The Visual Language of Dance Notation

It’s easy to forget that information is material. Even though digitally produced texts are generated, stored, and transmitted through physical objects, chemical processes, and energetic exchanges; even though written language makes meaning through concepts grounded in embodied experience. Yet, the steady march of progress in the history of the production of written texts, from the obvious physical involvement of medieval scribes laboring over an illuminated manuscript to the apparent disembodiment of a website’s text and images, has continually disavowed the physical experience of writing, reading, and copying. Notational systems for dance, examples of which date back to at least the 15th century, however, stand out in their ability to force us to reckon with the philosophical conundrum of the binary of body and mind. These reveal more obviously that a body or some physical matter is already always implicated in writing and reading.

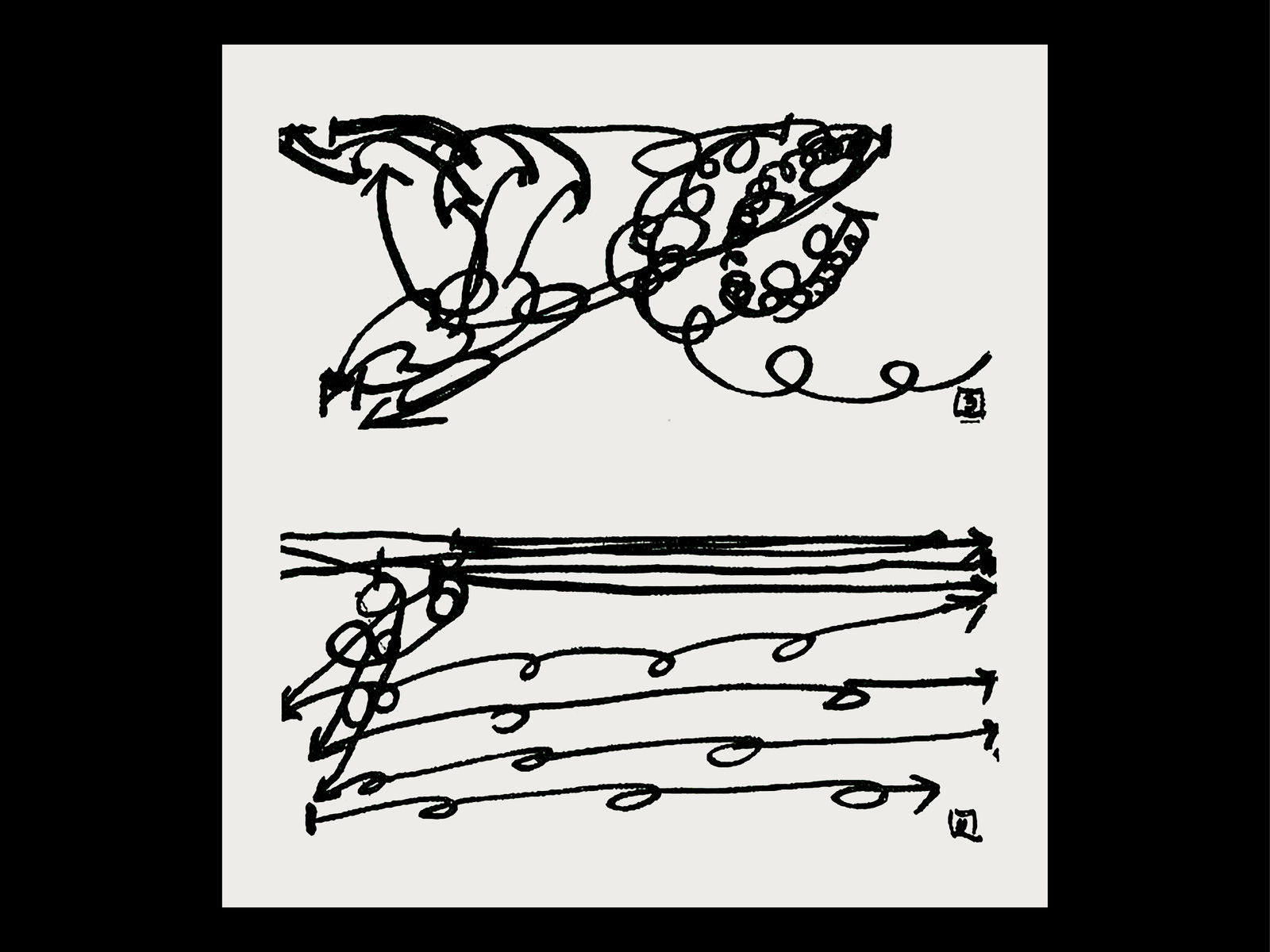

Merce Cunningham, Summer space (1958)

Lucinda Childs, Melody Excerpt (1977)

Merce Cunningham, Aeon (1961/1963)

Simone Forti, Score for Face Tunes (1967)

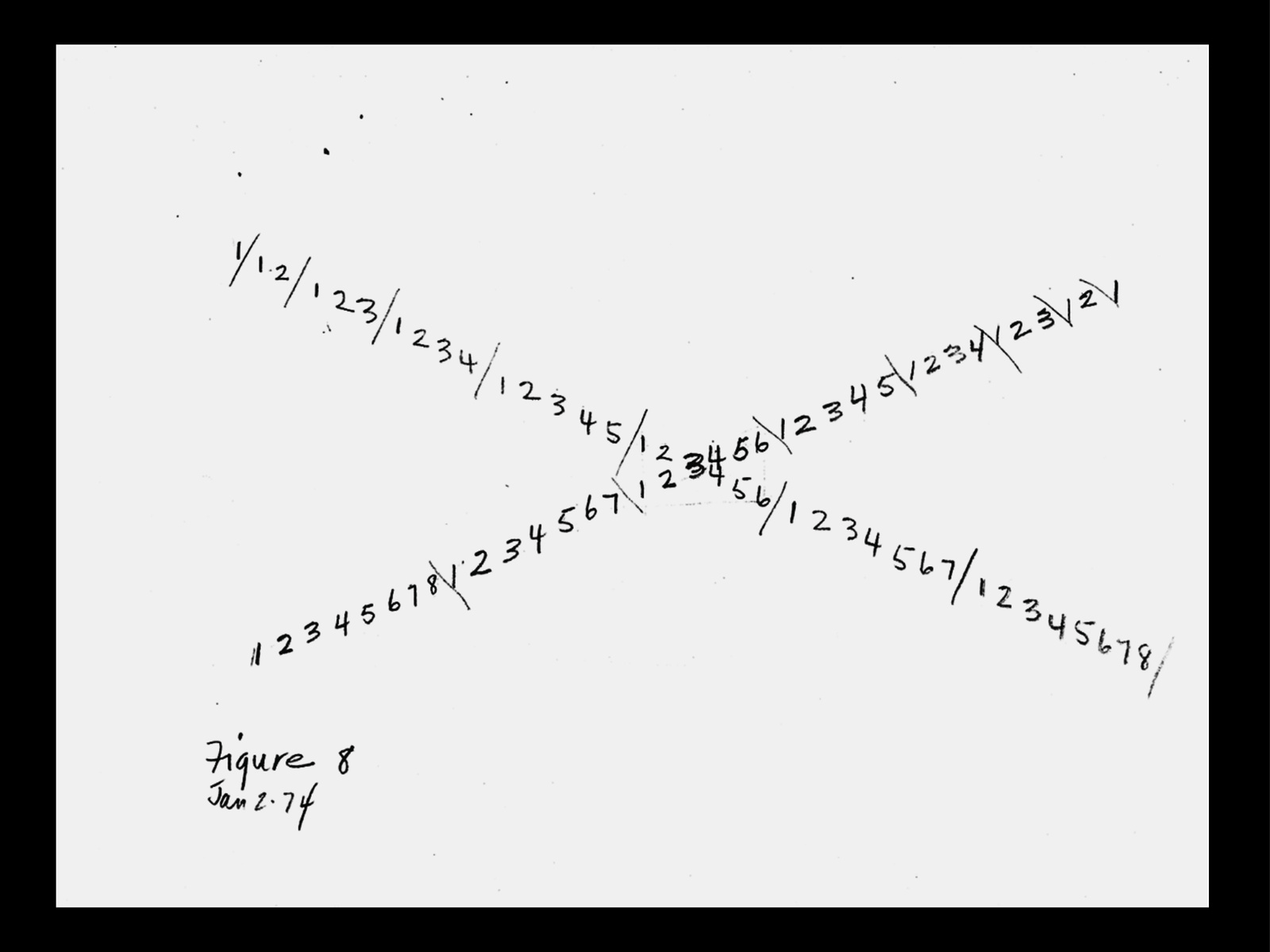

Trisha Brown, Figure 8 (1974)

