Start Small to Touch the Wider

What can Shocking Pink, a feminist underground zine from the 1980s teach us about the future of publishing? Over 16 issues, the publication remained a shock to the mainstream offering blunt takes on issues ranging from sexuality to global politics all through their aggressive cut-and-paste aesthetic. Through a detailed look at their archives, first-hand conversations with members of the collective, and her own astute observations, author Michela Zoppi guides readers through the ways that publishing, design, production, and distribution can become potent tools in forming community and attacking unjust systems.

A good question from a good friend: How small do we start when it comes to talking about feminism? Should feminism be localized, scale down into discrete but powerful inner-movements? Do we talk about the first wave, the second, the third? Is it possible to draw a holistic picture of “the feminist movement” through close shots of its innerworkings, conducted at a scale of minor but material change, or through listening to the less public voices and paying attention to informal communication channels? How does scale, locality, and size affect feminist groups and the development of queer thinking?

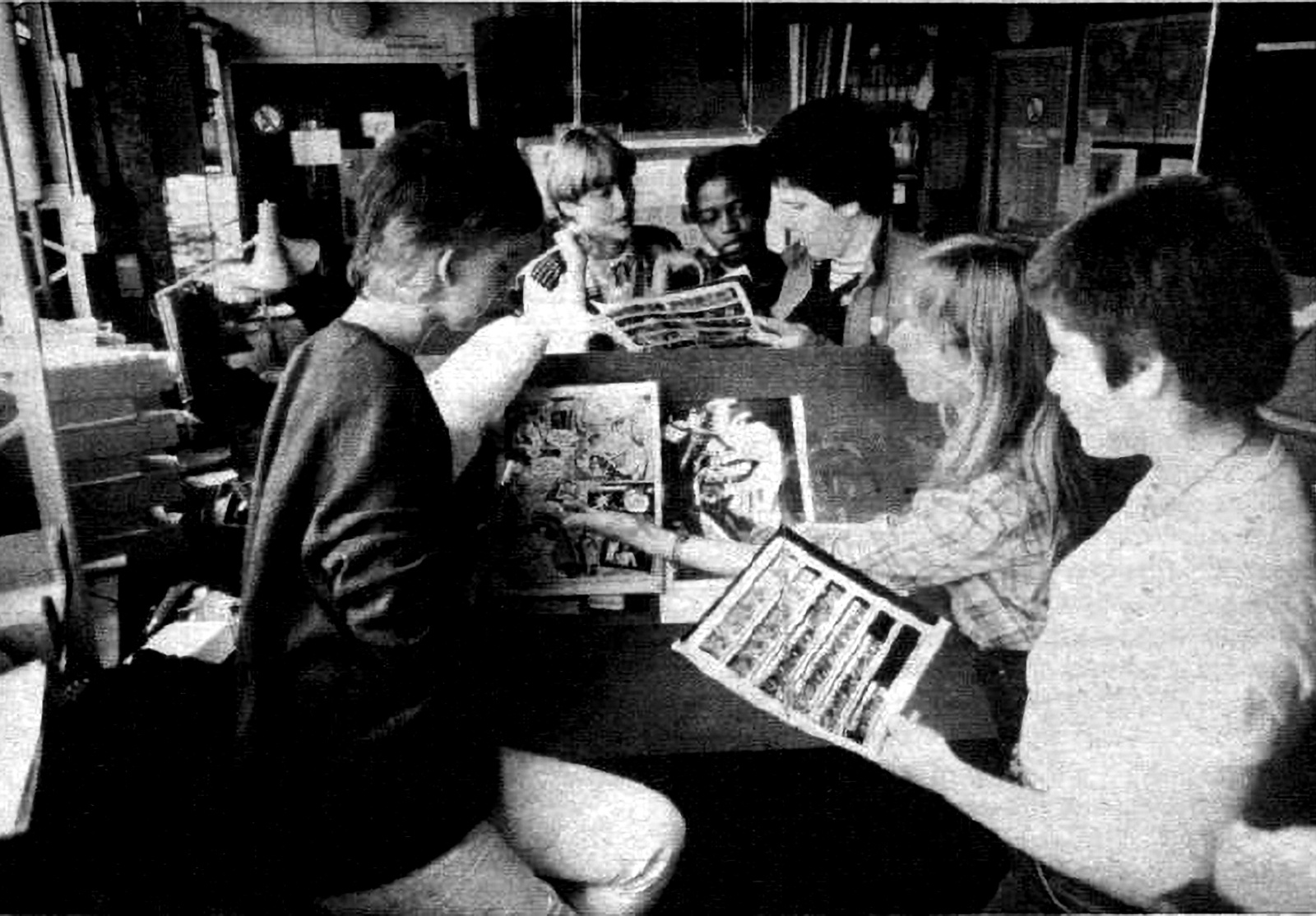

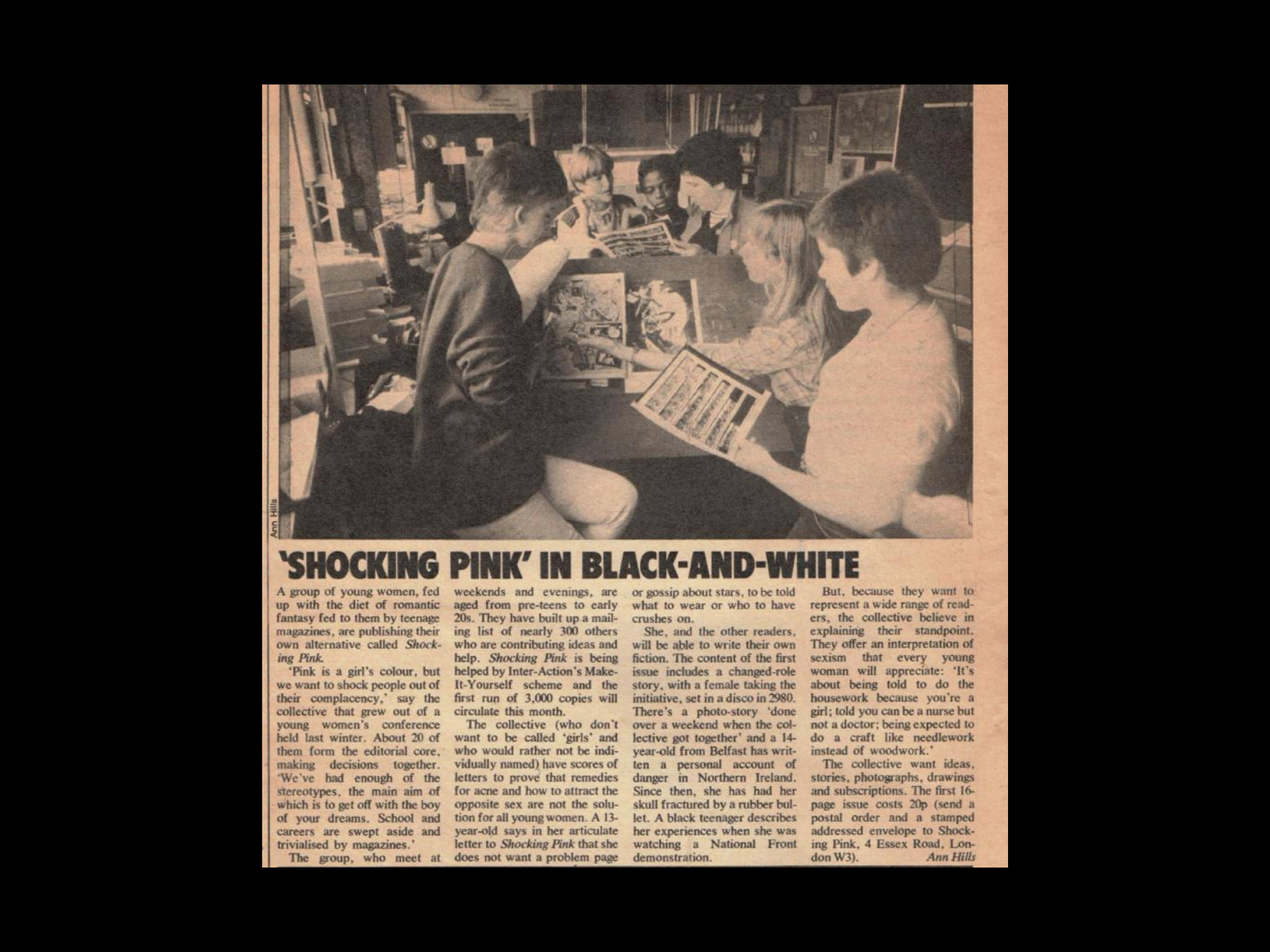

We might want to start small by talking about the “small” age of the founders of the London-based countercultural feminist magazine Shocking Pink(SP). In 1979, around 10 girls and young women between the ages of 12 and 22 gathered around an editorial table, feeling unrepresented as young women within the feminist movement. A small team, they embarked on a large project that spanned a decade of rapid social change, and became an important part of young women-led, feminist and queer activity in the UK. SP’s avant garde approach helps to better understand how the social movements of the ’80s and ’90s opened the way to our contemporary definitions of womanhood.

