Written into Existence

In 2016, the rapper Desiigner released the smash hit “Panda,” featuring a mumbled vocal performance which had fans everywhere attempting to translate the incomprehensible lyrics. In a shrewd marketing move, the lyric website Genius struck an exclusive deal with the rapper to get the correct words straight from the source. Things quickly soured, however, when the company realized their exact transcription appeared at the top of Google search at nearly the exact same time that the lyrics were published on Genius. The company had a hunch that Google was stealing their content, so they set up a trap: within a number of popular song lyrics, the company hid the word “REDHANDED” using a form of morse code with straight and curly apostrophes rather than dots and dashes. When the typographic pattern began showing up on Google’s lyrics, the company had what it needed for a lawsuit. While news outlets applauded Genius’ ingenuity, their scheme was actually a new take on an old trick called a copyright trap. By inserting inconspicuous or false bits of information into trademarked material, companies attempt to prevent plagiarism. If “trap” material is found in a competitor’s product, then it can be proven that infringement has occurred.

I. Lillian Mountweazel

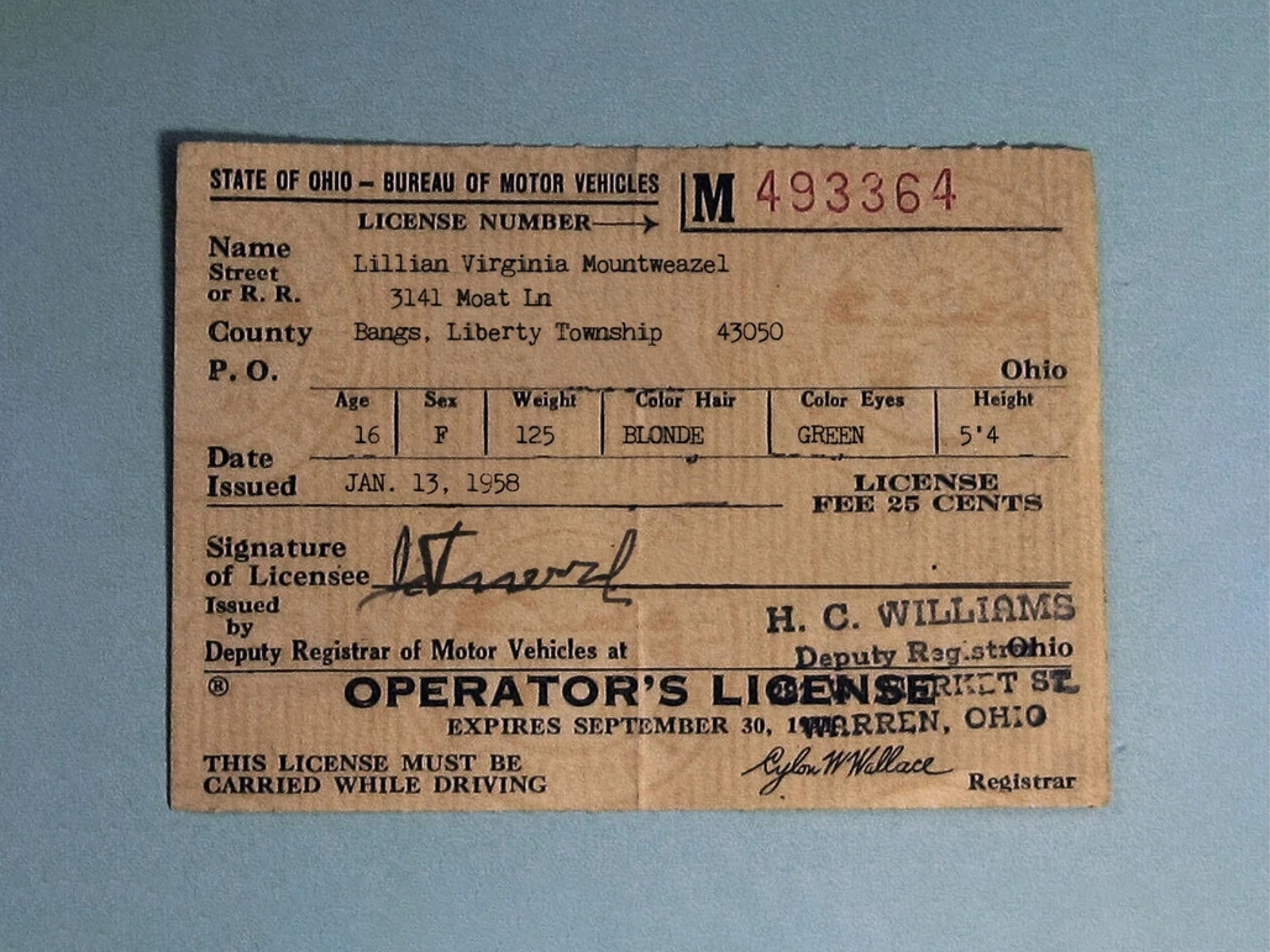

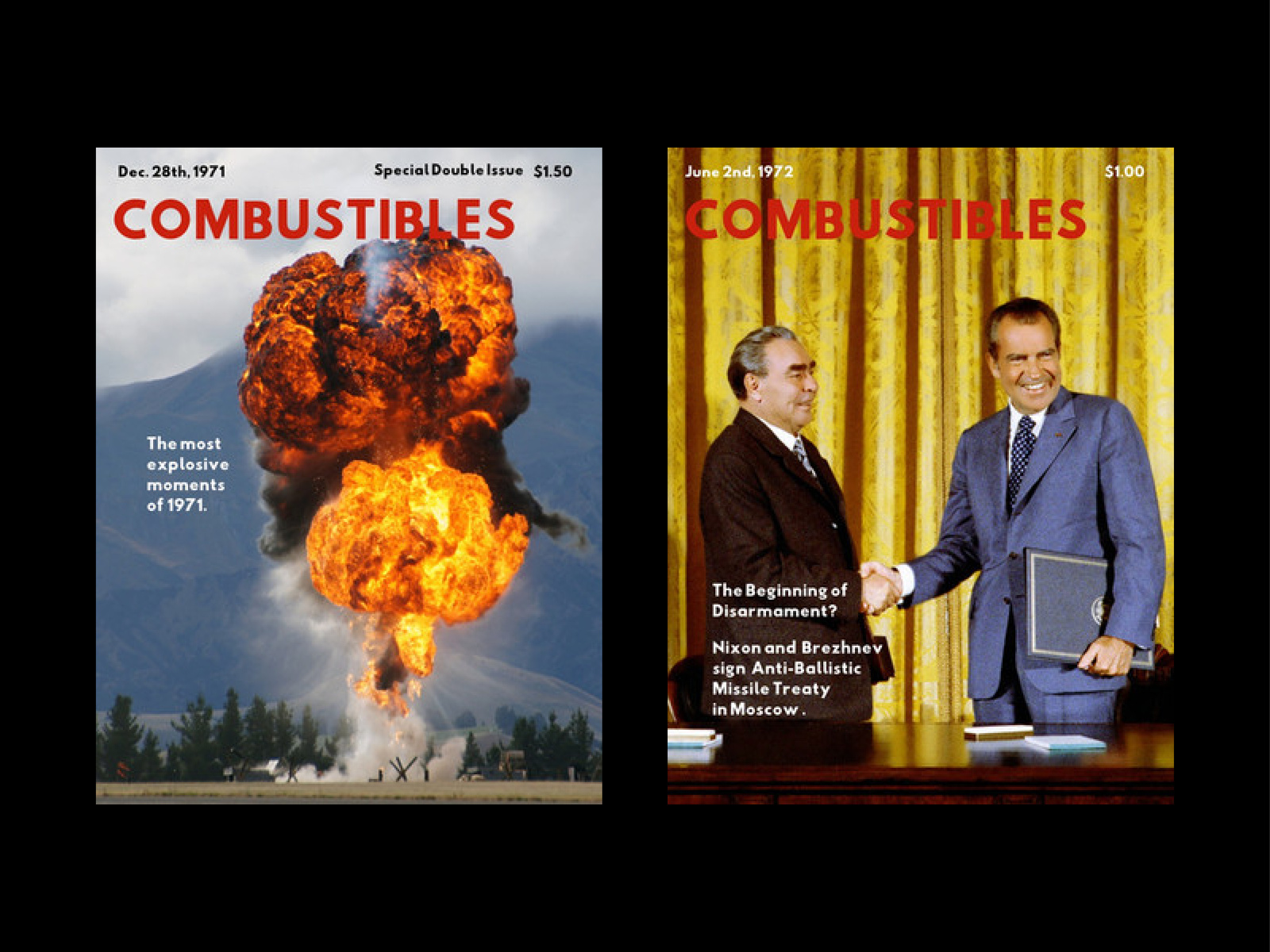

The aspiring designer Lillian Virginia Mountweazel was only 16 when she won a public design competition for a Korean War monument in downtown Beatosu, Ohio. The victory earned the young designer a series of commissions and her name quickly rose to prominence in the niche world of fountain design. But in 1963, for reasons unknown, the promising fountain designer gave up her practice to follow her new found passion in photography. In her images, Mountweazel focused on the more quotidian aspects of everyday life such as New York City buses or Paris cemeteries. In 1972, her photo series on rural American mailboxes toured extensively and was compiled into a best-selling book titled Flags Up!. At the peak of her photography career, while on assignment for Combustibles Magazine, Mountweazel was tragically killed documenting an explosion. Her death deeply affected the photography community, with several posthumous exhibitions of her work only further adding to her already rich legacy.

