Remembering Lesbian-Socialist Publishing in 1970s Missouri

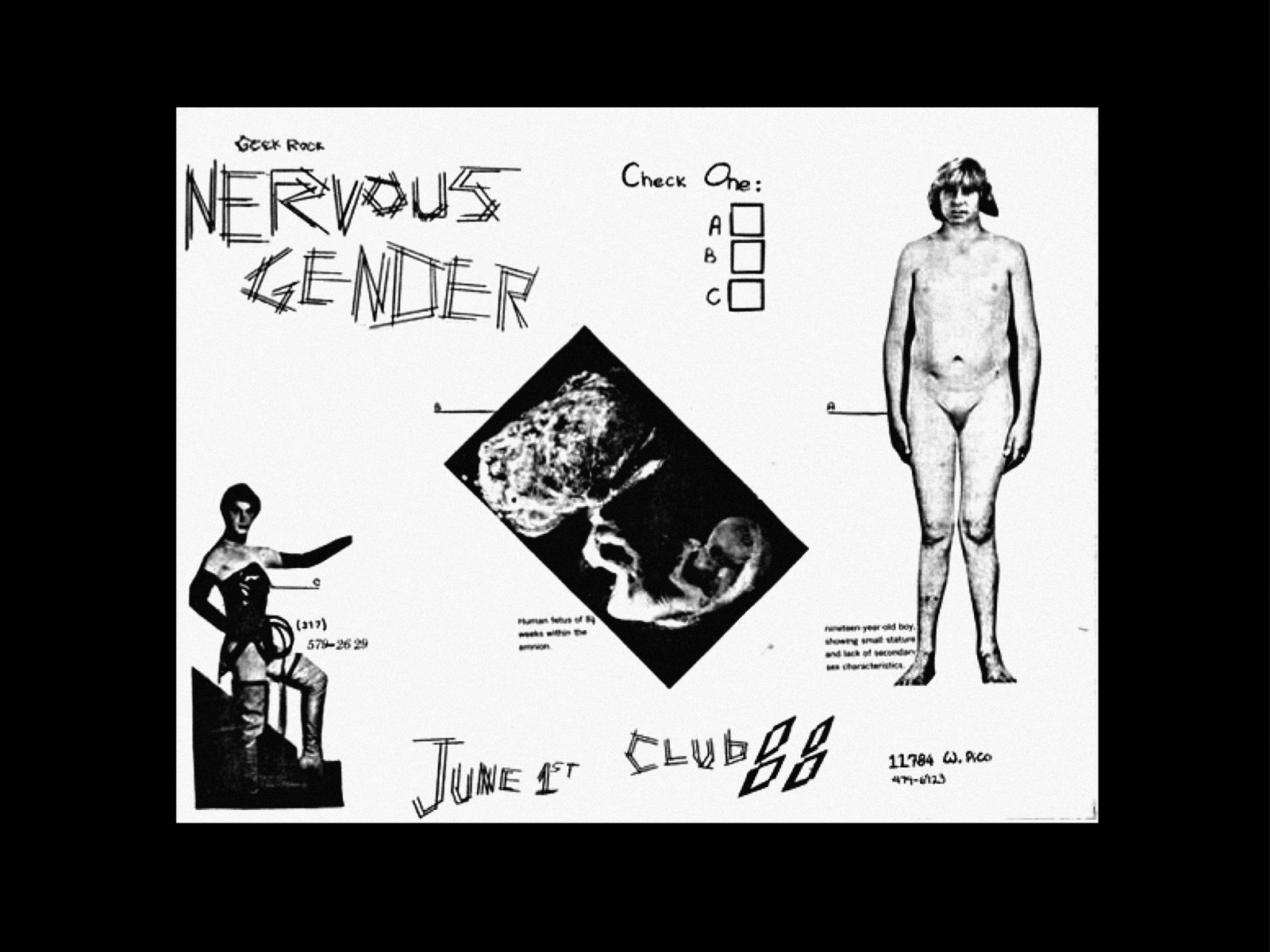

A Queer Year of Love Letters is a series of fonts that remembers the lives and work of countercultural queers of the past several decades. The fonts are an attempt to improvise a clandestine lineage, an aspatial and atemporal kind of queer kinship, through the act of writing. They are available to view and download for free on the open source platform Library Stack.

