The Internet Exists on Planet Earth

The text that follows originally appears in the book Image RIP by Geoff Han, published by Source Type. Read more about the book here.

We’re in Tunisia talking about the internet. More than 2750 attendees from 700 organizations in 122 countries are at the RightsCon Summit1RightsCon, 2019, https://www.rightscon.org for five days to discuss digital rights, human rights in the internet era.Who do I mean by we?2Nabil Hassein, lecture, “Computing, Climate Change, and all of our Relationships, 2018, https://www.deconstructconf.com/2018/nabil-hassein-computing-climate-change-and-all-our-relationships At tech conferences I’ve attended in the past, we means technologists, engineers, and designers in the Global North. Of the eight RightsCon summits held so far, three have taken place in the Global South, with this as the first in the Middle East and North Africa, and the 2020 conference is slated for Costa Rica. Most attendees are policy makers, technologists, academics, government representatives, or journalists.

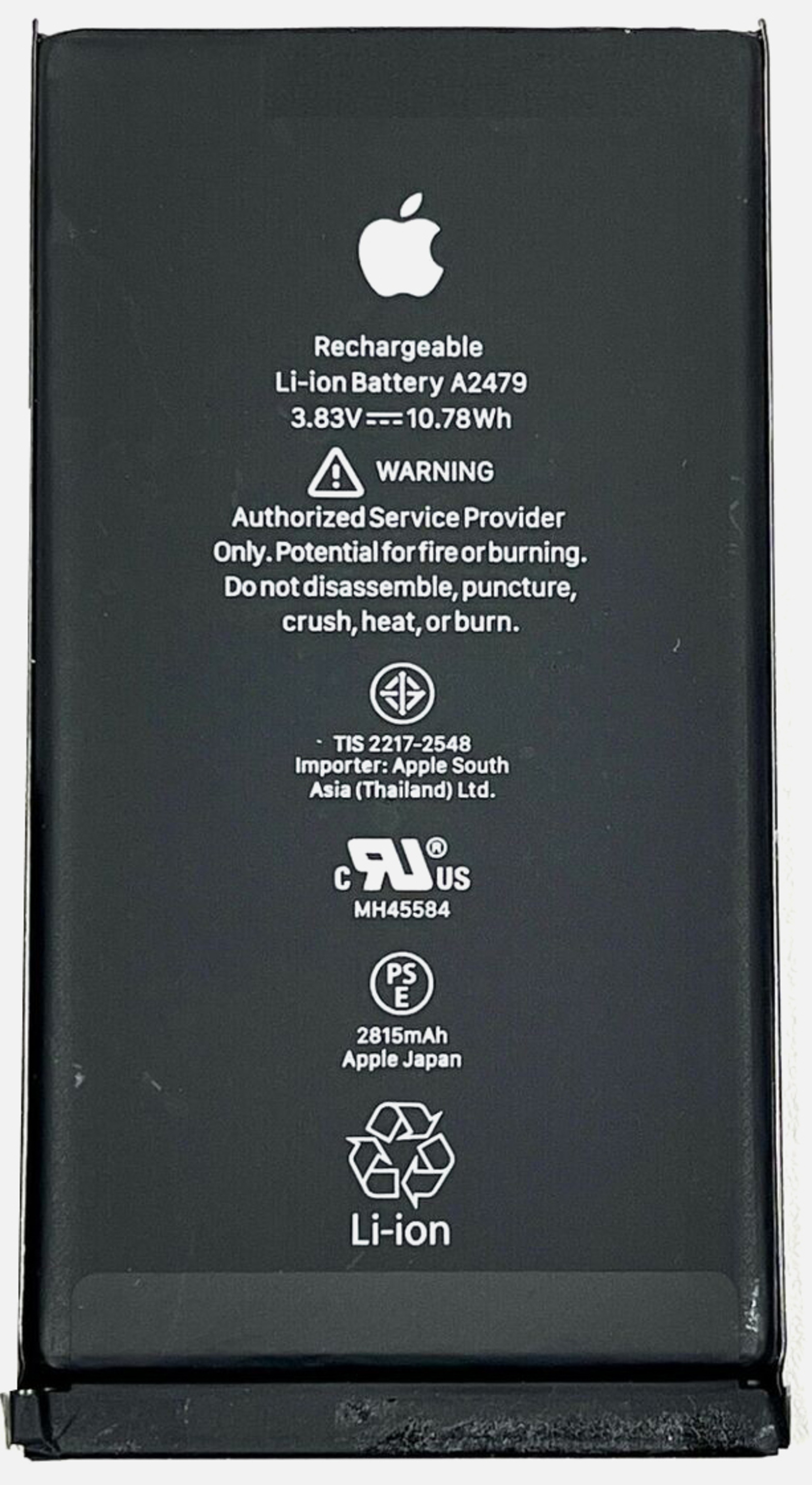

Attendees fly in from around the world, which means, in effect, that they pump out emissions to come speak about human rights. Despite this, the conference does not address the climate crisis in its programming or production. Of 450 events, hundreds surround cybersecurity, data stewardship, surveillance, public interest tech, artificial intelligence, political participation, content moderation, and more. Only a few touch on environmentalism at all. But digital technology is ultimately part of the ecosystem. Rare earth minerals are mined and embedded in cell phones by underpaid workers; factories require water and energy; data travels in fiber-optic cables on the ocean floor. What do we mean when we say digital rights?