Image from Flags Up! series (1964–1970), Lillian Mountweazel

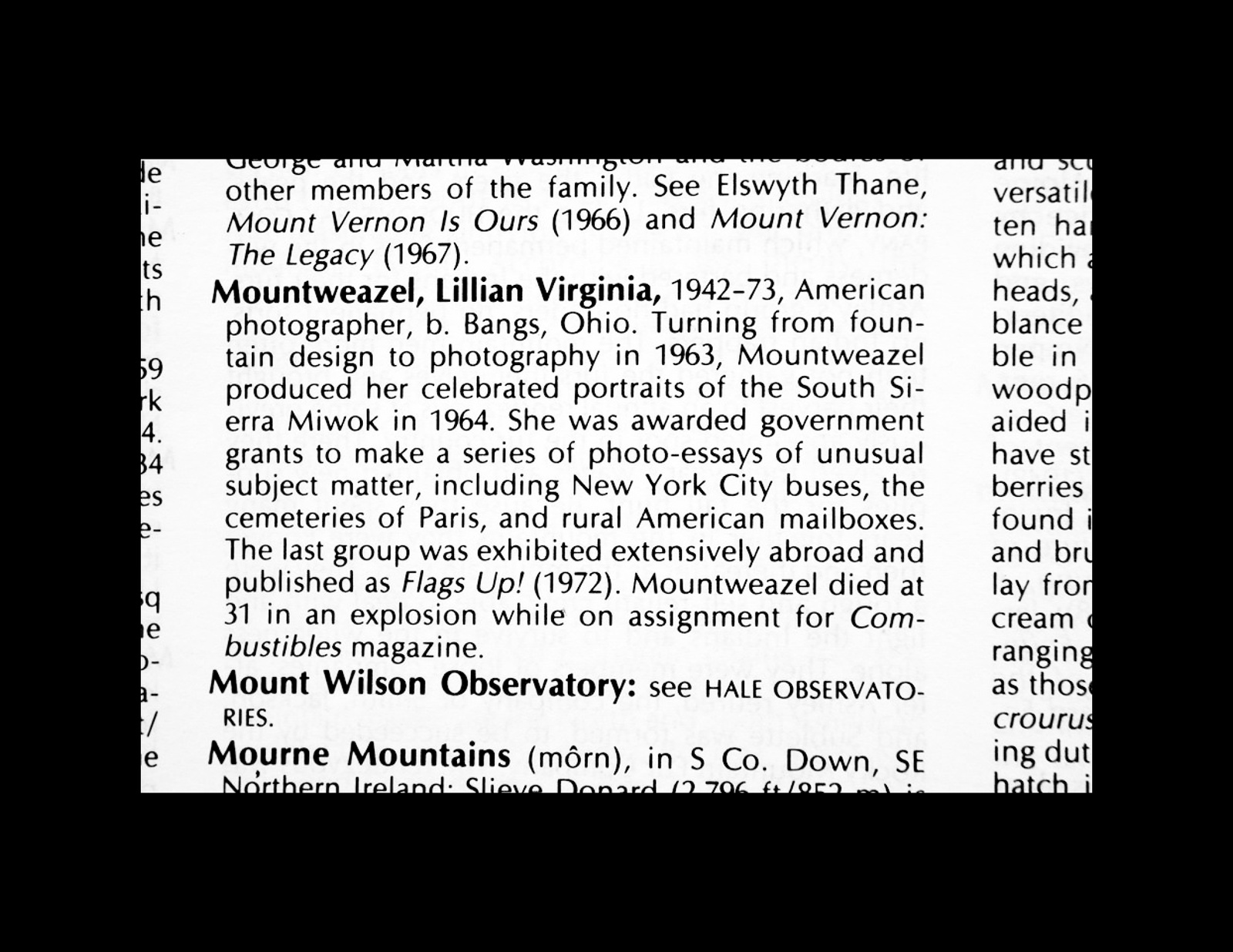

While Lillian Virginia Mountweazel is well remembered for her creative oeuvre, what is perhaps most striking about her story is that she never existed. Turn to page 1,850 of the 1975 edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia, however, and you will find an entry with her name, her life neatly summed up in three sentences. What’s an imaginary photographer doing in an encyclopedia?

“It was an old tradition in encyclopedias to put in a fake entry to protect your copyright,” recounts Richard Steins, one of the editors of that particular edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia. “If someone copied Lillian, then we’d know they’d stolen from us.”

And Mountweazel isn’t the only one. There is also Robert Dayton, a blind artist who pioneered the medium of “aroma art” (also in the 1975 edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia), and most recently in the 2005 New Oxford English Dictionary, the fake word “esquivelance” was implanted to catch content thieves. However, “Mountweazel” remains the most renowned thanks to a 2005 New Yorker article which turned the name into a neologism for the copyright trap technique. Following the article, fans of the fictional photographer started an online foundation with an active Instagram account dedicated to filling in the gaps of Mountweazel’s life, further blurring the boundary between reality and fantasy.

Lillian Virginia Mountweazel entry from the 4th Edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia (1975)

Lillian Mountweazel (1971)

Lillian Moutwezel’s drivers license (1958)

Korean War Veterans of Ohio Memorial, Lillian Mountweazel (1960)

Image from Flags Up! series (1964–1970), Lillian Mountweazel

Combustibles Magazine (1972)

II. Zzxjoanw

Prior to open source databases that aid many online information sources, compiling reference books such as encyclopedias, dictionaries, or maps took an immense amount of time, labor, and money (the 1934 edition of the Webster’s Dictionary took 558,000 hours to complete). Thus companies invested in such undertakings found it essential to protect their IP. But there was just one problem:these resources are understood as compilations of facts, therefore it can be hard to tell if a fact is copied or simply reported. On a map, for example, the location of any particular street should be the same… so if facts aren’t a reliable way to catch a forger, what about fictions?