I want to remember something I never experienced. I want to remember Moonstorm and Tiamat Press. I’m attempting this with the help of digitized printed material, interviews, and other kinds of secondhand memory. I want to make this act of remembering accessible to other people, as easy as typing. Better yet: I want to make the act of typing an act of remembering. Enacted, remembering a past through the typing of new text extends that past and puts it to new work. We can call this memory-work. I want to remember with you.

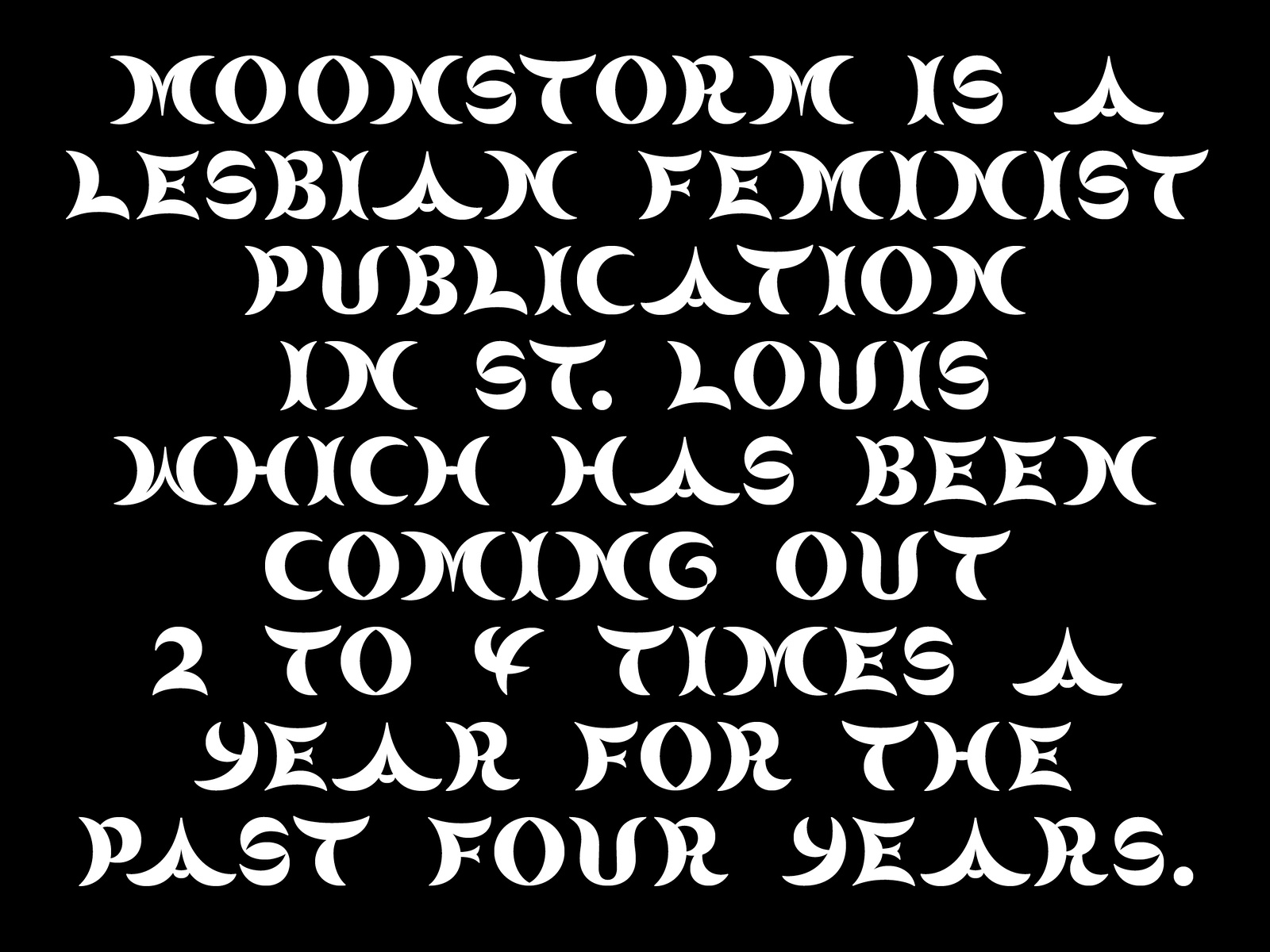

Tiamat Press was a publishing house organized by the Lesbian Alliance, a lesbian-feminist collective formed in St. Louis, Missouri, in the early 1970s. The Alliance provided communal resources to women in the form of an auto-repair shop (documented in a font called Women’s Car Repair Collective), a coffee house, a bookstore, and counseling and legal services, among other initiatives. Aside from offering printing, typesetting, and pamphlet production, Tiamat Press also published Moonstorm, a semi-frequent newsletter that served as a vehicle for lesbian-feminist-socialist theory and praxis. Its distribution throughout St. Louis increased visibility of the Alliance and functioned as a beacon for other lefty lesbians seeking like-minded fellowship.