In the 1960s, media theorist Marshall McLuhan foresaw the internet as a global village. “We have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace,” he wrote, “abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned.”3Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, 1964 If we’re all part of this integrated planetary nervous system, do we need to fly across the world to talk about it in close proximity?

A mine near Kolwezi where workers extract Cobalt, a material used in the rechargable batteries of phones and cars.

Gallium, a metal that melts in the palm of the hand, is used to fabricate various electronic compoents in cell phones.

Cobalt, known as “blue gold”, is a main ingredient in the fabrication of rechargable batteries.

Nickel is a key component of the microphone used in phones.

Indium is a metal used in the screens of phones allowing them to operate as a touch screen.

Magnesium is used in the casing of phones due to its ability to barricade the electromagnetic field of a device.

Water

In what’s called the Beehive (the glowing honeycomb ceiling is likely the source of its name), three lightning talks are slated to discuss environmentalism under the umbrella Land and Labor in a Digital World4RightsCon, “Lightning Talks: Land and labour in a digital world,” 2019, https://rightscon2019.sched.com/event/PwI9/lightning-talks-land-and-labour-in-a-digital-world#. There are perhaps ten people in an amphitheater suited for 300.

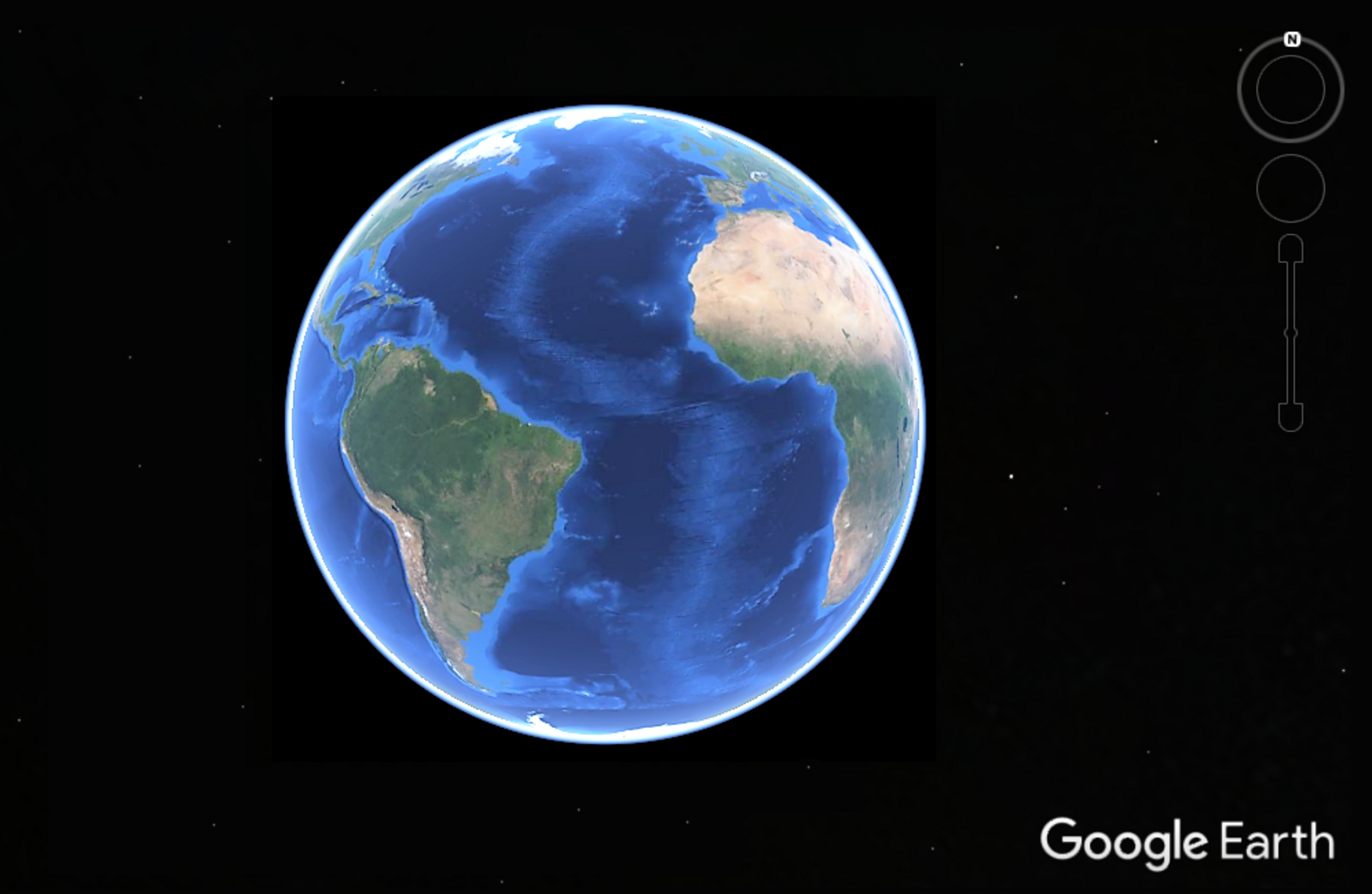

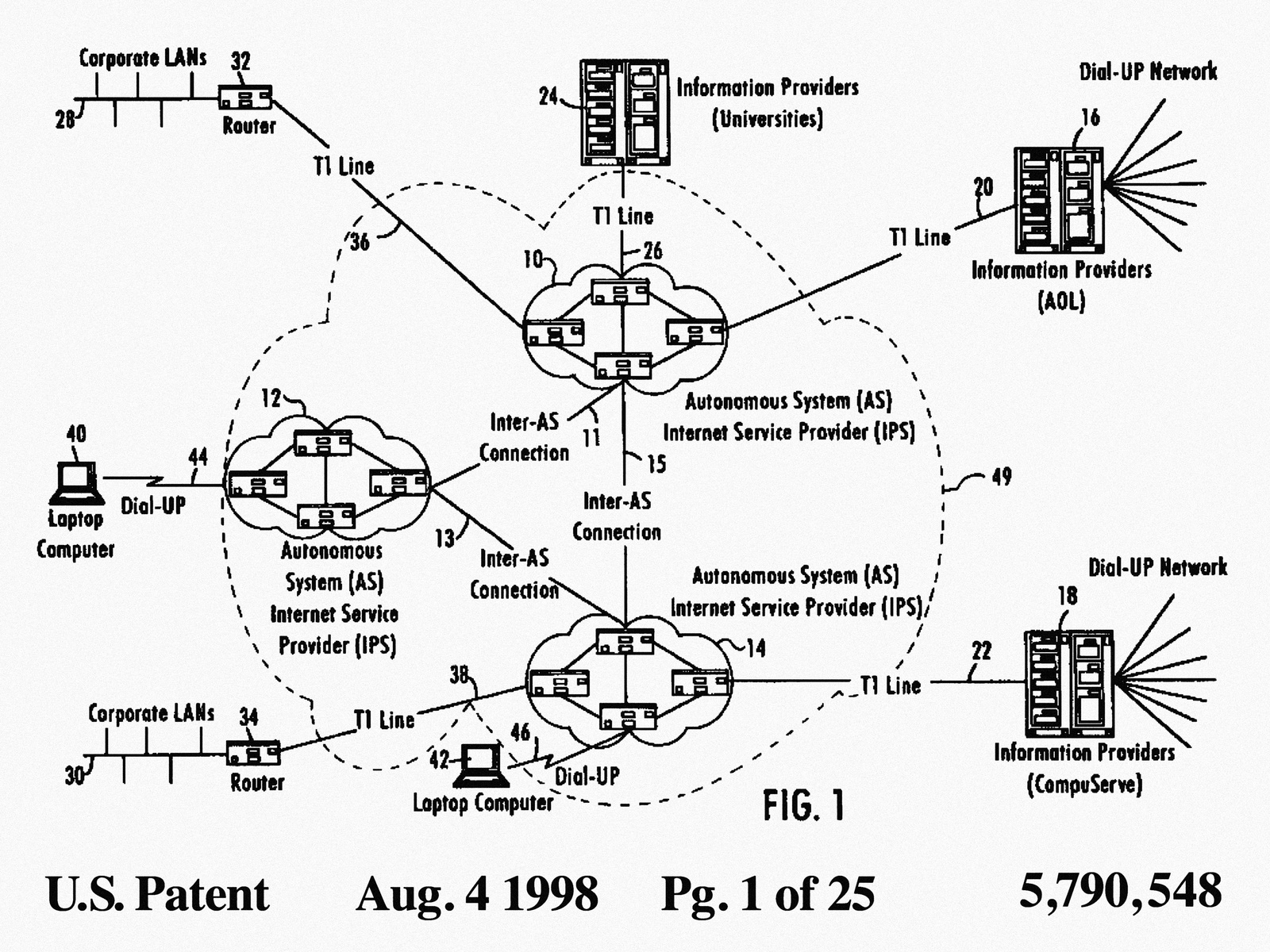

I’m here specifically for Matthew Battles’s Declaration5Declarations and manifestos are ubiquitous in internet activism, most notably the 1996 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” by John Perry Barlow, an early paper that interrogated governance on the emerging Internet. Barlow, founder