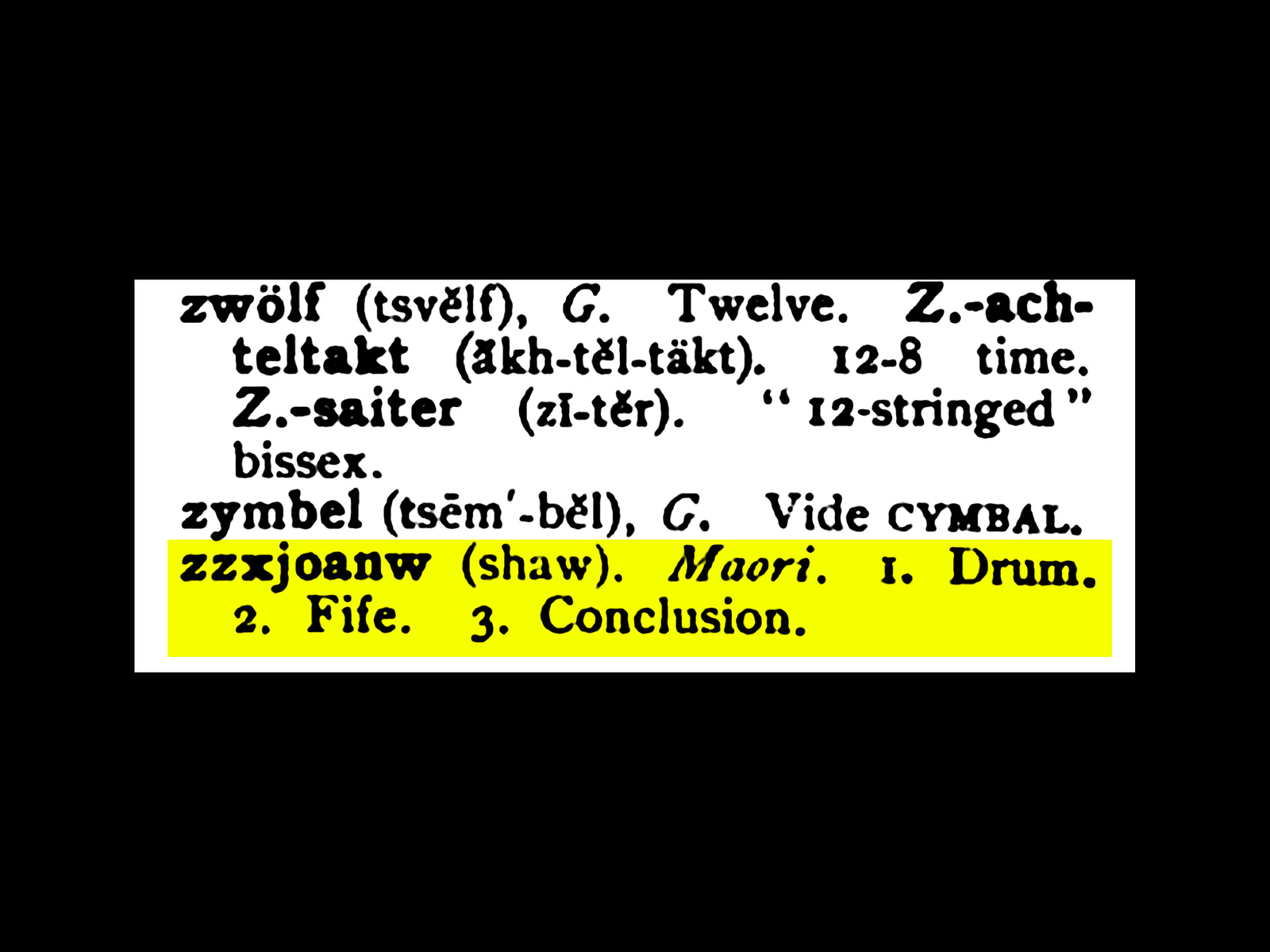

In my own research, the earliest known example of a copyright trap is the term “zzxjoanw” a Maori word defined as “drum,” “fife,” or “conclusion. The word first appeared as the last entry in Robert Hughs’ 1903 book The Musical Guide, an encyclopedia of classical music. While bearing a formal resemblance, “ghost words,” where a fictional term is left in the dictionary due to oversight—discussed amongst linguists almost a century earlier—should be understood as more of an accident than any sort of clever trap.

While copyright traps have historically been an effective way to catch a copycat, their strength in court has proven to be much more dubious.

Entry for “zzkjoanw” from The Musical Guide by Robert Hughs (1903)