Though just one node in the sprawling network of feminist publishing, SP remains important to the conversations around femininity and feminism, particularly ones about the body, critical questions around white feminism, and societal and class struggles more broadly. SP successfully interpreted and presented “intersectional identities of race, class, and sexuality,” and although it arrives to us now as an historical document archived in libraries, the collective’s project at the time of its making was urgent and grassroot, and the knowledge SP passed on and the stories it told are still very much relevant today.

The first Shocking Pink collective (1980)

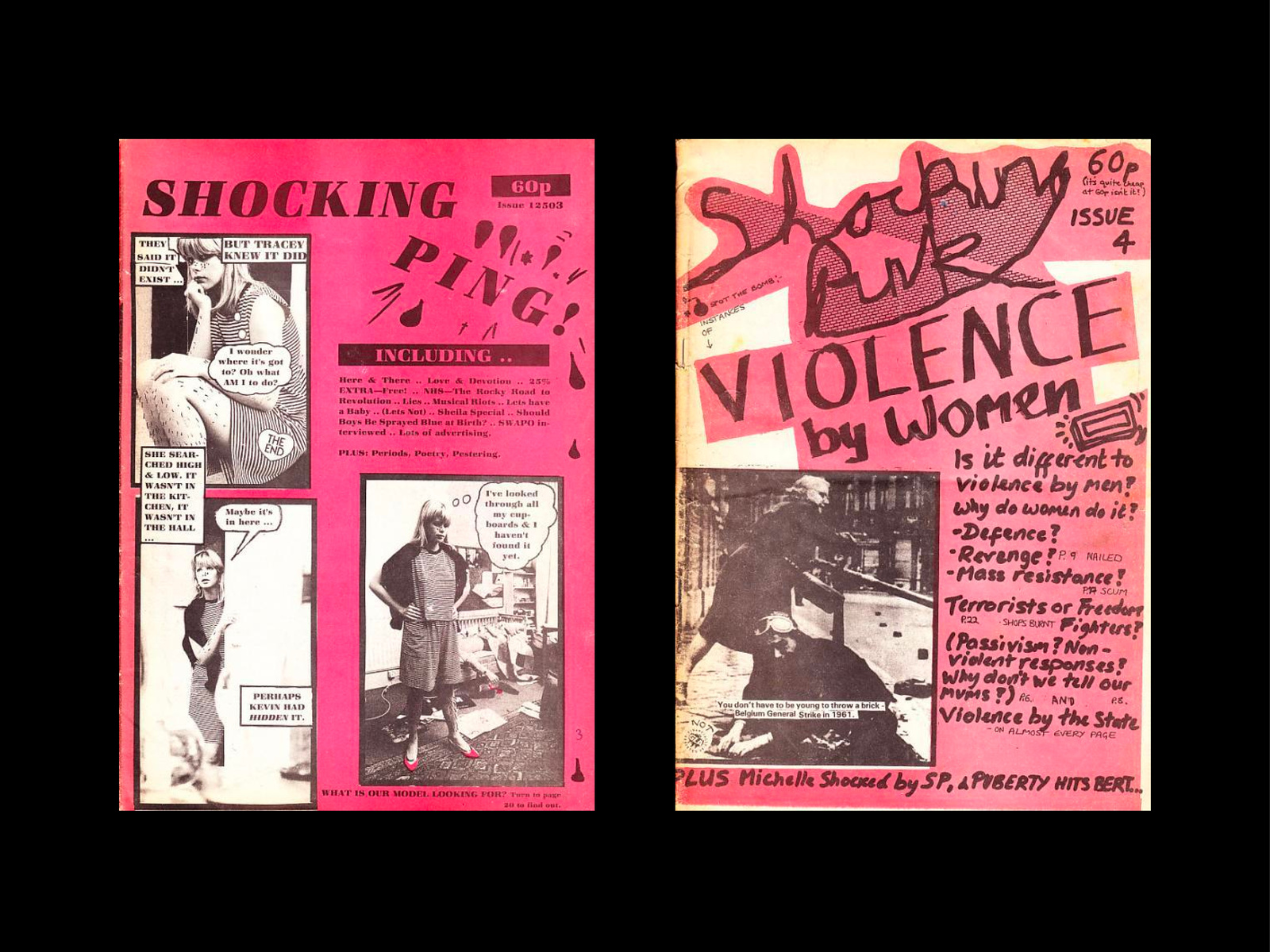

Shocking Pink covers, Issues 1 & 2

Shocking Pink covers, Issues 3 & 4

Shocking Pink covers, Issues 5 & 6

Shocking Pink covers, Issues 7 & 8

Shocking Pink covers, Issues 8 & 9

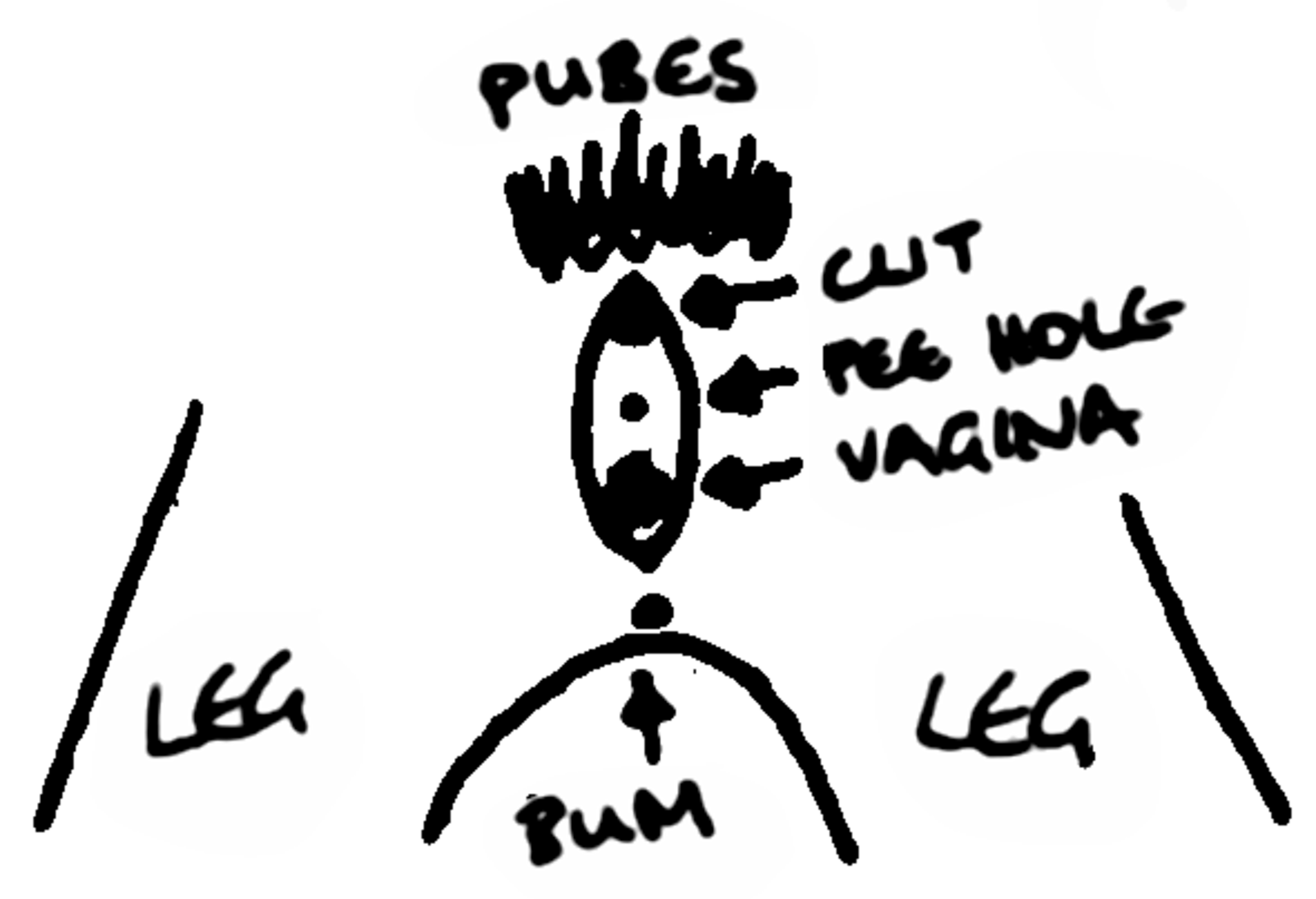

In the UK in the 1980s, anyone printing a magazine about sexuality, equality, abortion, gender, and race could be faced with prosecution. Nevertheless, Shocking Pink’s first editorial team — there was a succession of three teams over the years — decided to start their editorial adventure by publishing an article about masturbation in their second issue. The members of the magazine had the adamant feeling that, besides being a dangerous action, it was also a statement of complete freedom from the contemporary feminist editorial landscape. Since most diagrams of female anatomy at the time were rough, imprecise, vague, and didn’t include the clitoris, the editors chose to illustrate the article with the truest image possible: a photograph of a vagina, taken by Sally O-J, a 17-year-old founding member of SP. Their aim wasn’t radicalism; they ran the image to encourage readers to accept their bodies and be open about their sexuality. The issue was, of course, banned from libraries and many cultural places.

O-J found out about SP through The London Women’s Liberation Newsletter, when in 1979 it ran an ad calling for young people to attend a meeting for a new feminist magazine. The event took place at the Women’s Arts Alliance and was organized by Susan Hemmings, a member of the iconic UK feminist magazine Spare Rib. Hemming’s teenage daughter Lisa had expressed interest in making a magazine for her age group, something similar to Spare Rib but less serious in tone and geared toward the newer generation. The call was responded to by many; the group whittled down to the core collective in short order. During the second or third meeting, a member named Paula suggested that Hemmings didn’t need to run the meetings anymore — they would take it from there.