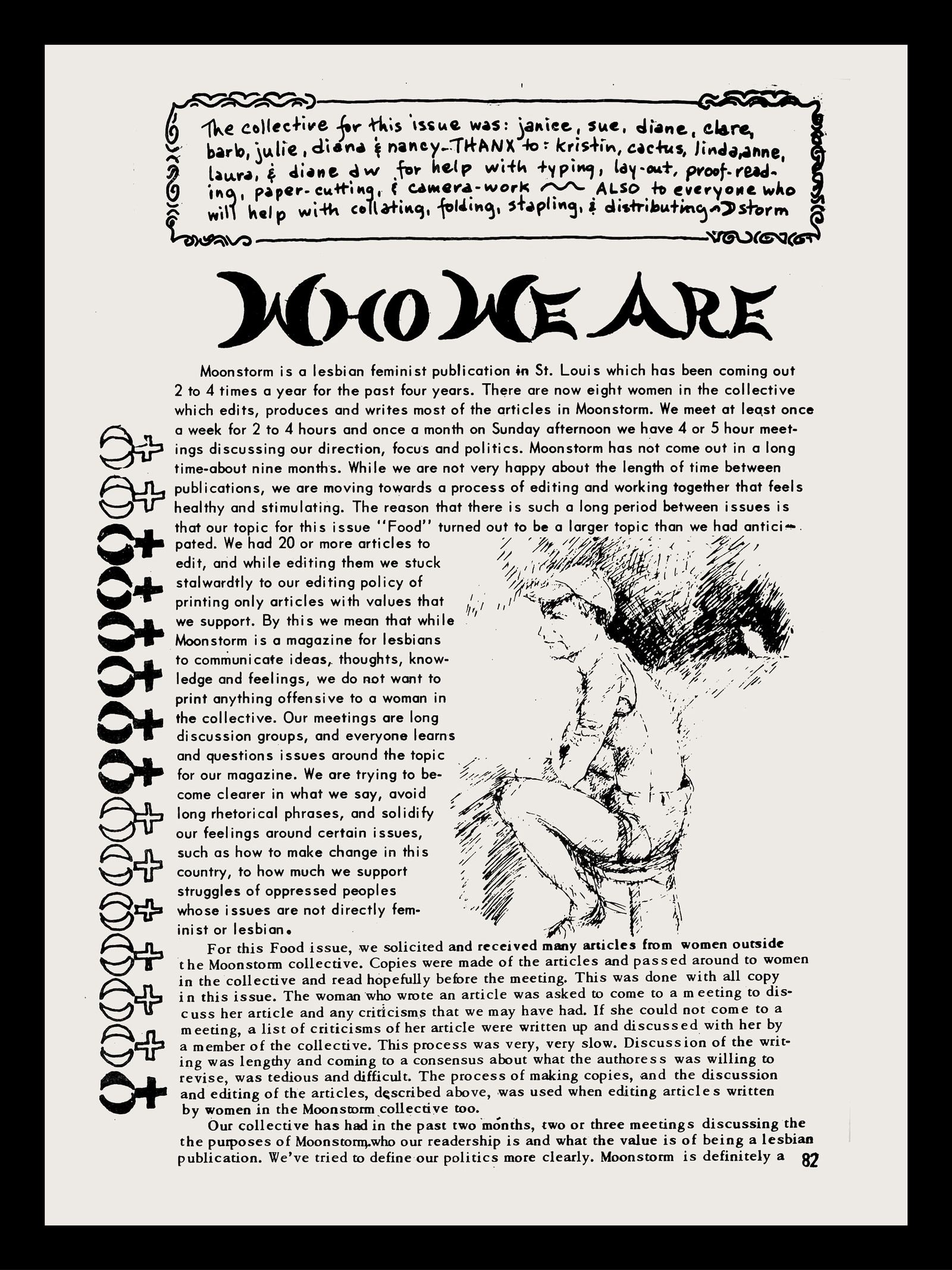

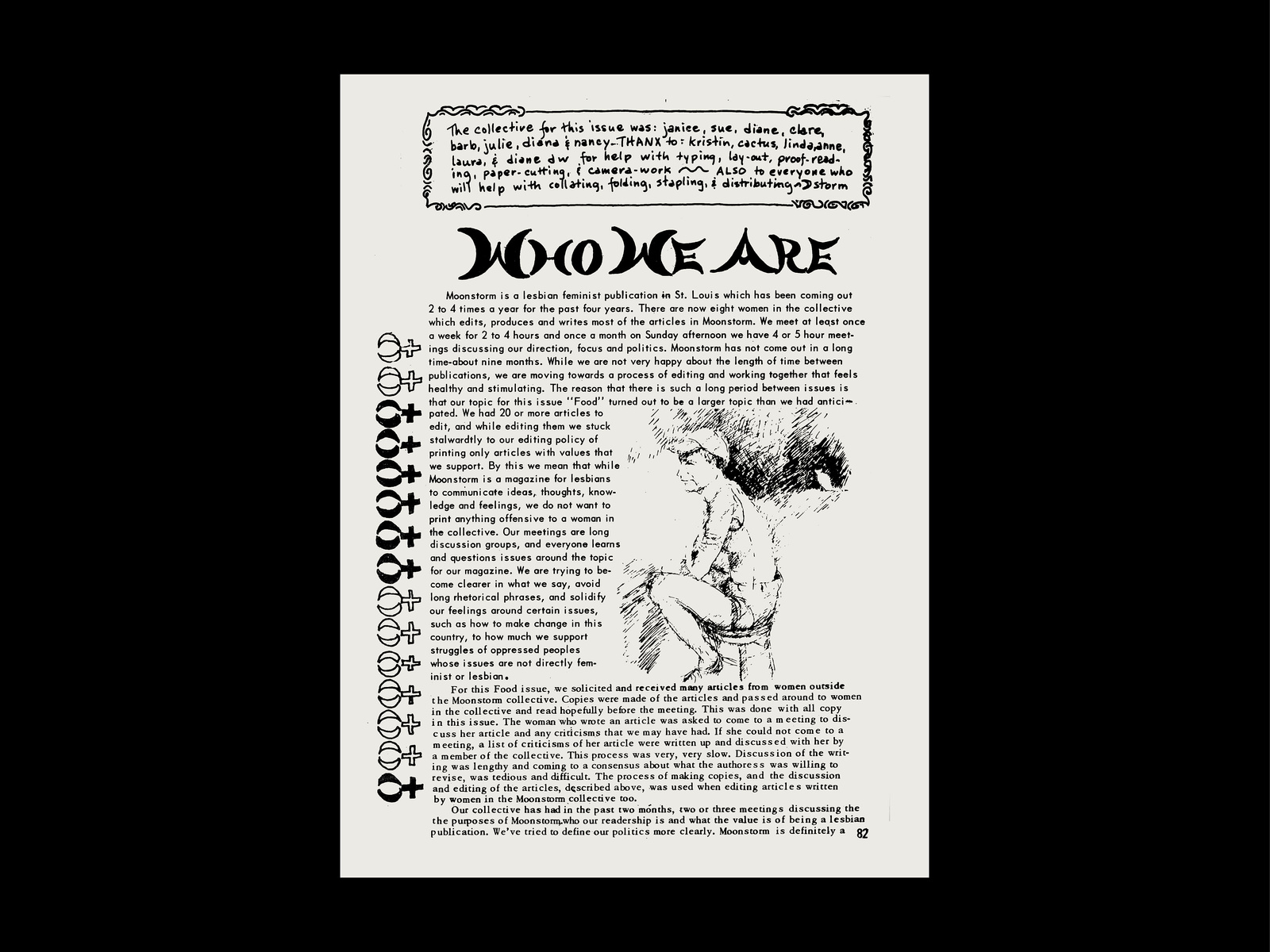

Beyond kinship through publishing, Moonstorm aspired to more radical aims: to transform the attitudes and power dynamics of the broader public sphere. The editors say as much in the Spring 1977 issue of Moonstorm. “We are…committed to making change in this country for all people. Revolution is a huge change in which people in positions of power are shaken. We want to get out more information about where power is and who’s controlling it…What can women do to take more power into their own hands?” This statement is nested under a headline that reads “Who We Are” in a stylized crescent moon-shaped type treatment. It’s this specific treatment that we’ll utilize for our memory-work.