III. Agloe, NY

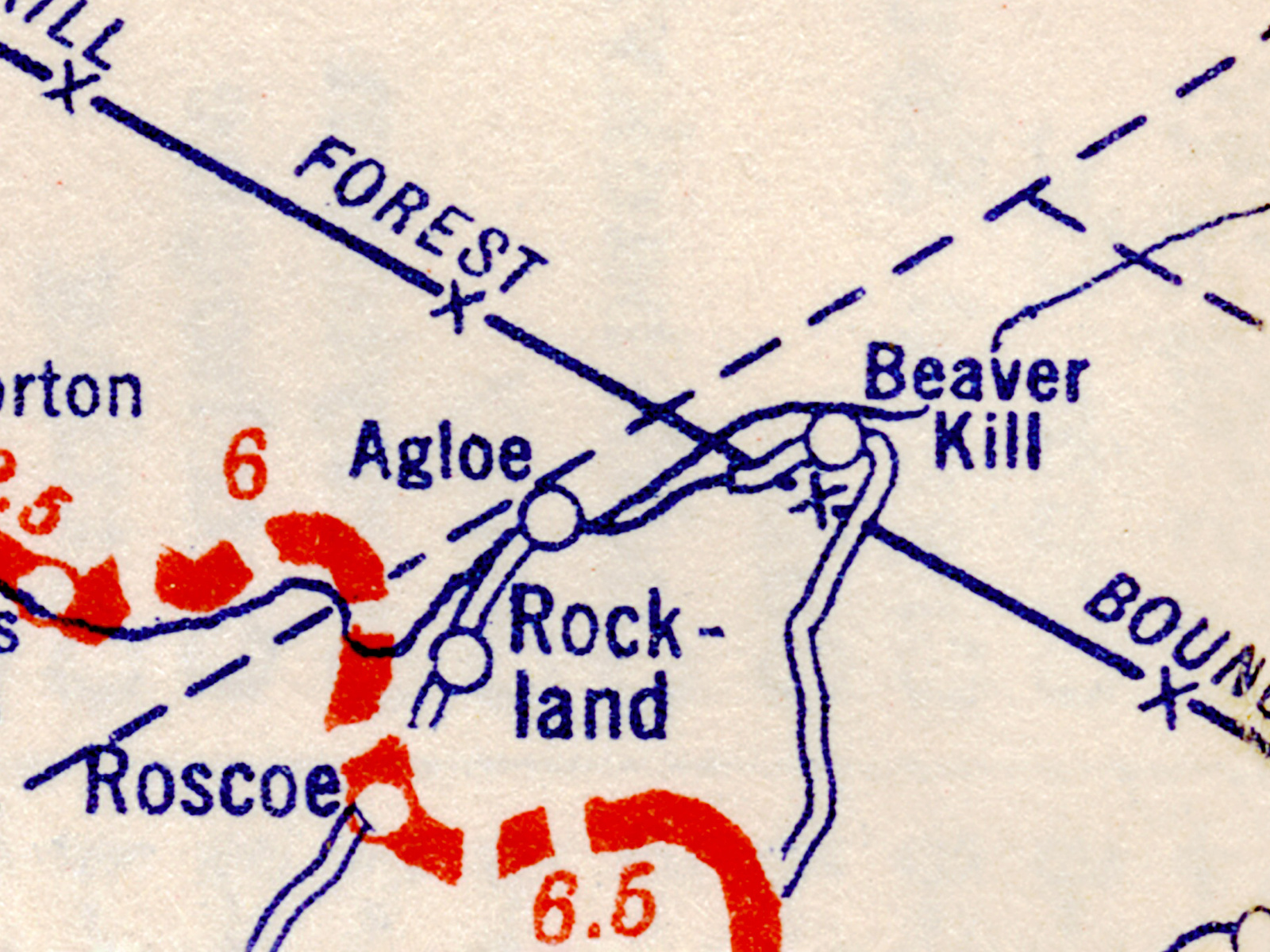

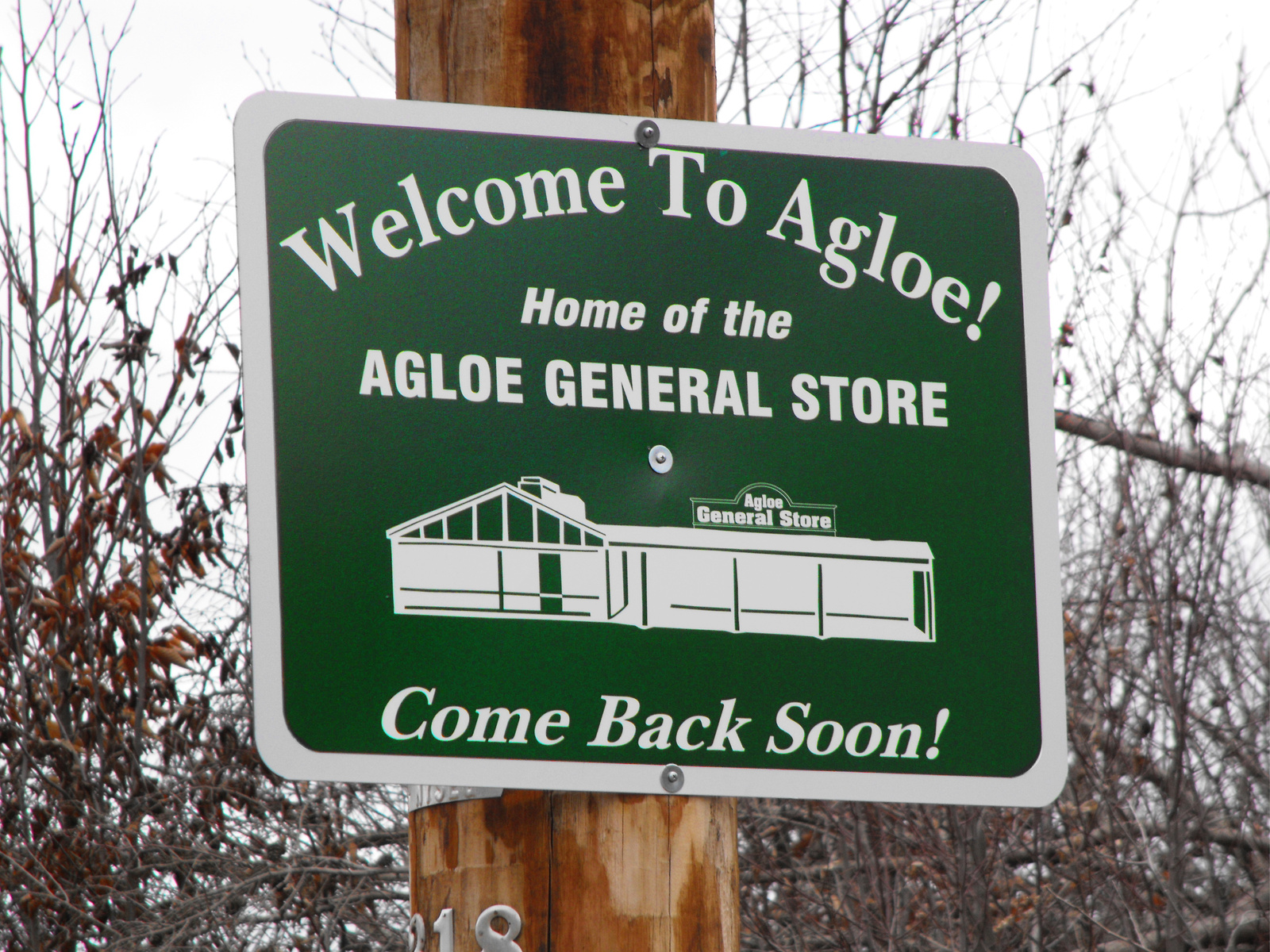

In the 1930s the General Drafting Co., seeking a way to prevent competitors from copying their maps, drew in a fake town called “Agloe” created out of the initials of the company’s director Otto G. Lindberg and his assistant Ernest Alpers. Like Mountweazel, if a rival company included the town on the map then General Drafting Co. would know it was a copy. The plan seemed iron clad until travelers in the area decided to open up a general store there. When looking for a name for their shop, they turned to the map and found their new business venture to be smack in the middle of Agloe. From that point on, Agloe General Store was open for business. A few years later, Rand McNally began distributing maps including the town of Agloe. When General Drafting Co. found out, they prepared to take McNally to court for theft of their IP. What seemed like a surefire victory was anything but. In court McNally, referring to the Agloe General Store stated that if the town was made up then how would such a business exist? The court ruled in favor of McNally, making General Drafting Co.’s fake town a reality. Years passed and Agloe General Store eventually closed. Yet Agloe still appeared on Google Maps until one day in March of 2014, it didn’t.