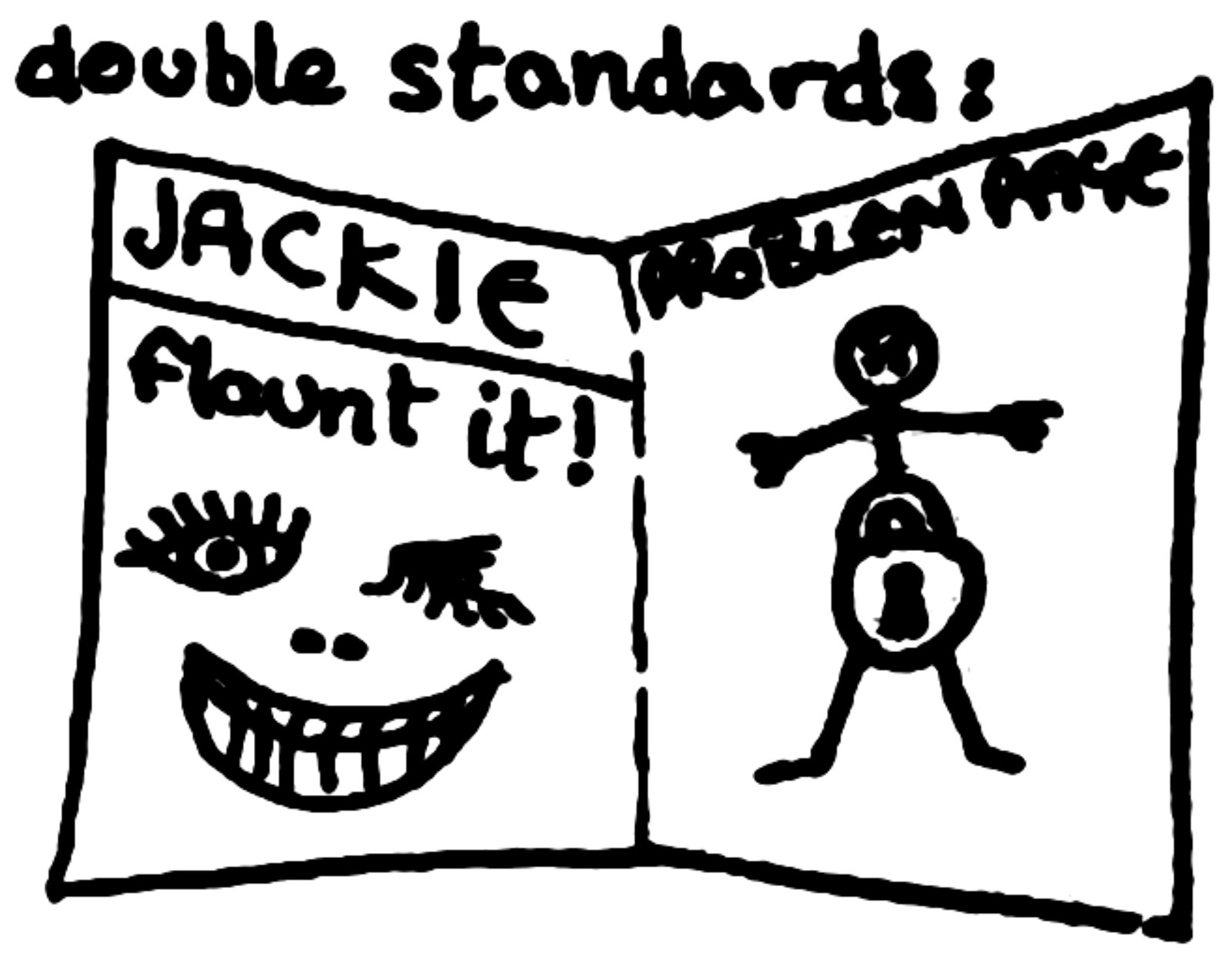

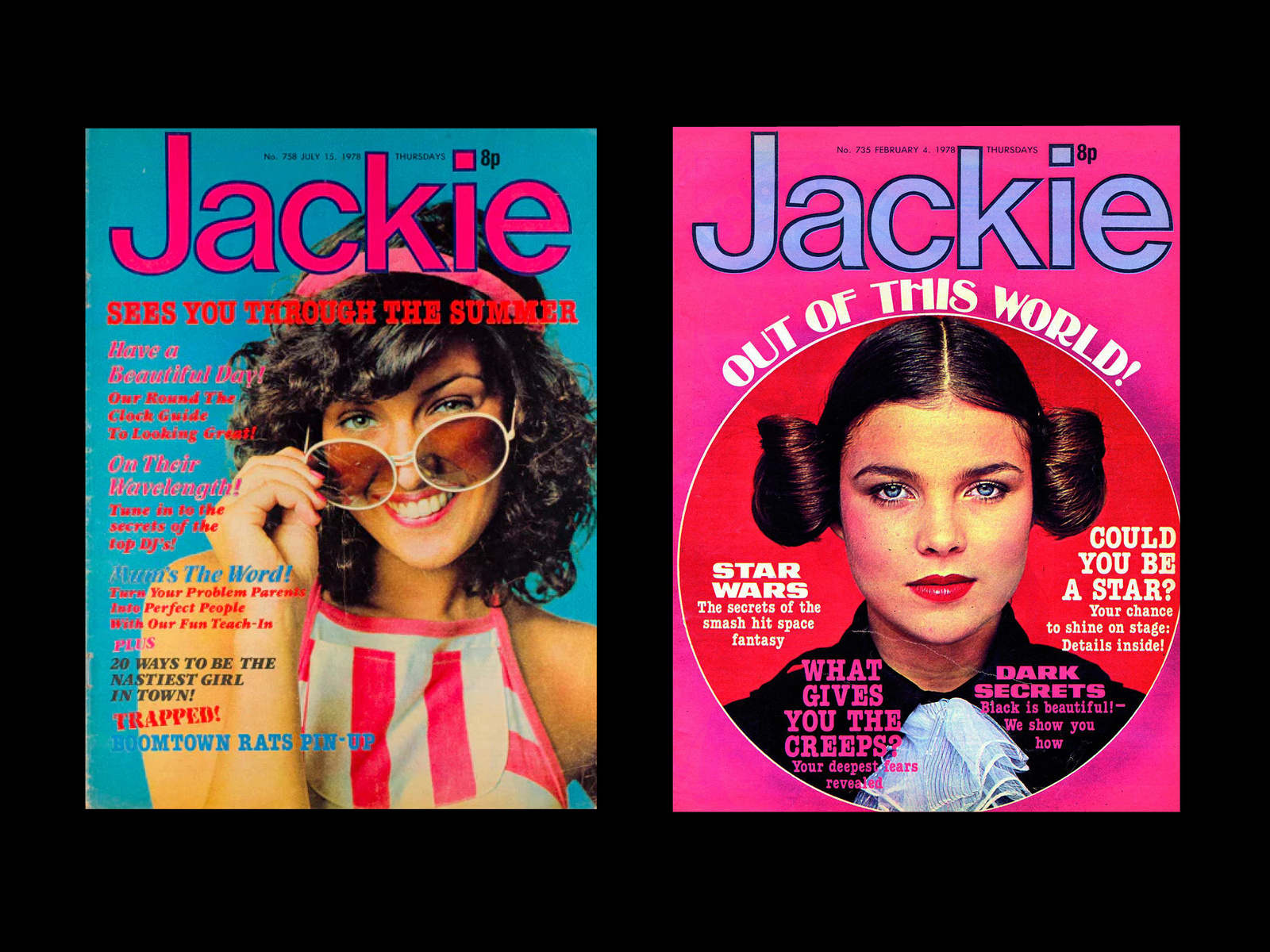

The first decision they made as a collective was an important statement on position; they wanted SP to be a “not-Jackie” magazine. At the time, Jackie was the best-loved teenage magazine in the UK, its content ranging from techniques to please men or capture/maintain their attention to beauty and style suggestions, short stories, and comics strips.

