

Shifting Symbol 04: Eye Bolt

For the 1975 Women in Design conference, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville adopted the eye bolt, a common piece of hardware shaped like the symbol of Venus, otherwise known as the female symbol. Sheila made this symbol accessible and ubiquitous. Women could easily create their own eye bolt necklace with common materials from their local hardware shop—assembling the piece from an eye bolt, nut, and ball chain. To this day, Sheila gives eye bolt necklaces to her students as a simple gesture of solidarity and a reminder of personal empowerment.

Still, even among friends who find the gender star beautiful in theory, who firmly believe in creating a more equitable German language, whose own speech is punctuated by pauses—designers who convince their clients to use gender-sensitive language, editors who argue for its use in editorial meetings—there’s a consensus that the star isn’t perfect. Where it succeeds in disrupting a norm it also succeeds in disrupting the flow and cadence of a text and the appearance of a layout. From a design point of view, the asterisk sits conspicuously above the x-height, creates white space in the middle of a word, affects grey levels. There’s a sense that, while the asterisk works for now, it’s more of a quick fix than a long term solution, and there’s hope that the latter is still to come. Ann Richter and Pia Christmann of Studio Pandan, who regularly deal with the gender star in their work as designers,*In a workshop with prospective journalists, Richter and Christmann explored creating a website with a gender star “on-off switch.” but also as teachers, led a workshop at the Muthesius University of Fine Arts and Design where they encouraged an examination of gender-neutral language/writing. Their search for improved typographic forms resulted in critical statements as posters. Both Witte and Neidhardt nod in their writings to designer Sarah Gephart’s “Hypothetical Hack,” a thought experiment in creating a glyph for a third gender pronoun. Gephart’s experimentation in developing a new symbol, and the rather lovely results, could provide a possible blueprint for a gender-equitable otherwise. Daniela Burger, design director at Missy, puts it more succinctly: the gender star is a transition period. “Our language will continue to develop, especially in this regard, and at some point new systems will emerge that no longer have typographical deficits. I think that designers, linguists, and others will increasingly deal with the problem and thus find new solutions.”*From “Streit um Asterisk,” Anja Neidhardt, ROM, 2018.

This view is echoed by Luise F. Pusch, the feminist linguist, though she’s also vocally not in favor of the gender star. Pusch notes that even with the star, women (in the form of the feminine ending) are still positioned as secondary, taking their place after men. She’s made a two phase plan for developing a gender-equitable German language: first, use the generic feminine as much as possible, “so that the language community gets used to the fact that there are women, too.” And second, “the genders (or their delegates) sit down at a table and, similarly to the parties of a collective bargaining process, work on a compromise: a language that is fair and comfortable for both—today its better to say: all—genders.”*“Eine für alle,” Luise F. Pusch, taz, 2019. In the meantime, Pusch of course prefers the Binnen-I, but has also proposed a compromise with gender star users: an i in which the dot is an asterisk (“the icing on the cake”). Or, since keyboards don’t yet come with an iced i, an exclamation mark (Designer!n) ala the pop star P!nk. There’s also the x-form (Designx), proposed by Lann Hornscheidt, Professx for gender studies and language analysis, which echoes the English latinx and womxn, and represents Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersecting axes of discrimination experiences.*Other languages have invented different typohacks as well, such as the Spanish @ for the masc. “o” and fem. “a” endings (latin@); the French “middots” for embracing both genders in the plural forms (lecteur·rice·s); and in Hebrew, the fusion of the male and female suffixes to form a gender-inclusive plural (–imot or –otim).

P!nk’s typohack from the album Missundaztood (2001)

All rather beautiful typographic hacks, from where I sit,*As an interloper and only intermediate German speaker, with an acute but admittedly lower-stakes interest in the star, particularly when it comes to practical, day-to-day use. but there’s no denying that the gender star has taken off in a way that the other German gender hacks haven’t. This is for several reasons, the biggest of which is likely that we are farther along as a society (and Germany as a country) in accepting an expanded view of gender and equitability, and encouraging language to reflect that. But I’d also like to suggest that it’s because the asterisk is a perfect stand-in for bigger and broader change. As a gender star, the asterisk acts as a kind of joint, between endings and among genders. Though “hack” may sound like something’s breaking, the asterisk in this sense is a tool for mending, or at least for tenuously holding things together until something better arises.

In general, too, the asterisk’s nimbleness to change, having occupied so many different positions over time, make it an ideal symbol for the malleability of language itself. Language not only describes, but also shapes, reality. It holds our thoughts, structures our ways of knowing, defines the boundaries of our perceptions. How botanist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer describes sweetgrass I would also attribute to the asterisk in regards to language: “It thrives on disturbed edges.” In its most common usage, as an indicator of footnotes, the asterisk has long represented what’s been relegated to the margins, literally and figuratively—that which doesn’t make it into the official narrative. It’s fitting that as the gender star, the asterisk not only represents those previously omitted, but is also writing them back in.