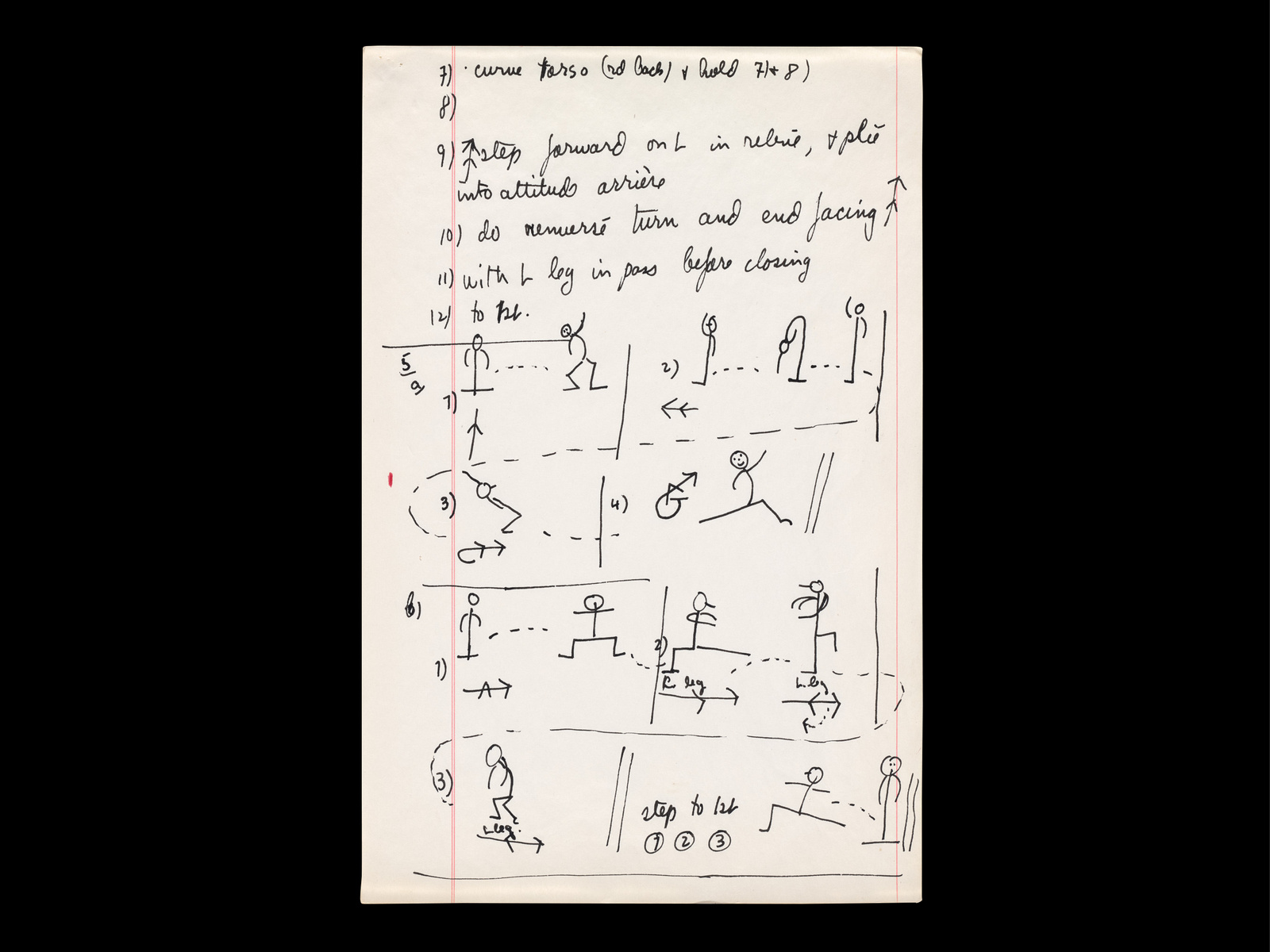

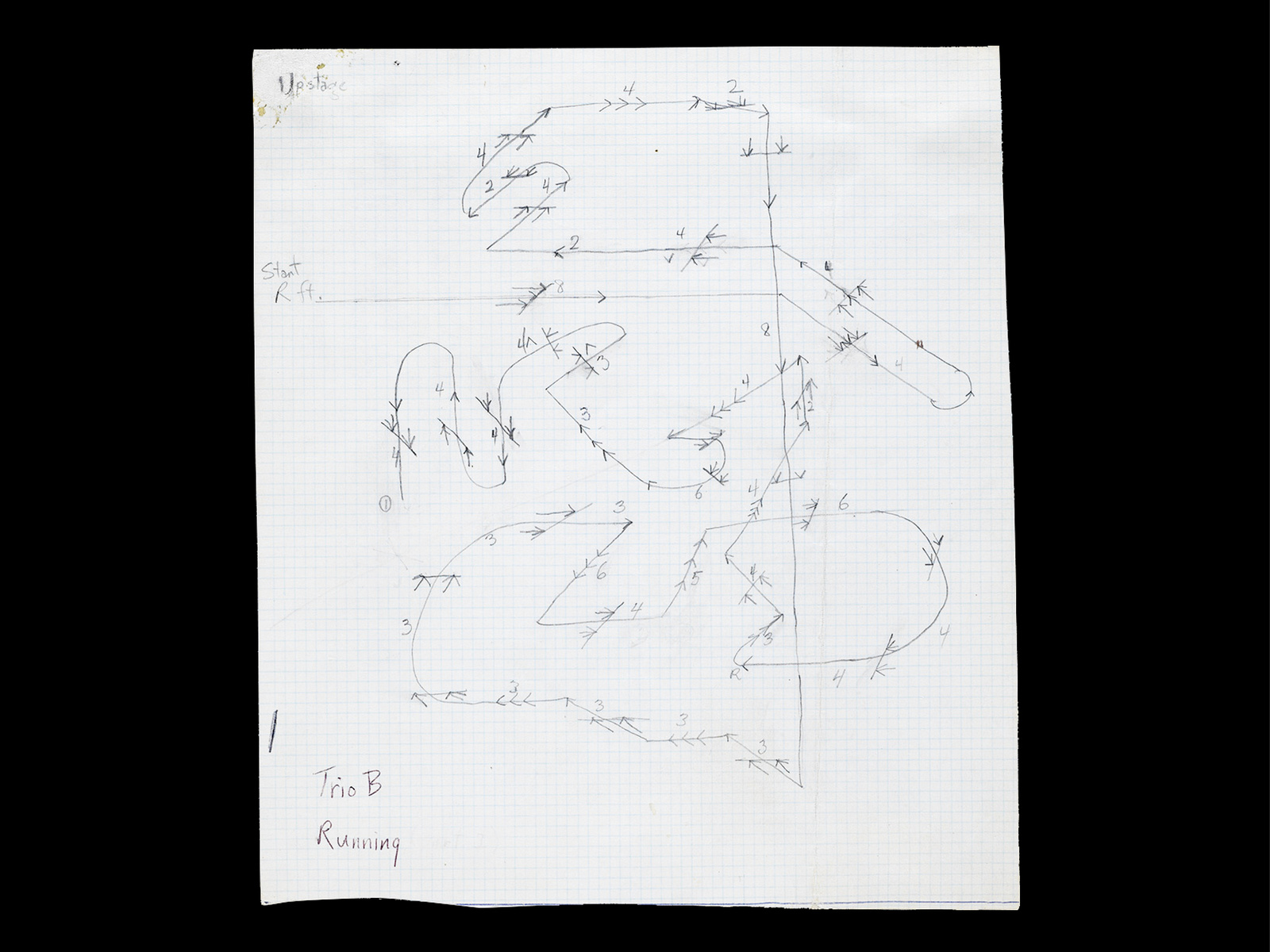

Yvonne Rainer, Trio B: Running from The Mind Is a Muscle (1966–68)

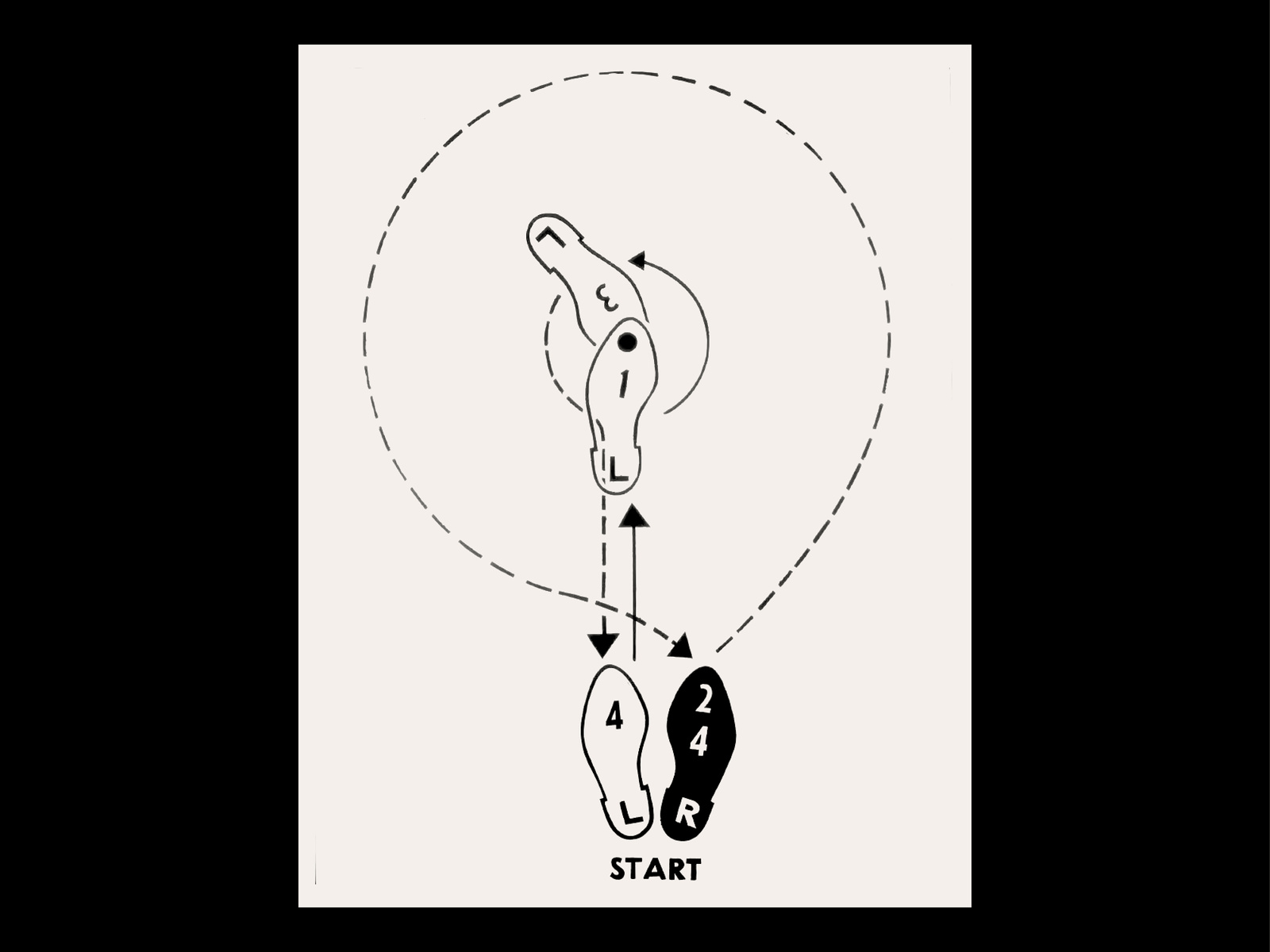

Andy Warhol, Dance Diagram 3, The Lindy Tuck-In Turn-Man (1962)