of the cyberlibertarian Electronic Frontier Foundation, was also the inaugural fellow of the Berkman Klein Center for the Internet & Society, the organization that is also sponsoring Battles, Ricaurte, and me to attend this conference. (a) John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” 1996, https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence (b) “Cyberspace does not lie within your borders. Do not think that you can build it, as though it were a public construction project. You cannot. It is an act of nature and it grows itself through our collective actions.”of Digital Rights for the Natural World6Matthew Battles, lecture, “Declaration of Digital Rights for the Natural World”,” 2019 . He begins with NASA’s 1972 photograph of the earth from space, “Blue Marble,”7NASA, Blue Marble photograph, 1972 which “became the root of a global environmental consciousness.”8Erik Conway, Atmospheric Science at NASA, p.123, 2008, https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/71303/pdf Four decades later, the most visible image of the world appears as a collage of satellite photographs on Google Maps. Google’s servers and data centers—collectively, “the cloud”9“The cloud” was first used in 1996 in a Compaq document, formerly patented as the “universal access multimedia data network”.(a) “Cloud computing” was defined by Professor Ramnath Chellappa in 1997,(b) and became ubiquitous when Amazon Web Services launched Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) in 2006. (a) Antonio Regalado, MIT Technology Review, “Who Coined ‘Cloud Computing’?,” 2011, http://www.technologyreview.com/news/425970/who-coined-cloud-computing/(b)Ramnath Chellappa, Emory Goizueta Business School, https://goizueta.emory.edu/faculty/profiles/ramnath-k-chellappa—instantaneously generate the whole earth each time we access the site.