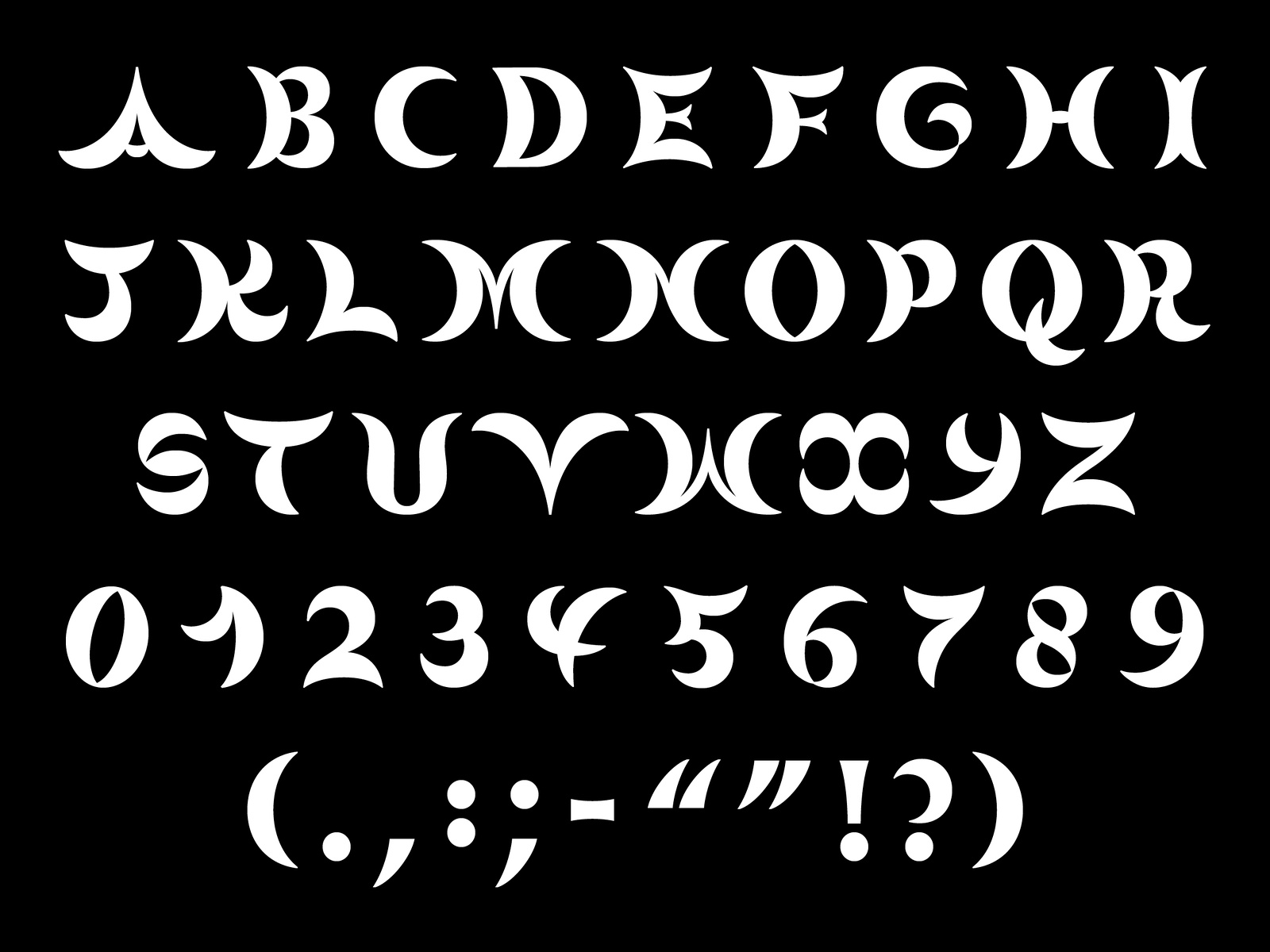

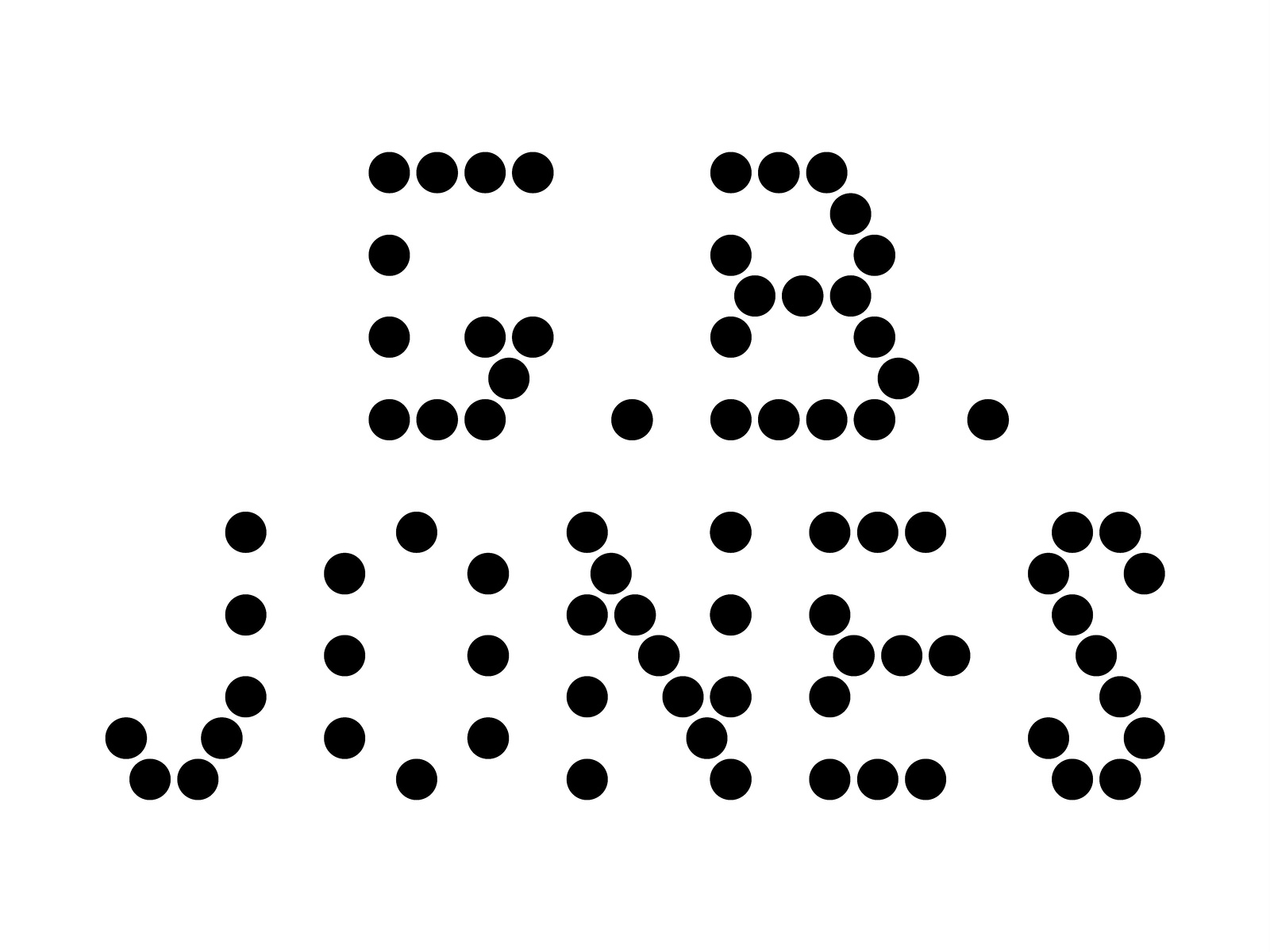

The crescent-shaped strokes of each letterform seem to nod to the name of the newsletter itself as they edge towards eclipse. I use these forms as the basis for a font, taking cues in order to fill in the gaps as needed. I use my imagination for some. I make the font quickly, I don’t second guess. I want to avoid delaying dissemination. As I make, it strikes me that the letterforms also look like a collection of boomerangs. The font acts like one too. The editors of Moonstorm lobbed their passions, positions, and politics out into the world. Now, through the Bézier curve of a typographic arc, we return to them and their work.

Statement from the editors of Moonstorm (Spring, 1977)

Robert Ford from A Queer Year of Love Letters

Women’s Car Repair Collective from A Queer Year of Love Letters

Martin Wong from A Queer Year of Love Letters

G.B. Jones from A Queer Year of Love Letters

Moonstorm from A Queer Year of Love Letters

Ernestine Eckstein from A Queer Year of Love Letters

Gerardo Velázquez from A Queer Year of Love Letters

The Spring 1977 issue of Moonstorm where we find these letterforms was dedicated to food justice in America. The issue was comprehensive, covering topics as varied as corporate agri-business, waitressing, food co-ops, government assistant programs, sterilization abuse, fat liberation, and the dangers of herbicides. It’s fitting then that this issue contains the letterforms that we’ll use for our memory-work. Food and text do similar things to bodies. Both share the ability to transform: in the case of food, the corporeal body; in the case of text, the body politic. In both cases, the body eats, or reads, and incorporates the outside world into itself. The food (the text) works in and on the body, shaping it, changing it. Moonstorm assumes this role of sustenance, and it means to nourish the body politic.