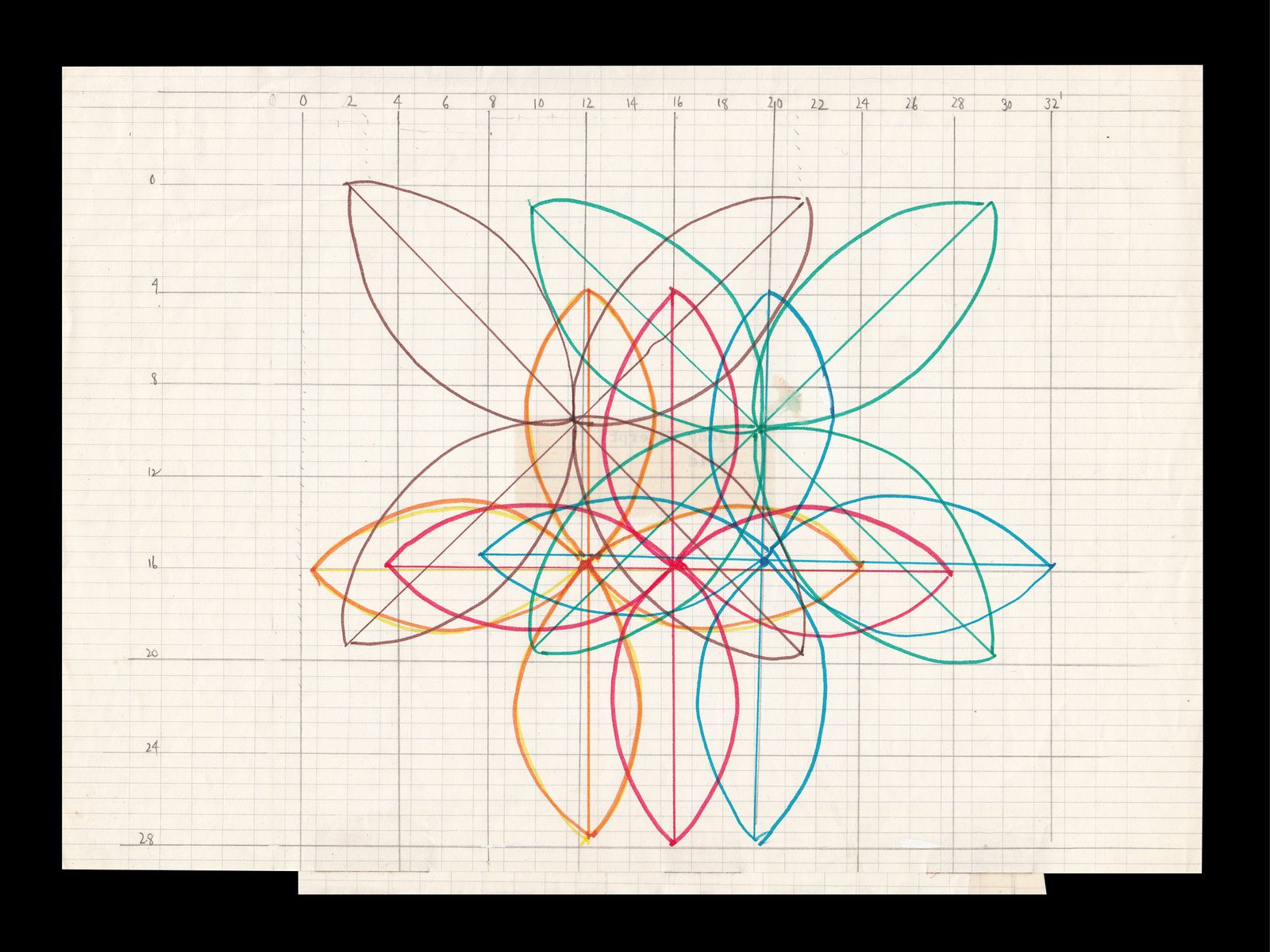

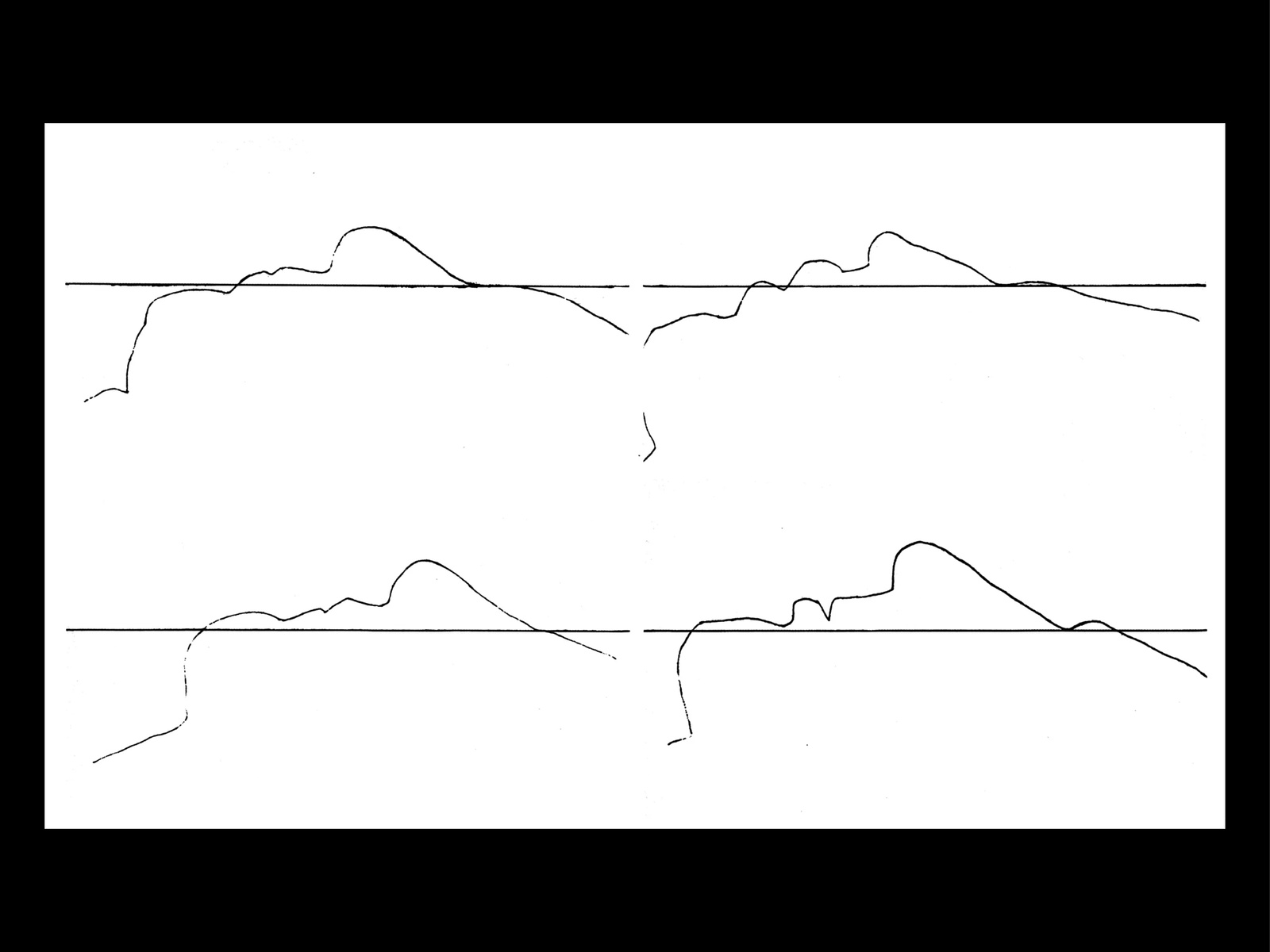

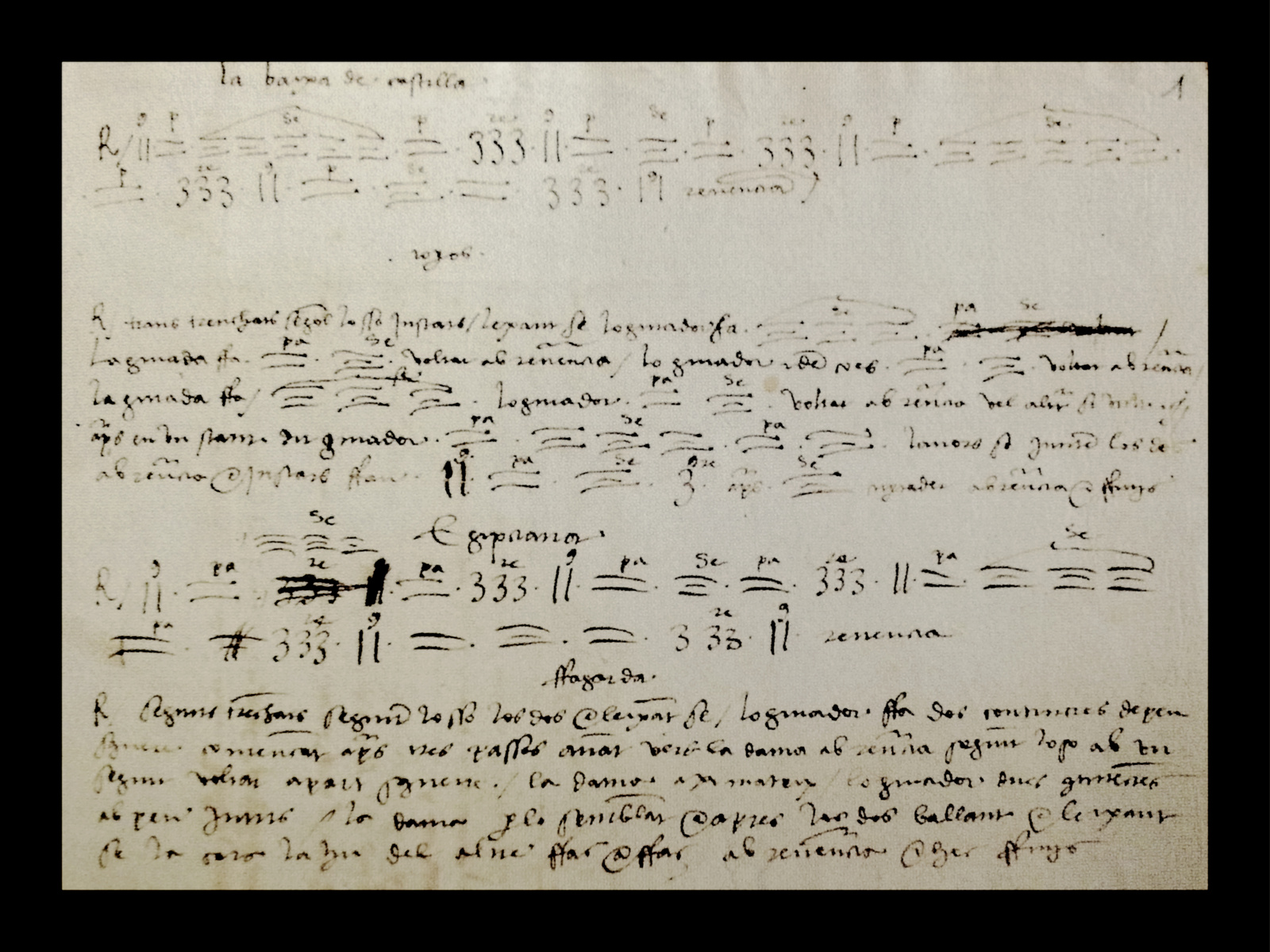

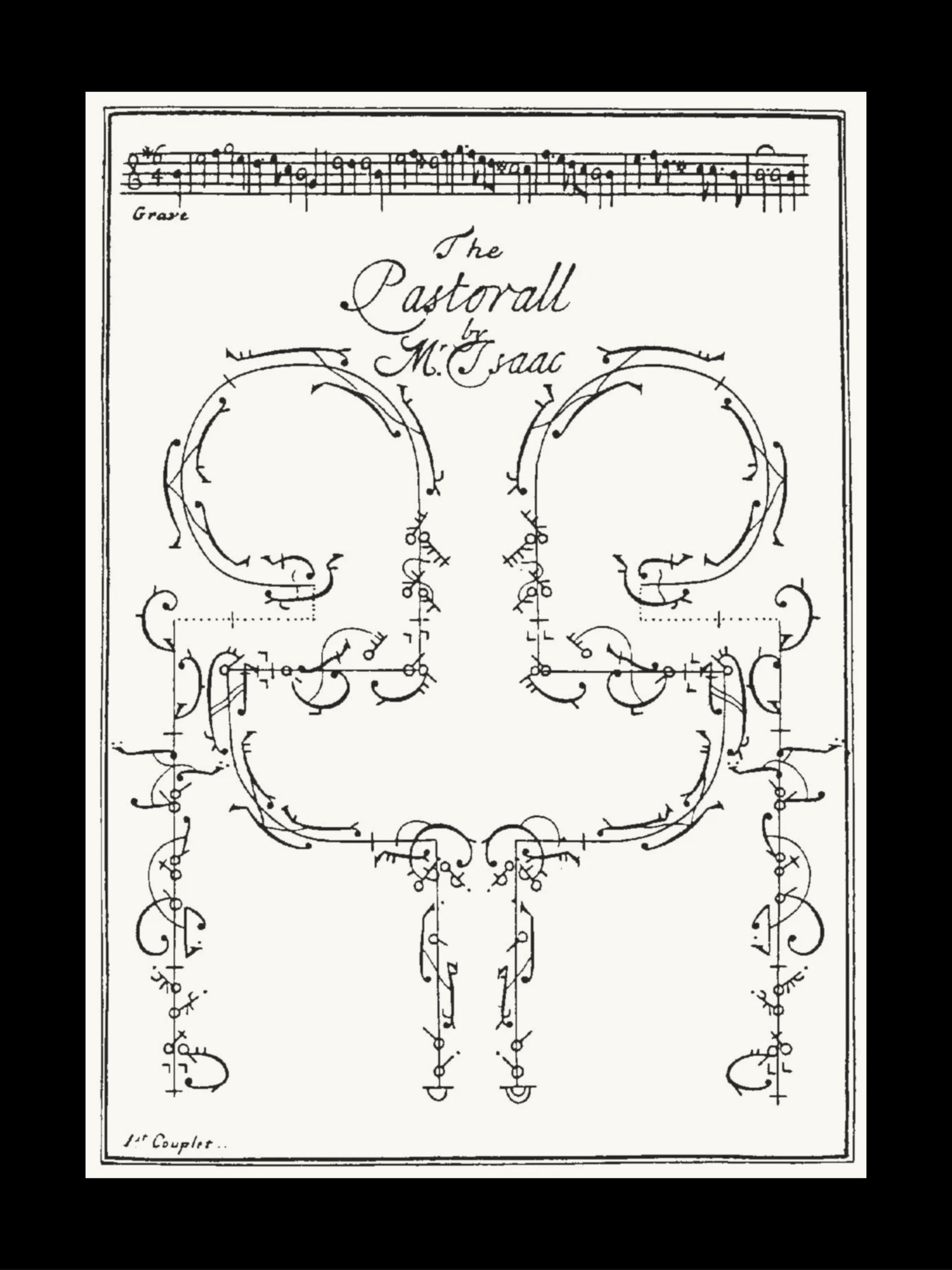

There have historically been countless ways of representing dance on paper in symbols, words, or images. These have existed for analysis and preservation but also for movement inspiration and generation, as in the case of the idiosyncratic notation of artists like Merce Cunningham, Lucinda Childs, Trisha Brown, and Simone Forti (to name a few). Movement notation systems throughout history are culturally situated, shaped by the needs, intentions, and aesthetics of their writers and intended readers. Many early systems depended on a reader’s contextual knowledge of codified steps. The 15th-century Cervera manuscript, for example, uses words and abbreviations for the names of steps. In Baroque Feuillet notation, ornate swirls follow the dancer’s track through space from a bird’s-eye view.1Ann Hutchinson Guest, Choreo-Graphics, (New York, London: Gordon and Breach, 1989) 3; Victoria Watts, “Archives of Embodiment: Visual Culture and the Practice of Score Reading.” In Dance on Its Own Terms, ed. Melanie Bales and Karen Eliot (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) 363-388. Stepanov notation of the 19th century also depended on contextual knowledge, in its case of the classical ballet conventions of imperial Russia. Tracks follow a dancer’s path through space, but the system also offered the innovation of an anatomically-based recording system.2Sheila Marion and Karen Eliot: “Recording the Imperial Ballet: Anatomy and Ballet in Stepanov’s Notation,” in Dance On Its Own Terms, eds. Melanie Bales and Karen Eliot (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) 308-340.

Cervera manuscript (15th century)