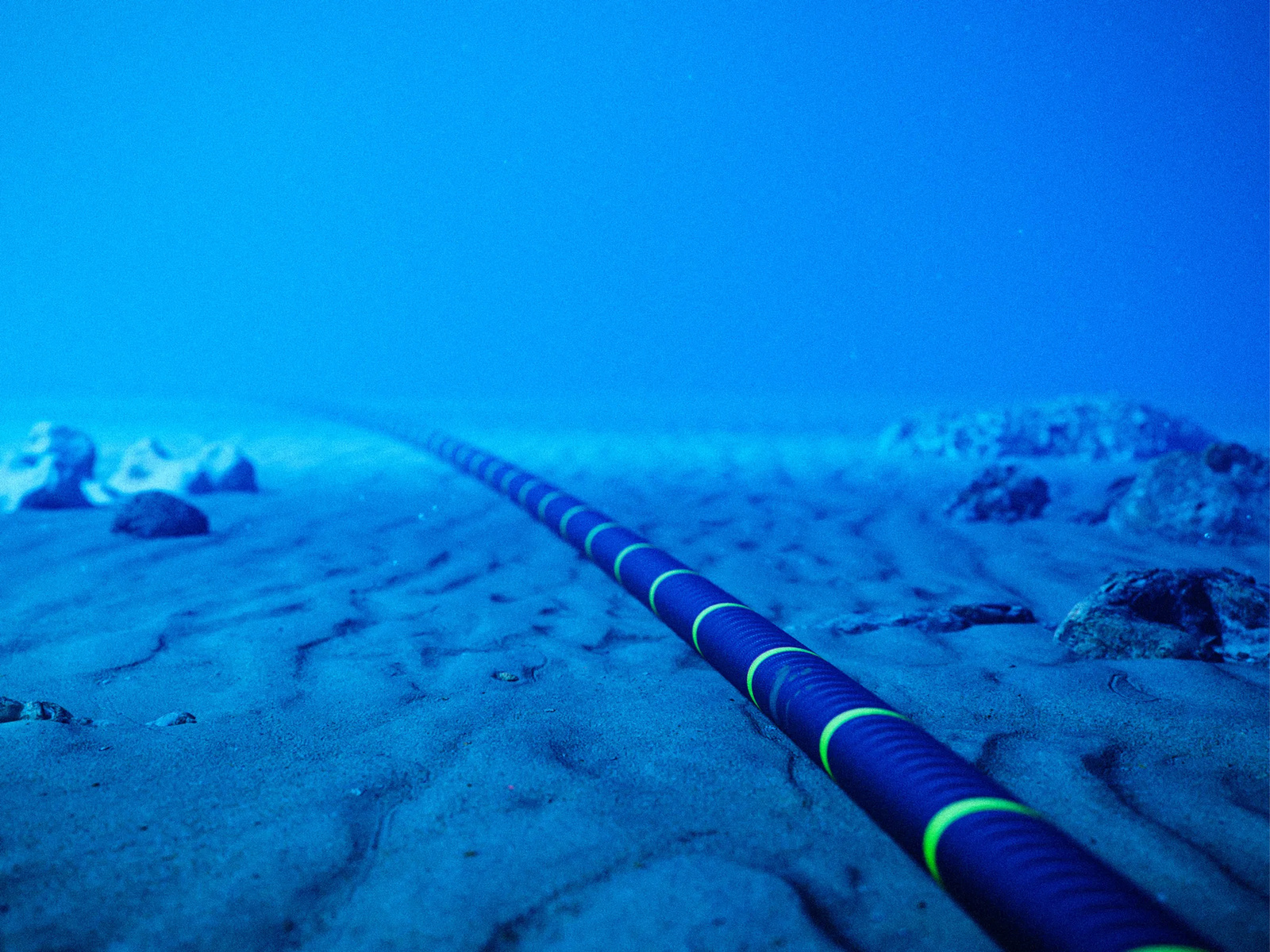

This name, the cloud, with its connotations of the ephemeral and intangible, is a misnomer. The data used to make the Google Maps image travels around the globe in fiber-optic cables sitting on the ocean floor. “People think that data is in the cloud, but it’s not,” said Jayne Stowell, who oversees construction of Google’s undersea cable projects, “It’s in the ocean.” Currently, Google is connecting the USA and Chile with a massive cable delivered on a 456-foot ship called Durable.10Adam Satariano, New York Times, “How the Internet Travels Across Oceans,” 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/03/10/technology/internet-cables-oceans.html

Image of the world via Google Earth created by a collage of satellite photography

Unlike meteorological clouds, which are largely composed of water, data centers of “the cloud” require the constant input of enormous amounts of water to exist. Directly, it’s used to cool the location, since servers release a lot of heat. Indirectly, it’s used to generate the electricity required to run the server farms.11Water Footprint Calculator, “Data Centers, Digital and Water Use,” 2018, https://www.watercalculator.org/water-use/data-centers-water-use/ Data centers in the USA alone are expected to use 174 billion gallons of water in 2020.12Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, “Data Centers and Servers,” https://www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/data-centers-and-servers

Blue Marble, NASA (1972)

A diagram from the patent for “the cloud” showing a dotted line in a cloud-like shape to indicate a network of computers and storage devices.

Speaking of electricity, the internet also wastes a lot of energy. Contemporary websites are bloated with videos and images. Server-side programming languages generate websites on the fly by querying a database. This means that every time someone visits a page, like Google Maps, it is generated on demand.13LOW←TECH MAGAZINE, “Why We Need a Speed Limit for the Internet,” 2015, https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2015/10/can-the-internet-run-on-renewable-energy.html Mobile devices also increase internet usage per capita. More processing power causes these devices to degrade faster, so they need to be replaced more often.14LOW←TECH MAGAZINE, “How to Build a Low-tech Website?”, 2018, https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2018/09/how-to-build-a-lowtech-website.html Sending 65 short emails has a comparable carbon output to driving a compact car one kilometer. Sending five emails with