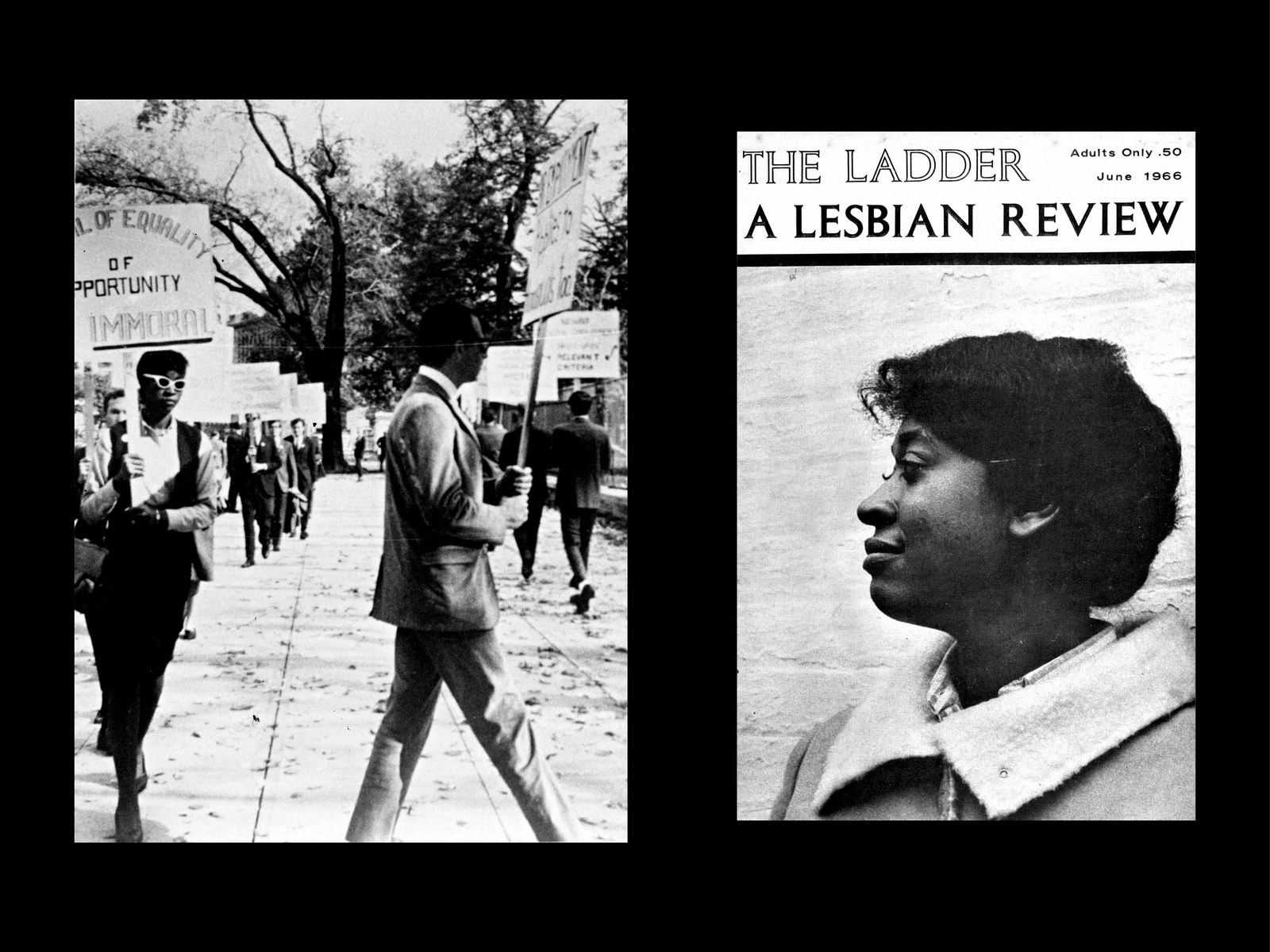

But the body is also a transformation apparatus. Eating and reading necessitate excreting and writing, which is to say a process of revolution. This is how Moonstorm nourishes: it induces new texts and new writing. It tasks its readers with rewriting the world. These readers (now writers) of new writing pick up where Moonstorm left off and redress what was left out. The editors of this issue—Janice, Sue, Diane, Clare, Barb, Julie, Diana, and Nancy—while eluding individual identification through the use of first names, acknowledged the shortcomings of their all-white collective: “We realize that we are a collective of eight white lesbians … No articles were written by Third World women, or Black women.” In taking up this unfinished work, Moonstorm’s reader-writers transform and revitalize it.

Moonstorm.otf, with its revolving forms, is a portable memory unit. It remembers Moonstorm in its formal expression and contains information about its origins in its metadata. It remembers this lesbian-socialist history even if its users do not. As users type they reproduce this history and put these forms to new work. We type and we remember, ever tilting towards the not-yet.

Various covers of Moonstorm (1973–1977)