In the 20th century, systems of dance and movement notation proliferated and competed. The rise of dance notation was sparked by the New Dance movement of Weimar Germany, whose proponents wanted to forge an independent, expressive art form with its own theory and language to break free from the inherited tradition of classical ballet.3Vera Maletic, Body, Space, Expression: The Development of Rudolf Laban’s Movement and Dance Concepts. (Berlin; New York; Amsterdam: Mouton de Gruyter, 1987). Rudolf Laban, the foremost choreographer, teacher, and theorist of expressionist dance, visualized his ideas with angular geometric symbols aesthetically influenced by Bauhaus design.4Watts, “Archives of Embodiment.”

Laban published an early version of his notation system in Alfred Schlee’s periodical Schriffttanz (Script Dance) in 1928.5Rudolf Laban, Schrifttanz (Vienna, Leipzig: Universal Editions, 1928). In subsequent decades, notators around the world developed and standardized Laban’s system. Others, Margaret Morris, Sol Babitz, Rudolf and Joan Benesh, Noa Eschol and Abraham Wachman, Alwin Nikolai, and Eugene Loring, for example, created their own symbology. Each creator competed to make their system the new common language of dance. From the many contenders, Benesh Movement Notation, Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation, and Laban’s system (that came to be known in the United States and England as Labanotation and in Europe as Kinetography Laban), dominated the field at mid-century.6Of these, Benesh Movement and Labanotation are the current standards for dance preservation. Libby Smigel, Martha Goldstein, Elizabeth Aldrich, Norton Owen, and Barbara Drazin, “Documenting Dance: A Practical Guide,” (Washington, D.C.: Dance Heritage Coalition, 2006.) Labanotation found particular success in the United States due to a small group of mostly volunteer female dance notators working under the auspices of a New York City organization called the Dance Notation Bureau (DNB).7https://www.dancenotation.org The DNB integrated the notation into the major festivals of modern dance, integrated it into choreographic copyright, and recorded many theatrical dances with it. They promoted Labanotation for use in ethnographic studies of dance, psychology, and industry, and their work helped lay foundations for the formation of new academic fields of dance studies and dance technology.