large attachments is similar to burning 120 grams of coal.15Joshua Melvin, “What’s the carbon footprint of an email?”, https://phys.org/news/2015-11-carbon-footprint-email.html As of now, the internet already uses three times more energy than all of the wind and solar power resources worldwide could provide.16LOW←TECH MAGAZINE, “Why We Need a Speed Limit for the Internet,” 2015, https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2015/10/can-the-internet-run-on-renewable-energy.html

The hope for the early internet was to make it as infinite and free as the open sea. Ingo Niermann describes this utopian vision: “Cyber-anarchists founded ‘pirate’ parties. Cyber-capitalists evaluated the ‘seasteading’ of offshore pirate villages. Cyber-subculture went ‘sea punk.’”17Ingo Nierman, Avery Shorts, “Liquid Privacy,” 2019, https://us17.campaign-archive.com/?u=0026e8adfb06086a83c6cd300&id=cbd4b2fd45 But today, the sea is filled with fiber-optic cables, squeaky dolphins,18The British Government Communications Headquarters’s top secret, leaked, social media data collection and analysis project is called Squeaky Dolphin. The American version of the GCHQ is the NSA, most famous for their invasive surveillance strategies. This actually provides a good example of the physical infrastructure of the Internet. The NSA claimed that they only look into email that pass outside of the United States, which might imply that all people sending online messages to others inside the US might be free from surveillance. But even if I am sending an email to someone one block away, this might pass through a server in Germany, entering the confines of NSA surveillance. (a)GCHQ, Squeaky Dolphin, 2012, http://spring2017.designforthe.net/content/6-library/29-squeaky-dolphin/squeakydolphin_gchq-nbc.pdf e-waste islands and underwater drones. To Google employees, it’s not the electronic superhighway,19Nam June Paik coined ‘electronic superhighway’ in 1974, https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/electronicsuperhighway/ as so fondly described in the 1990s, but the “cable highway.”20Adam Satariano, New York Times, “How the Internet Travels Across Oceans,” 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/03/10/technology/internet-cables-oceans.html This marks the change at the heart of the cloud mythology: until about a decade ago, it was telecommunications companies that laid most of the cables. Now the Big Four—Google, Amazon, Facebook,Microsoft—do it themselves. Where previously, companies pooled resources together to create a shared freeway, cables are now increasingly privatized.