From fantasy to reality, and now forever stuck in a space of liminality, is Agloe real? As Elaine Fettig, the former president of the Roscoe-Rockland Chamber of Commerce, put it in a 2014 New York Times article on Agloe,“What’s your definition of real? If it exists in enough minds, it’s real.”

Like Mountweazel, Agloe isn’t a singular example, but it is the most well-known of the “paper towns” or “phantom settlement” phenomenon. There is Goblu and Beatosu in Ohio, which were created as an inside joke from a diehard Michigan University fan (“Go Blue” is the chant of the school, and OSU is their arch rival). Or Argleton, a “town” located somewhere in West Lancaster that received a significant amount of media attention after a blog from a neighboring resident went viral. The resident, who had grown up in the area and never heard of Argleton went to explore it only to end up in the middle of a field. Amidst my own digital explorations of these imaginary places I began to wonder, if a fake place can be mistaken for real, then is the inverse possible? Can borders be erased as quickly as they can be drawn?

The town of Agloe, NY, appearing on a map by the General Drafting Co. (1925)

Town welcome sign, Agloe, NY

The fictional Agloe General Store, long after closing…

An empty field that sits in the supposed location of Argleton

IV. The Bielefeld Conspiracy

The Bielefeld Conspiracy Theory began in an internet forum called de.talk.bizarre in 1994. It promoted the idea that Bielefeld, Germany’s 20th largest city, did not actually exist. The myth began when someone at a party said they were from Bielefeld to which another guest sarcastically replied “that simply cannot be” and the seemingly minor incident was reported online as a joke. Included with the message were three questions:

1. Had anyone actually met anyone from Bielefeld?

2. Have you ever been to Bielefeld?

3. Have you ever met anyone who has been to Bielefeld?

Like all great conspiracy theories, anyone who answered yes to any of these was said to have been duped or mistaken. The online myth reached peak publicity when in 2012 Angela Merkel recounted a meeting she had traveled to in Bielefeld, stating in her public remarks that it did seem to exist. In 2019 the town of Bielefeld was fed up and launched a marketing campaign offering up 1 million euros for any definitive proof that they did not exist. Following the competition (surprise, Bielefeld held onto their money) the town erected a giant boulder monument commemorating the decade-long rumor and celebrating the fact that they were, in fact, real.

A cartographer at the Federal Office of Topography in Switzerland. Image courtesy New York Times.

If you think hard enough about these scenarios it becomes easy to slip into philosophical cliche.What does it means to exist? Who creates reality? It might seem like we’ve gone too far down the rabbit hole. But these reference books— encyclopedias, maps, or dictionaries—in many ways do establish reality. And at times it’s easy to forget that these texts were written by human hand, prone to error, exaggeration, or commercial interest, rather than inspired by some divine truth. “It’s a little bit like being a god,” says Jurg Gilgen a specialized Swiss cartographer, “You’re creating a world.” And at times these worldbuilders are forced to make decisions based off of instinct and imagination. Thus distortions, liberties, and elaborations that may not exist are drawn onto the page and into existence.

The managaging director of Bielefeld Marketing and the creator of the Bielefeld Conspiracy present the Bielfeld Conspiracy Monument to the town (2019)

Desiigner, rapper of the hit single “Panda” (2016)

Copyright Traps RIP

If the Genius case at the beginning of this article proves anything, it’s that copyright traps no longer carry the same weight as they once had in the pre-internet world of publishing. Genius lost in their case against Google due to technicalities of who actually owns the copyright to lyrics and how strongly a company’s site policies hold up in a court of law. But more broadly, it speaks to the way information and knowledge today is compiled, checked, circulated, and copyrighted. Our most relevant source of information is not from any single author, but Wikipedia, run by 90,000 users who share the responsibility of creating, editing, and regulating information. What makes things even more difficult is that facts themselves feel more precarious than ever before. Elections are stolen, microchips are implanted via vaccines, and global decisions are being made by anonymous users on internet message boards. Today we mourn not only the death of Lillian Mountweazel, but the demise of the copyright trap itself. As we attempt our best to distinguish fact from fiction we remember the words of the artist Robert Dayton* who said: “…the best lies always bring us one step closer to the truth.”