Baroque Feuillet notation used for The Pastorall: Mr. Issac’s new dance made for Her Majestys birth day 1713 (1713)

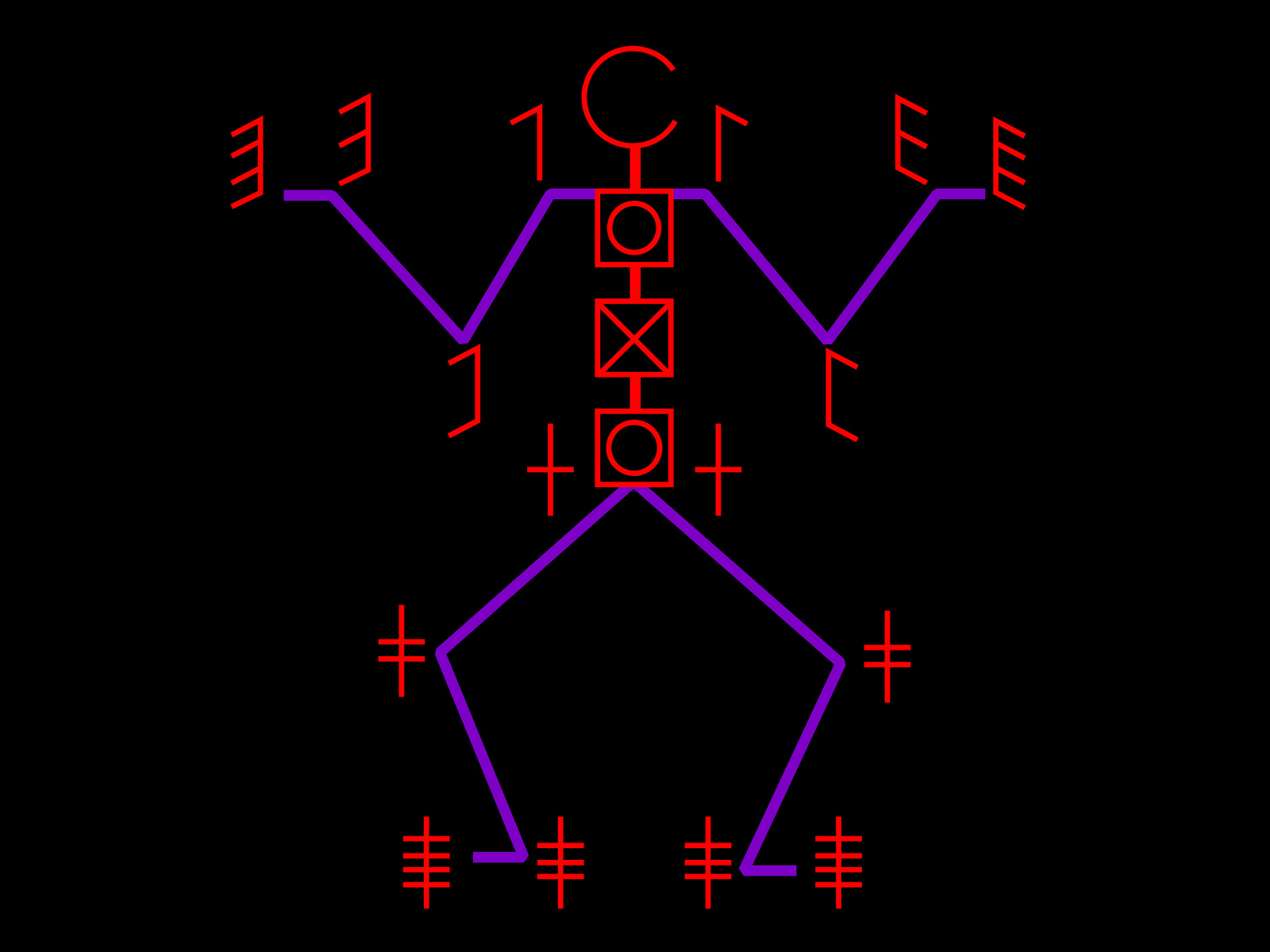

Labanotation signs for parts of the body

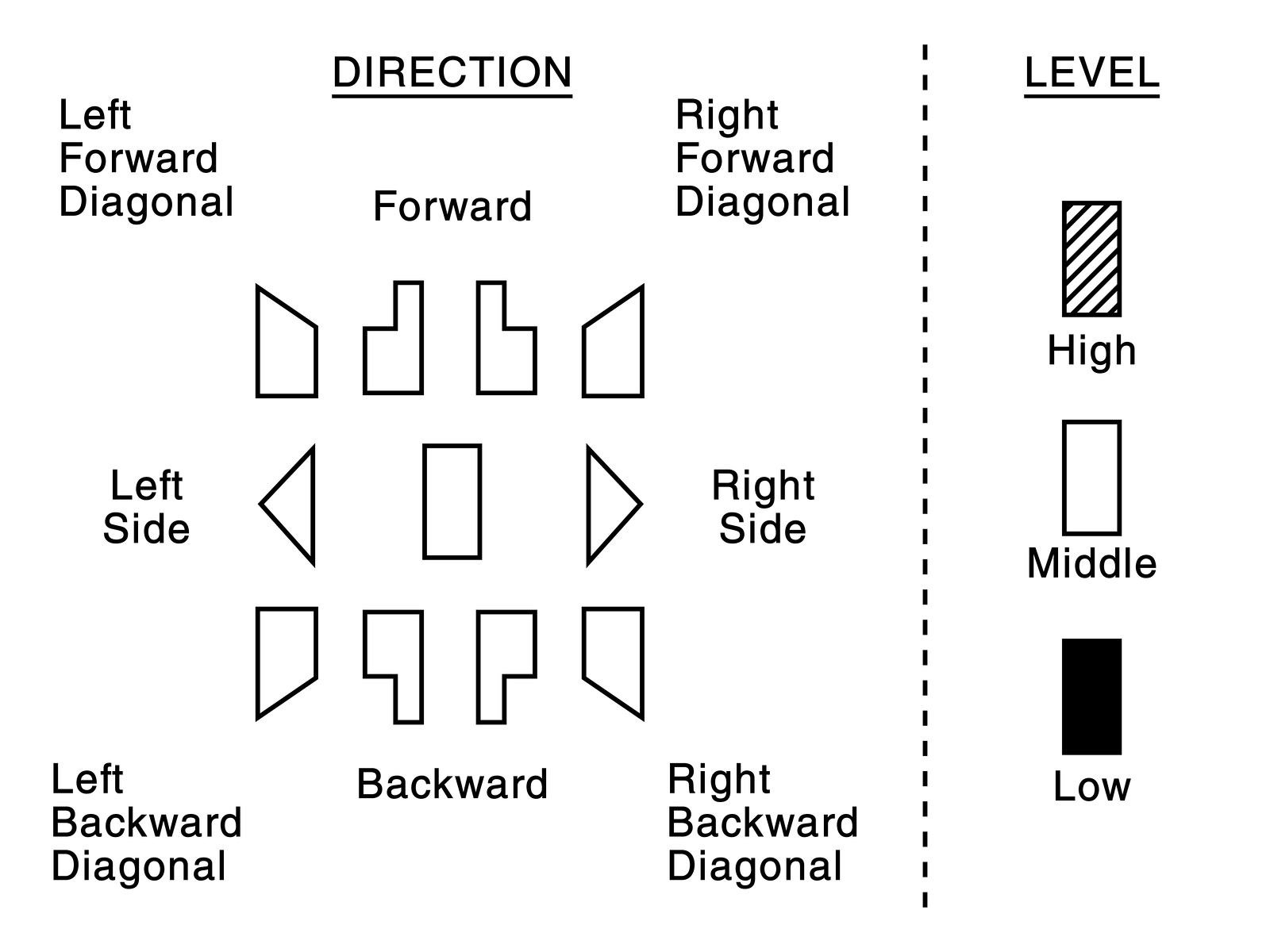

Basic signs and patterns of Labanotation

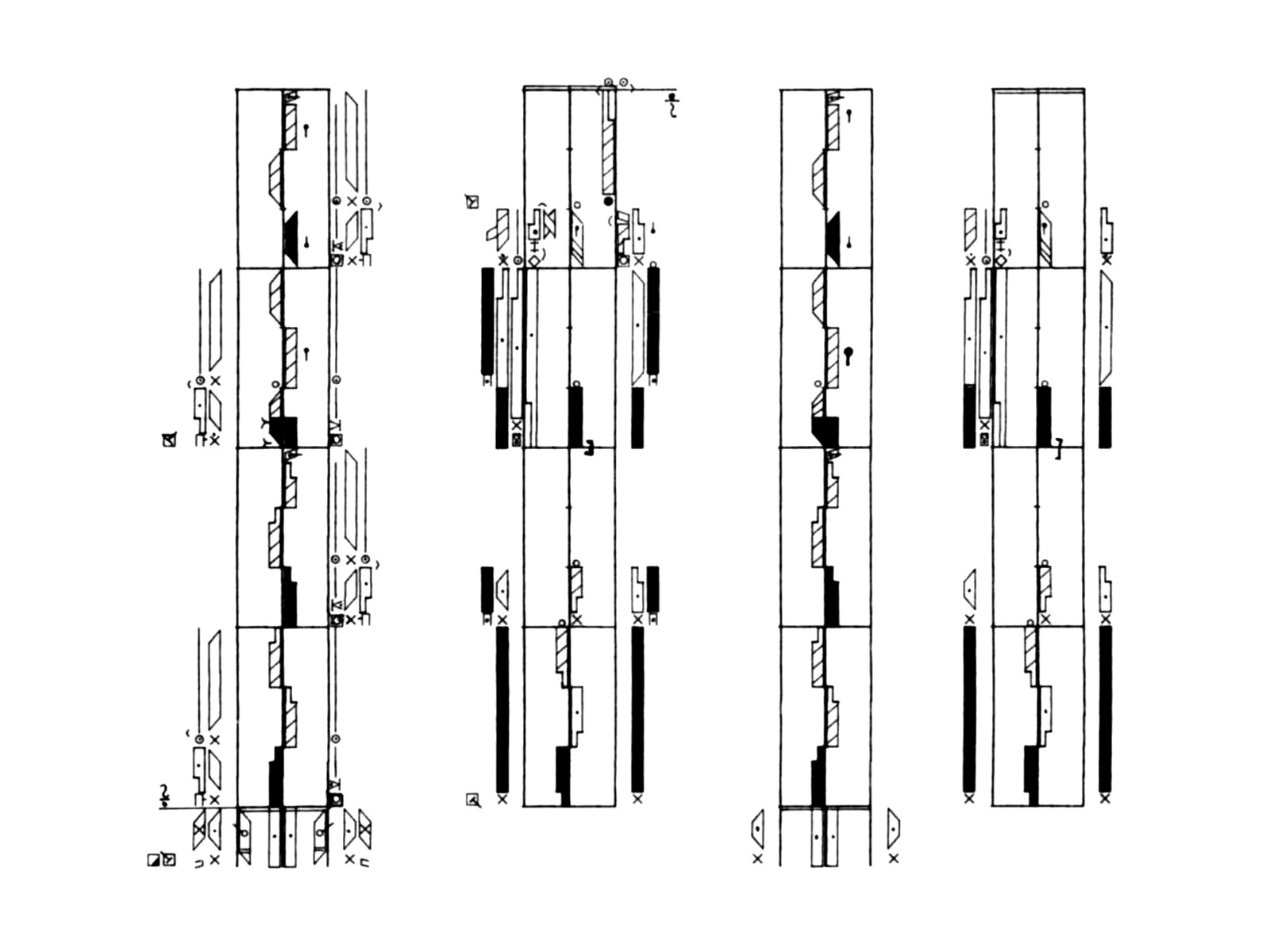

Score for performance using Labanotation

LEFT: Labanotation score of Passacaglia and Fugue, Labanotation by Lucy Venable (1954–1955), Choreography by Doris Humphrey (1938). RIGHT: Page from Beiträge zur Orthographie von Bewegungen by Albrecht Knust shows an example the aniline dye used in spirit duplication (c. 1932). Images courtesy of the Dance Notation Bureau and The Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Institute, the Ohio State University