Despite the optimism surrounding the emancipatory potential of technology, the internet’s history is steeped in resource extraction and the military-industrial complex. Its secondary subcultural history is one of frontiering and the back-to-land movement. When we talk about an infinite and free internet, who do we think we’re emancipating?

AAE-1 internet cable running along the ocean floor

Workers inside a ship that is laying undersea internet cables. To maintain the cables they are spooled around a massive pole, one employee walks the cable aroudn the pole while the others make sure it does not snag or knot. (Image via New York Times)

Land

In the workshop “Routes of Technology Production: Maps and narratives to build our collective future”21Paola Ricaurte, workshop, “Routes of Technology Production: Maps and narratives to build our collective future”, 2019, https://rightscon2019.sched.com/event/Pvr1/routes-of-technology-production-maps-and-narratives-to-build-our-collective-future technofeminist researcher Paola Ricaurte outlined the supply chain of technological production from design to disposal, and the close ties between technology, the body and territory.22Paola Ricaurte, “Data Epistemologies, The Coloniality of Power, and Resistance,” 2019, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1527476419831640

“No resources are natural,” writes Kelly Pendergrast.23Kelly Pendergrast, Real Life Mag, “The Next Big Cheap,” 2019, https://reallifemag.com/the-next-big-cheap/ Only through extraction by man does coal change from rock to fossil fuel. In “Anthropocene, Capitalocene & the Myth of Industrialization,” Jason W. Moore describes Modernity and its prioritization of machine development and resource extraction as above “(re)production in the web of life.” Out of capitalism arose a violent binary: Moderns and nature. The latter contained the environment, indigenous people and women. All were considered as gifts that could be extracted and exploited.24https://reallifemag.com/the-next-big-cheap/ Jason W. Moore, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene & the Myth of Industrialization,” 2013, https://jasonwmoore.wordpress.com/2013/07/04/anthropocene-capitalocene-the-myth-of-industrialization-ii/

Data extraction requires computing power, development of algorithms, and storage, which in turn require energy (fossil fuels), labor, and nature (extracted minerals and metals), all assembled to create a seemingly ephemeral entity with excessive amounts of power for the primary goal of profit.25Kelly Pendergrast, Real Life Mag, “The Next Big Cheap,” 2019, https://reallifemag.com/the-next-big-cheap/ Phrases like “data is the new oil”26The first use of “big data” appeared in 1997(a). By 2006, the phrase “data is the new oil” was coined by Clive Humby(b). (a) https://www.forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2013/05/09/a-very-short-history-of-big-data/#76eb1bed65a1 (b) https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/aug/23/tech-giants-data attempt to equate the lucrativeness of data with oil, but it can equally be seen as surfacing the exploitation inherent in extracting oil27Zero Cool inverts the phrase, arguing that “oil is the new data.”(a) Production of oil has never been higher.(b) Tech giants help oil companies produce even more through the public cloud, which allows servers to be rented rather than purchased. Chevron’s latest deal marks Microsoft as their primary cloud provider.(c)(a)https://logicmag.io/nature/oil-is-the-new-data/(b)https://transportgeography.org/?page_id=5944 (c) https://news.microsoft.com/transform/chevron-fuels-digital-transformation-with-new-microsoft-partnership/ and data.