Benesh Movement Notation

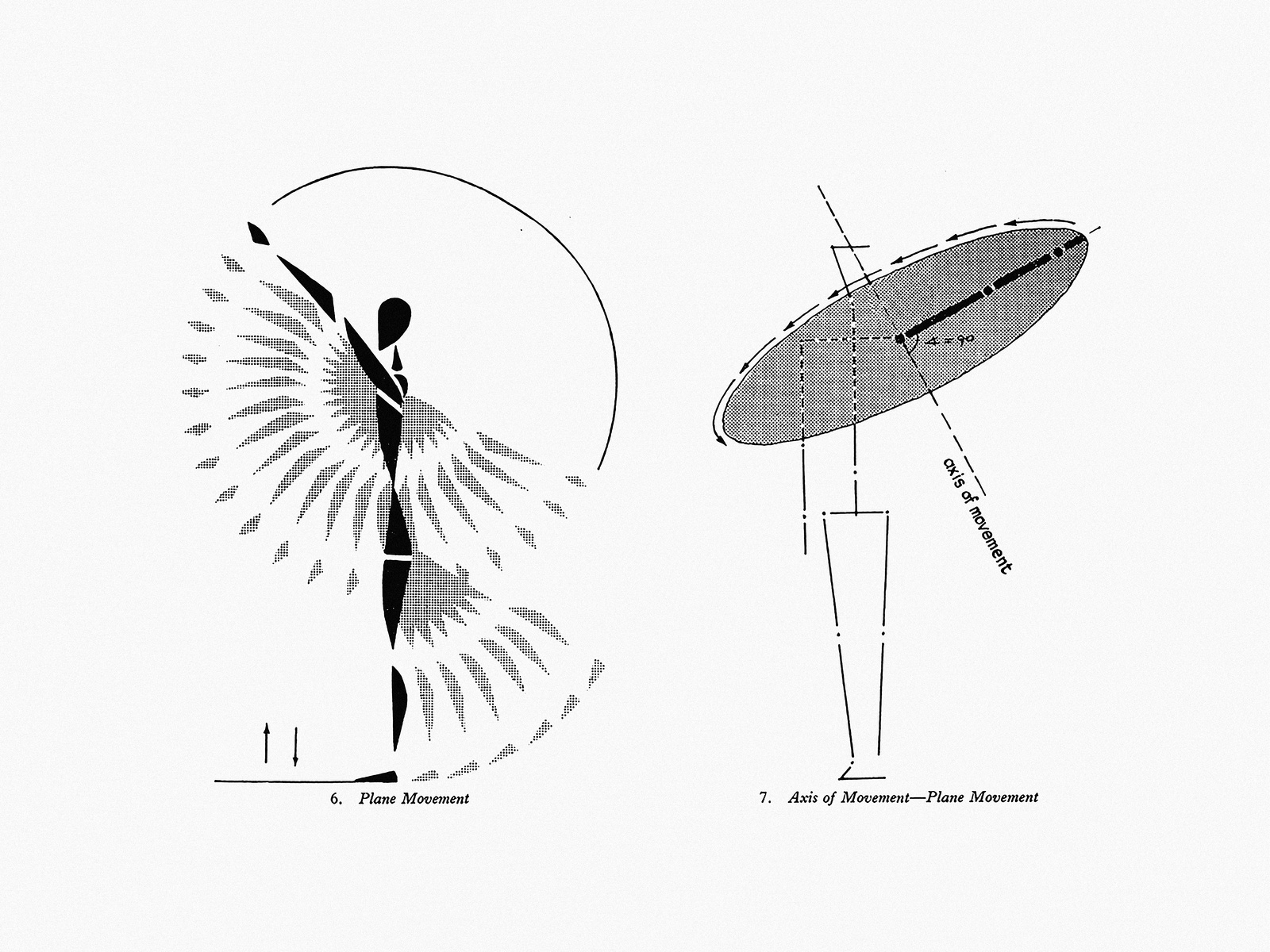

Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation

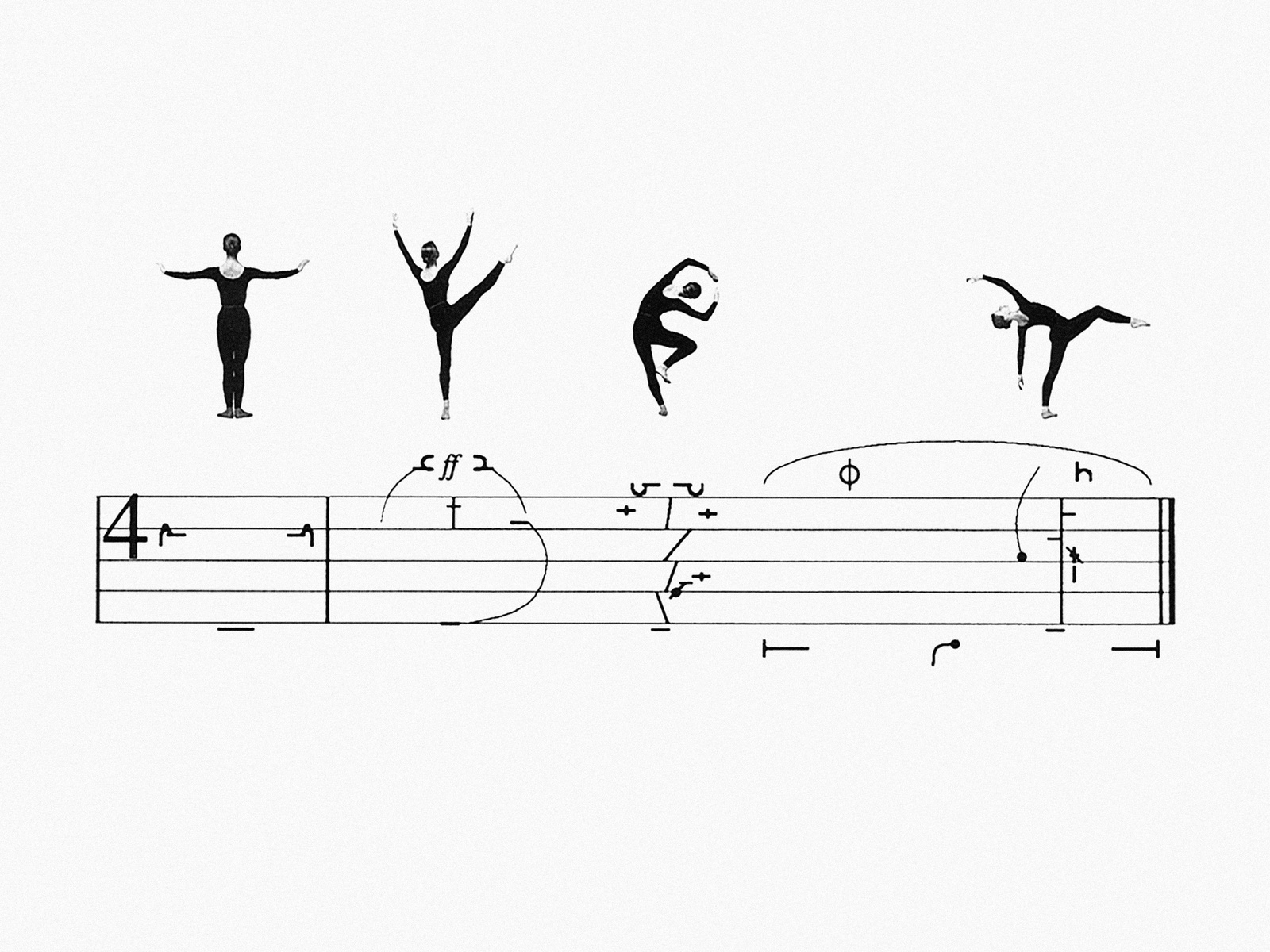

Labanotation denotes robust movement information. It is organized in terms of body anatomy, space, and linear time on a five-line staff read from the bottom of the page to the top. Labanotation allows the writer to break down the fleeting phenomenon of movement into parts and record movement in detail.8Ann Hutchinson Guest, Labanotation: The System for Recording and Analyzing Movement, 4th edition, (New York, Routledge, 2005). Just as a symphonic score records each voice in an orchestral ensemble, a Labanotation score can record each dancer’s movements and paths through space, thereby offering a repeatable record of an entire work of choreography. As a dancer, curator, and Labanotation practitioner, I have experienced firsthand how the use of Labanotation facilitates dance preservation and transmission and nurtures creativity both individually and communally.9Mara Frazier, “Labanotation is Creative,” Journal of Movement Arts Literacy 7, no. 12, 2021: 105-131. I’ve recently become interested in not only how Labanotation mediates dance and movement information, but in the wide variety of production and reproduction techniques historically used in Labanotation’s material texts.

Though Whitney E. Laemmli claims that Labanotation “consigned the three-dimensional experience of movement to the two-dimensional page,” effectively disembodying dance, I disagree.10Whitney E. Laemmli, “Paper Dancers: Art as Information in Twentieth-Century America.” Information & Culture 52, no. 1 (February 2017): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.7560/IC52101. It is my experience that in fact, Labanotation infuses the process of reading and writing with embodiment. Labanotation texts, after all, are made to be enacted by a body. Not only that, but we physically interact with the materials on which all texts are printed. Extant Labanotation texts take on a variety of formats, and like other twentieth century documents, they have been produced using a panoply of technologies. Some texts of Labanotation, emphasizing the unusual fact that reading and writing Labanotation nearly always necessitates actual movement, require embracing odd formats. These include movable floor tiles and large-format wall scrolls that were used by early Labanotation instructors to provide hands-free reading for students.