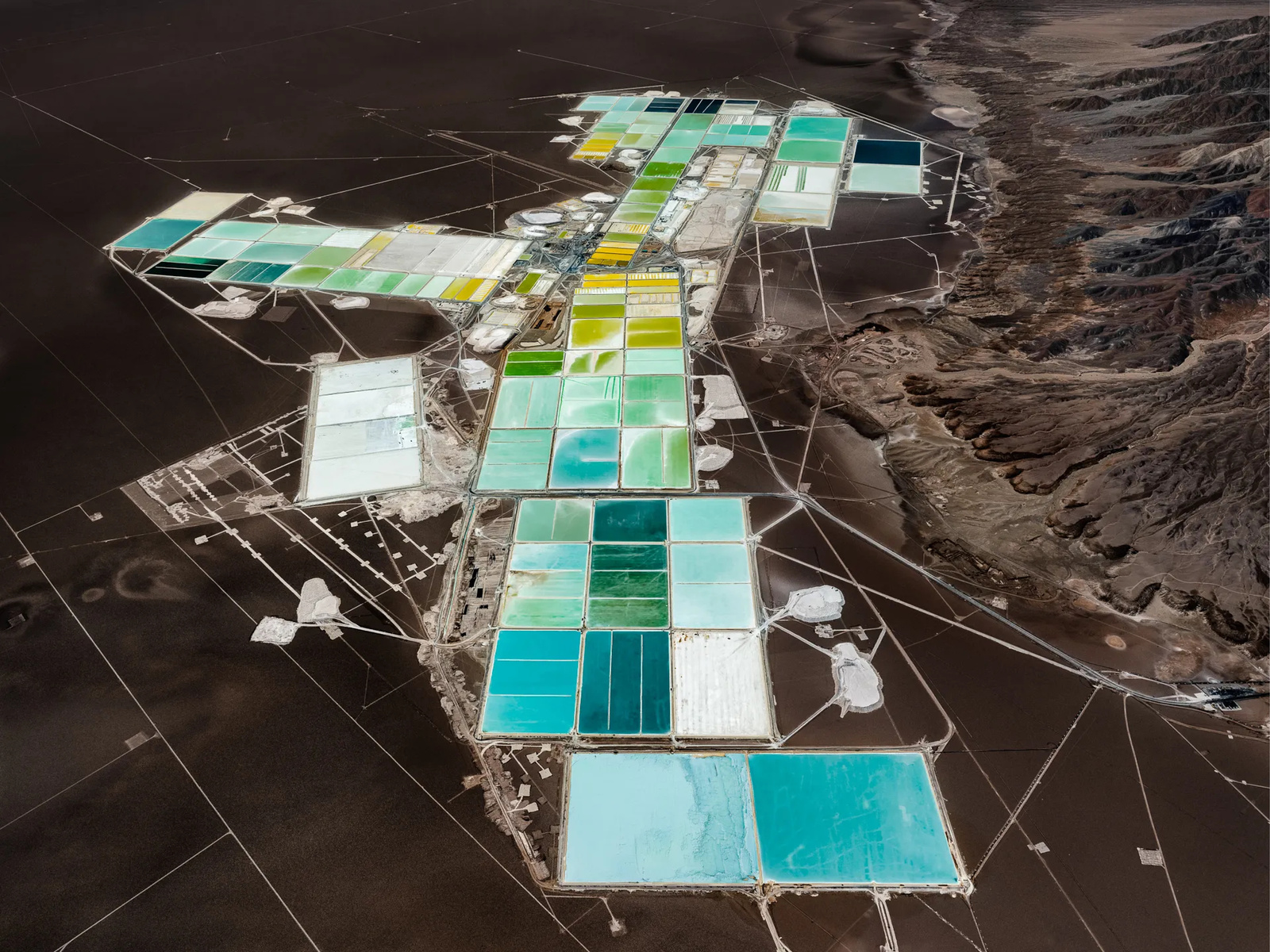

Lithium is a key component in the production of recharable batteries

The airplane I took from Boston to Tunisia most likely included the rare earth mineral niobium mined in Brazil, which produces 90% of the world’s niobium. Southwest of there, is the Salar de Atacama in northern Chile, the site of the world’s largest reserves of lithium, an essential rare earth mineral used in the batteries of our mobile devices. Latin America is one of the primary mining reserves in the world.28Inversíon Financias, “Latinoamérica apunta a la explotación de litio y niobio en una minería estancada en el pasado,” 2019, http://www.finanzas.com/noticias/economia/20190817/latinoamerica-apunta-explotacion-litio-4023035.html

Boa Vista Mine, Catalão, Goiás, Brazil

SQM Lithium Mine, Atacama, Chile

SQM Lithium Mine, Atacama, Chile

SQM Lithium Mine, Atacama, Chile

SQM Lithium Mine, Atacama, Chile

SQM Lithium Mine, Atacama, Chile

In Chile, an environmental court found that SQM29SQM, https://www.sqm.com/en/, the world’s second largest lithium producer, should be prosecuted over excessive water waste in the Atacama Desert, after complaints filed by indigenous communities close to its facilities. SQM and top competitor Albemarle both operate in the salt flats of this desert, the driest in the world, which supply more than one-third of the global supply of lithium needed for the batteries. The need for lithium has soared in the past several years and the country questions whether it can support this level of production due to the “particular fragility” of the Atacama ecosystem.30Aislinn Laing, Reuters, “Lithium miner SQM considering options after environmental court ruling,” 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-chile-sqm/lithium-miner-sqm-considering-options-after-environmental-court-ruling-idUSKBN1YV1JZ

In Brazil, an estimated 321 illegal mining points have expanded into Yanomami indigenous land. There are approximately 20,000 garimpeiros or “illegal minersm” six times more than there were only one year ago. Illegal mining has nearly destroyed the Sambingo River in Colombia, is a primary cause of deforestation of the Amazon in Peru, and is a root cause of the enslavement of thousands and sexual exploitation of many in mining camps.31Inversíon Financias, “Latinoamérica apunta a la explotación de litio y niobio en una minería estancada en el pasado,” 2019, http://www.finanzas.com/noticias/economia/20190817/latinoamerica-apunta-explotacion-litio-4023035.html

In Guadalajara, known as Mexico’s Silicon Valley, primarily women work on the production floor with the lowest salaries and an inability to climb the ladder. The labor union there, CETIEN, has called “for dignified and stable work,” demanding “that they stop harassing us and discriminate against us for being women,” and plainly, demanding “better conditions for women!”32Cetien, “La precariedad laboral en el Silicon Valley Mexicano,” 2018, https://cetienmexico.wordpress.com/2018/09/04/la-precariedad-laboral-en-el-silicon-valley-mexicano/

In China, a small province has become America’s electronic junkyard. With the high turnover of cellphones and other digital devices, e-waste is on the rise. A recent study by Basel Action Network33Basel Action Network, https://www.ban.org/ and MIT found that most of this ends up in Guiyu. They embedded 200 digital devices with GPS trackers and left them at various electronic take-back centers. Rather than recycling these, most are exported to rural provinces. The 2001 documentary Exporting Harm: The High-Tech Trashing of Asia 34Basel Action Network, “Exporting Harm: The High-Tech Trashing of Asia”, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDSWGV3jGek revealed the unsafe recycling practices. “Villagers desoldered circuit boards over coal-fired grills, burned plastic casings off wires to extract copper and mined gold by soaking computer chips in black pools of hydrochloric acid. Researchers later found the region had some of the highest levels of cancer-causing dioxins in the world due to its e-waste industry.”35Katie Campbell, Ken Christensen, PBS News Hour, “Where does America’s e-waste end up?”, 2016, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/america-e-waste-gps-tracker-tells-all-earthfix

E-waste landfill in Guiyu, China

In these examples, it’s already clear: the oft-heard utopic pronouncement “The internet is for everyone!” rings empty, as it will only end up supporting the goals of the makers and buyers while commodifying everyone else in the process. In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, Ursula K. Le Guin summarizes an afterthought by the poet Bill Siverly, “the essence of modern high technology is to consider the world as disposable: use it and throw it away.”36Ursula K. Le Guin, Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, “Deep in Admiration,” pM15

At the end of the workshop, Ricaurte speculates how to move forward: What are ways of creating technological tools specific to local communities rather than for the masses? How can we change the way we think about saving and sharing? Can we create technological biodiversity and embed permaculture, and whole systems thinking, into our daily uses?

“The internet exists on a living earth,” Battle reiterates, “Upon which it depends for its flourishing.” What would it mean to acknowledge that nature has a right to the goods of our technology? What would it be like to think of our own technology placed as a service to the planet that makes it possible? Based on the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights,37United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html Battles ends on a preamble of nine key points. The seventh calls for the recognition that our current era of digitality could not exist without “minerals and materials appropriated from earth, the very substrate of all life.” The eighth removes the distinction between the biosphere and the technosphere, both in the entangled network of earth and life. And finally, a proclamation of the Universal Declaration of Digital Rights for Nonhumans as a “common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations […] shall strive by teaching, design, and common action to promote respect for these rights and freedoms…”38Matthew Battles, lecture, “Declaration of Digital Rights for the Natural World”,” 2019

RightsCon 2020 will take place in Costa Rica and, this time, there will be a new track called Commitment to Sustainability. It seems the void I felt was noticed by many other attendees as well. When talking about digital rights in the time of climate crisis, it’s especially important to prioritize conversations about environmental justice, indigenous rights, sustainability and technology. In their open call, Access Now asks, “How do we collectively address the impact of technology on the environment? What is the best route for engaging and connecting human rights defenders from all focuses, including indigenous community organizers?”39RightsCon, “Thank you, Tunisia — hello, Costa Rica!” 2019, https://www.rightscon.org/thank-you-tunisia-hello-costa-rica-2/ It seems especially appropriate as Costa Rica announced its goal to be the first country to go 100% plastic- and carbon-free by 2021.40Rosamond Hutt, World Economic Forum, “Costa Rica wants to be the first country to ban all single-use plastics,” 2017, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/08/costa-rica-plastic-ban-2021/ Perhaps there, coming together again, we will discuss digital rights: sustainable development that is equitable and built on a foundation of respect for human rights.