Ann Hutchinson Guest using floor tiles while teaching Labanotation (c. 1954). Courtesy of the Dance Notation Bureau and The Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Institute, the Ohio State University.

Other Labanotation texts look a little more familiar; they are on paper; they were produced and copied either by hand, mechanically, or digitally. Handwritten manuscripts required notators to use “a pencil, compass, and ruler” and write on large-format graph paper.11Lucy Venable, “LabanWriter: There Had to Be a Better Way,” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 9, no. 2, 1991: 76. Those deemed most valuable were copied neatly in India ink by autographers—trained notator/artists with a steady hand. Some dance notation scores were spirit duplicated in aniline dyes––byproduct of coal production––rendered in brilliant mauves, purples, greens, reds and yellows.12In the United States this is more commonly known by the commercial term, “Ditto,” or in Europe, “Banda.” Simon Garfield, Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color that Changed the World, (New York: Norton) 1992. Rich Dana, Cheap Copies: The OBSOLETE PRESS Guide to DIY Hectography, Mimeography, and Spirit Duplication (Coralville, Obsolete Press). Or they were mimeographed.13Because symbols were written on wax mimeograph masters with a stylus, the notation was simplified, limiting the technical complexity of the notation. As mimeograph was the most affordable option for organizational newsletters and class worksheets, expressions of Labanotation in these formats were severely constrained by the technology. Scores were also Thermofaxed, Xeroxed, blue printed, and Diazotyped.14Not an exhaustive list; Brian Cassidy’s Rare Book School course, “Identifying and Understanding Twentieth Century Duplicating Technologies,” helped greatly in my identification of these technologies from the materials in the Dance Notation Bureau Collection, The Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Institute, Thompson Library Special Collections, The Ohio State University Libraries.

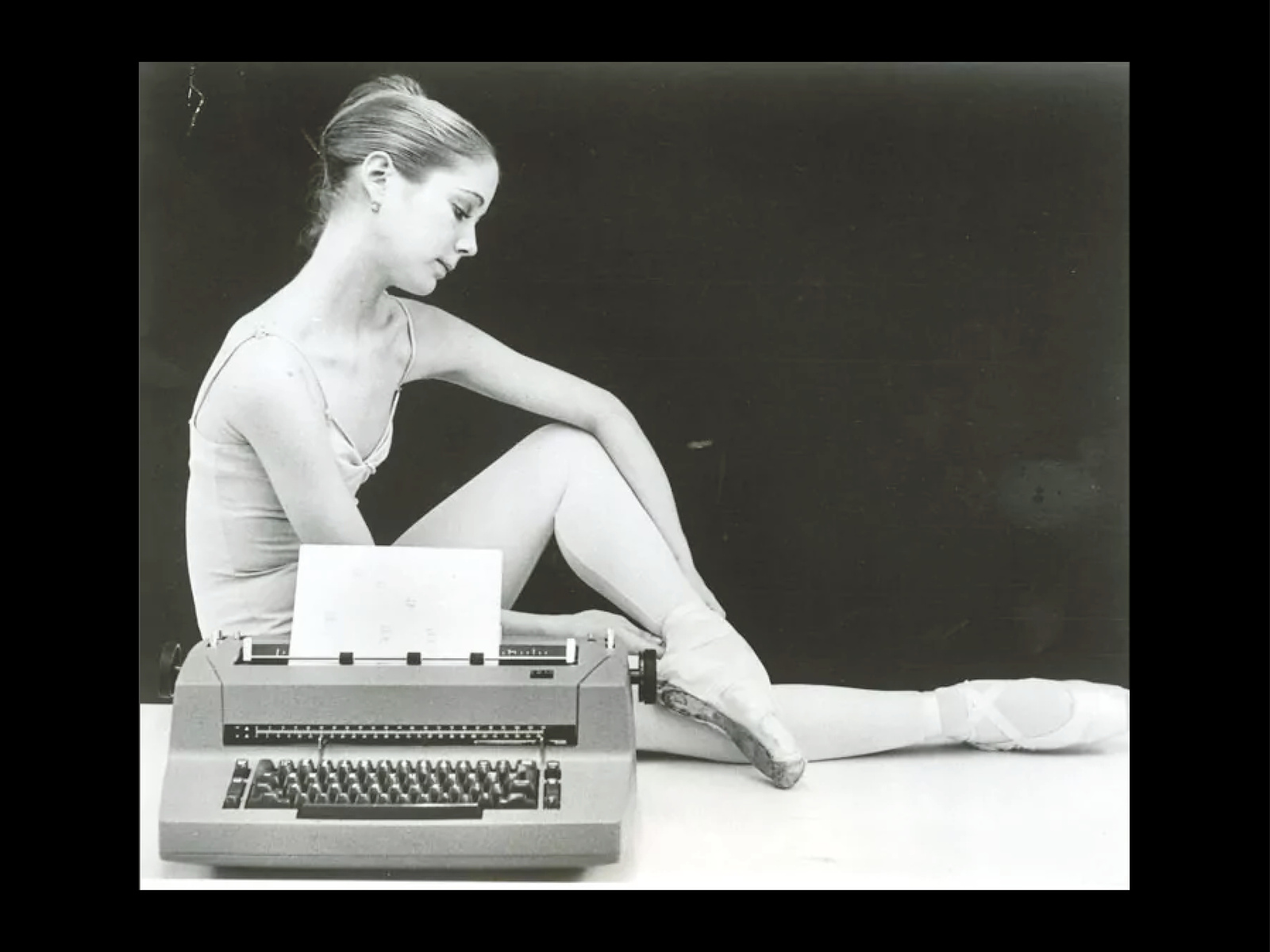

In the United States, the labor of producing and reproducing scores was predominantly done by women often working as volunteers under the auspices of the Dance Notation Bureau. These notators struggled to make their craft into a paid profession. Thus, they continually searched for a way to produce scores neatly and efficiently with a production method that looked technical and scientific enough to garner respect. They found their solution in the popular IBM Selectric Typewriter.

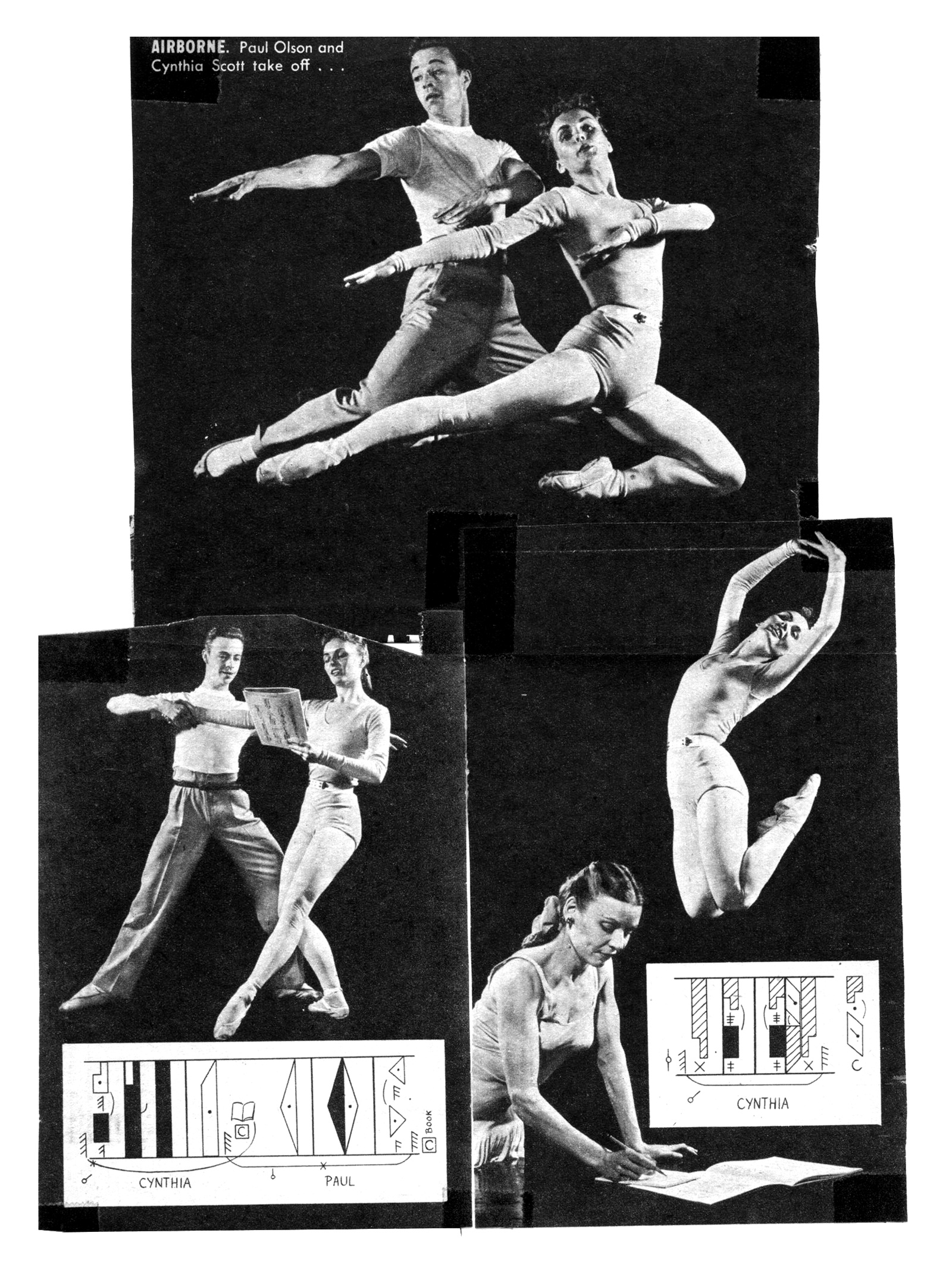

Ann Hutchinson notating Paul Olsen and Cythia Scott (n.d.)

IBM, Innovation to the Dance (1973)

IBM, Typewriter for the Dance (1973)

IBM Selectric Typewriter (1961)

Instruction Manual For Use With The Labanotation the IBM Selectric (1974)

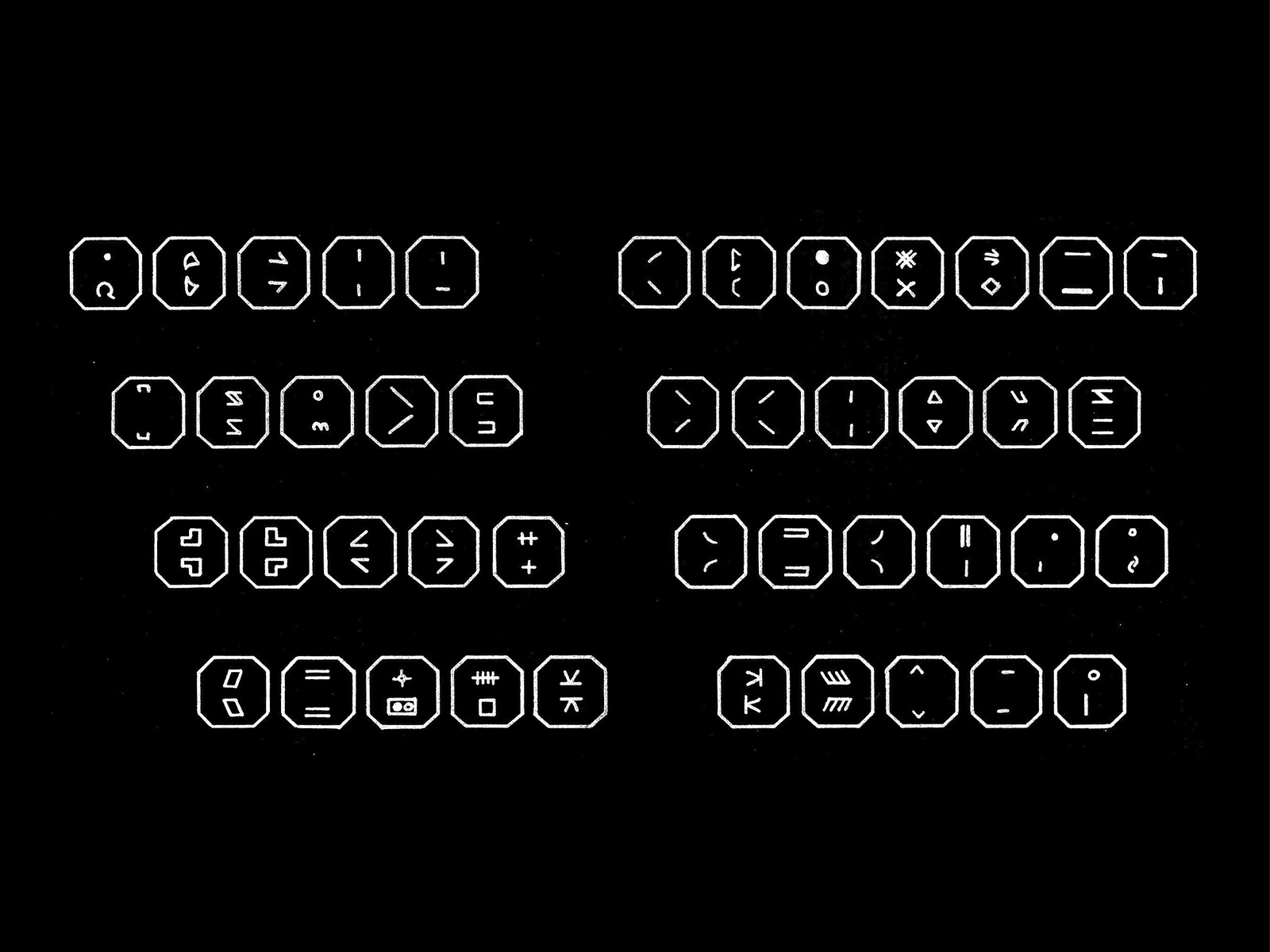

Expanded Labanotation keyboard arrangement from the Instruction Manual For Use With The Labanotation the IBM Selectric (1974)

In 1966, the Dance Notation Bureau collaborated with International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) to develop a new Labanotation typing element for IBM’s Selectric. The Selectric replaced typing arms with a golf-ball shaped typing element that prevented jams and allowed for font changes and customization. Its electric mechanism smoothed out the natural human variances in keystroke pressure, creating even darkness and thickness across letterforms for the first time. Typewritten dance notation documents, with their artful combinations of handwriting over delicate, machine-crafted symbols, are intriguing objects of beauty. They were produced from 1973 until around 1986, when computer graphics began to replace typewriting. Only a handful of typewritten scores—fascinating, beautiful documents––still exist.

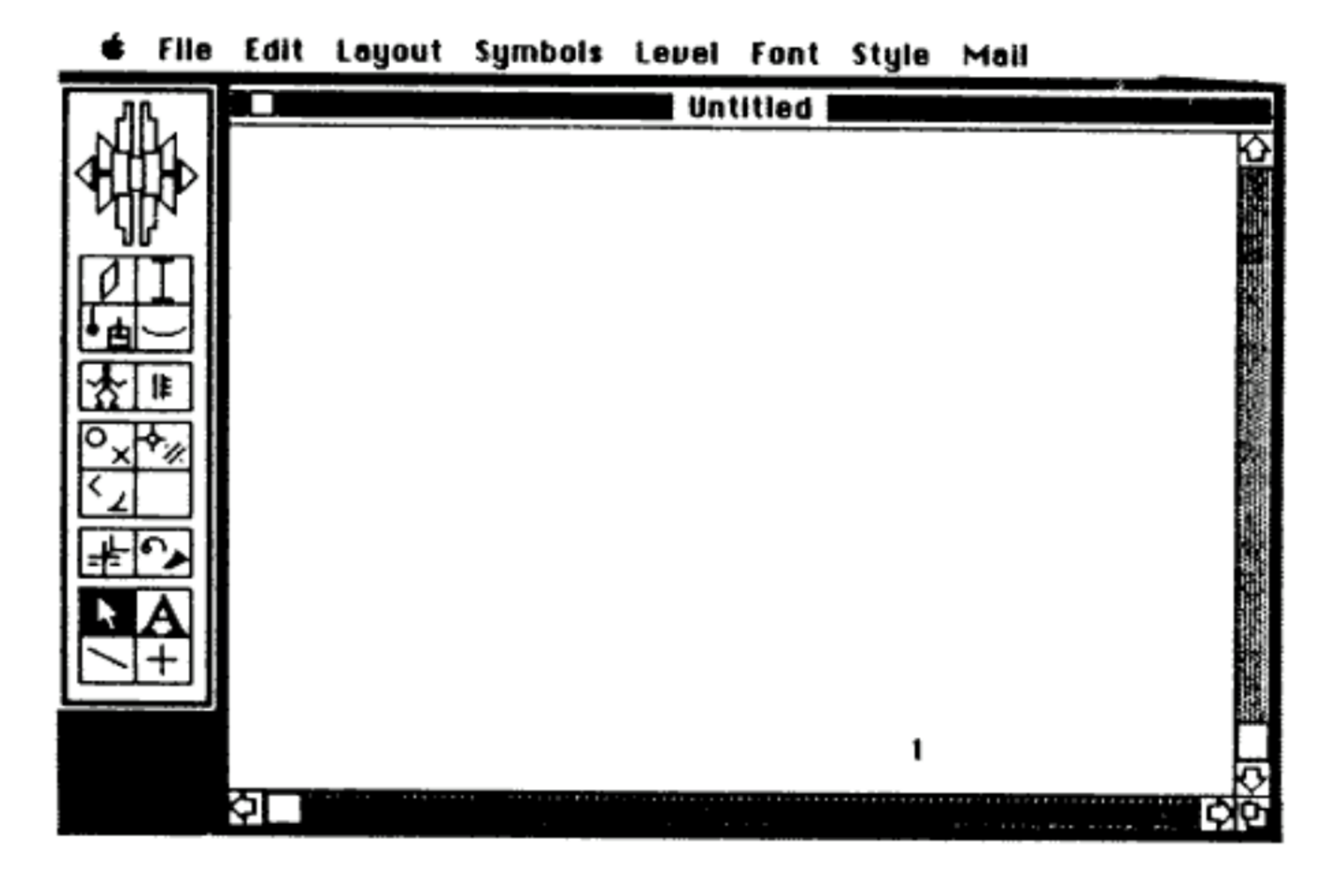

LabanWriter software (c. 1986)

Furthermore, by mediating movement information through a keyboard, the typing of movement notation paved the way for new forms of computing. Developers started considering the keyboard as a possible input for movement as data for computer applications.15Maxine D. Brown, Stephen W. Smoliar, and Lynne Weber, “Preparing Dance Notation Scores with a Computer – ScienceDirect,” Computers & Graphics 3 (1978): 1–7. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0097849378900183; Lynne Weber, “Using a Computer to Prepare Labanotation Scores,” Dance Research Annual IX (1978): 243. Throughout the 1980s, several notators worked on graphical user interfaces for dance notation. Lucy Venable, an expert notator, created LabanWriter. A trial version of this software made the dance typewriter obsolete in 1986.16Venable, “Archives of the Dance: Labanwriter”.

Merce Cunningham working with Elliot Caplan on Mr. Caplan’s documentary “CRWDSPCR” (1993)

There were other computing applications to describe and analyze, many of which passed their representations of movement through Laban concepts.17Judith A. Gray, Dance Technology: Current Applications and Future Trends, (Virginia: The American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 1989). LabanLens, the software for the HoloLens tool, created by Kosstrin and Summers, allows a dancer moving in the studio to digitally write notation in with gestures.18https://dance.osu.edu/labanlens Discussions have taken place about OCR for Labanotation, allowing machines to properly read notation texts. In this overall history, the typewriter played a large role in providing the bridge from handwritten production to computing with movement.

Dancers using the LabanLens augmented reality glasses

LabanLens interface demo

As document production and copying methods have evolved over time alongside emerging technologies, their aesthetic of uniformity has increasingly de-contextualized the document. With each technological development, including graphical software read on a screen, the ground upon which the document is written has become less visible. This phenomenon is in no way unique to dance notation. However, from where I sit, dance notation documents offer a unique opportunity to remember the materiality of graphics. At this moment, as generative AI offers the illusion of disembodied synthesis of information, reading and writing dance can bring back something that is so easy to forget: the materiality behind texts.