At the time, there was very little new literature coming out about feminism and, as SP put it, “feminist” had become a dirty word. The editorial team felt strongly that mainstream, female-focused printed material was boxing young women into a reality that wasn’t theirs, and reinforcing the stereotypical image of a woman with a perfect body and flawless manners. These young women felt there was more to uncover beyond the pettiness of general sexism and gender bias. A member of the first SP editorial group, who went by Mary Wollstonecraft, said (unfiltered) to the London Evening News in February of 1980: “We’re just starting to get the message across that a girl’s destiny is not to spend the rest of her life mending some bloke’s socks and moaning about her hair. Our new magazine will just be the beginning.”

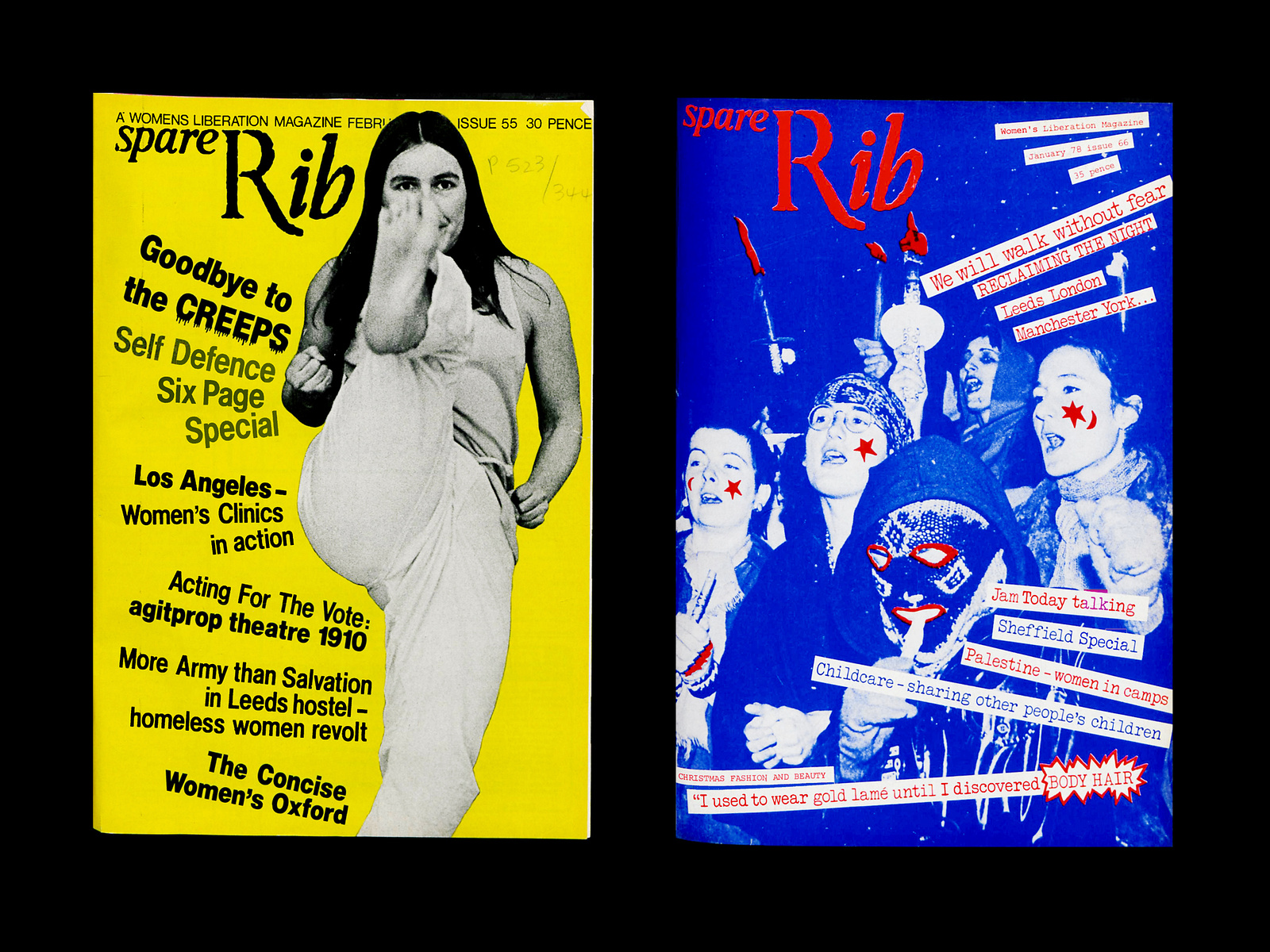

Covers of Spare Rib Magazine

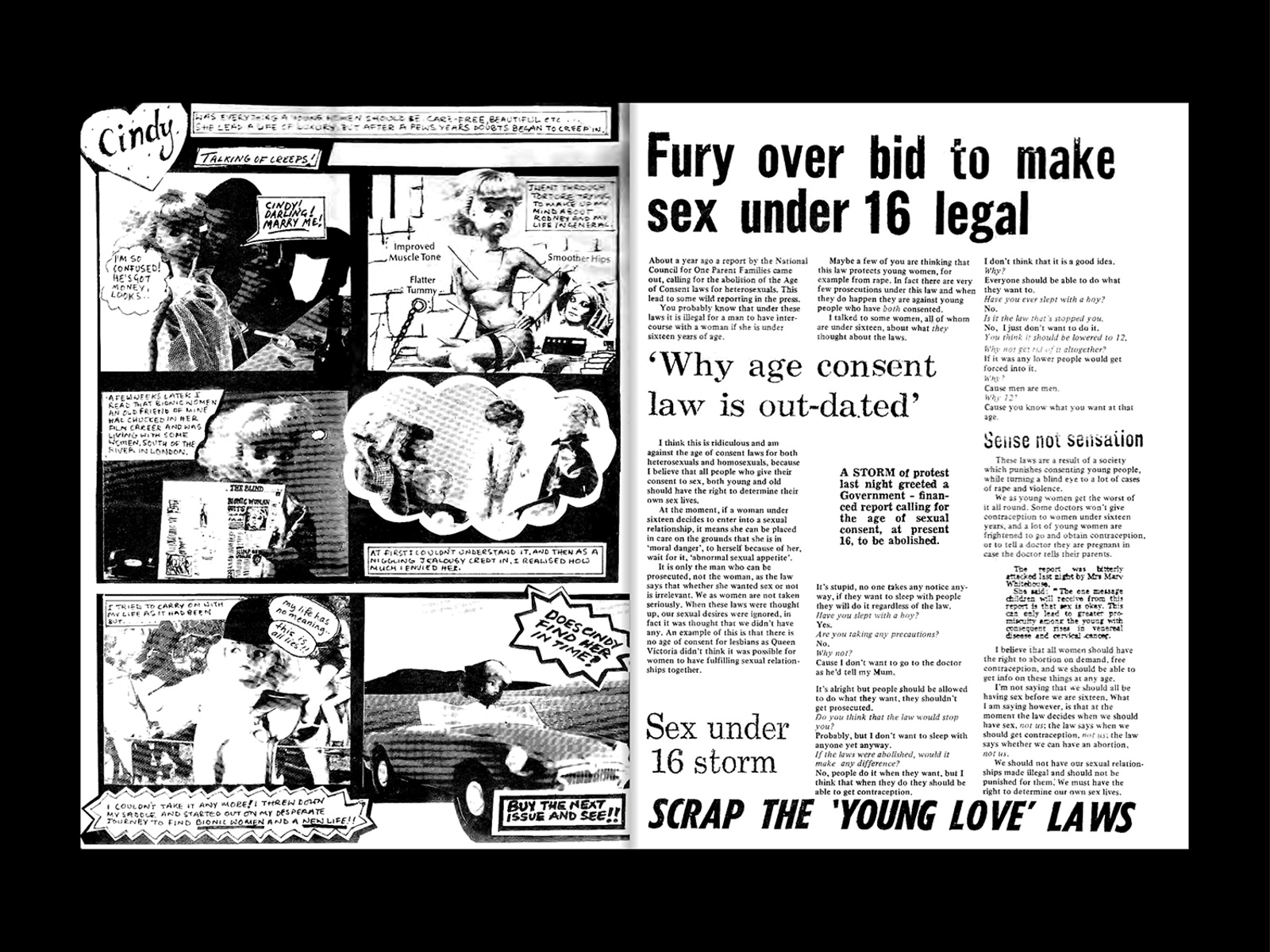

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 1

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 1

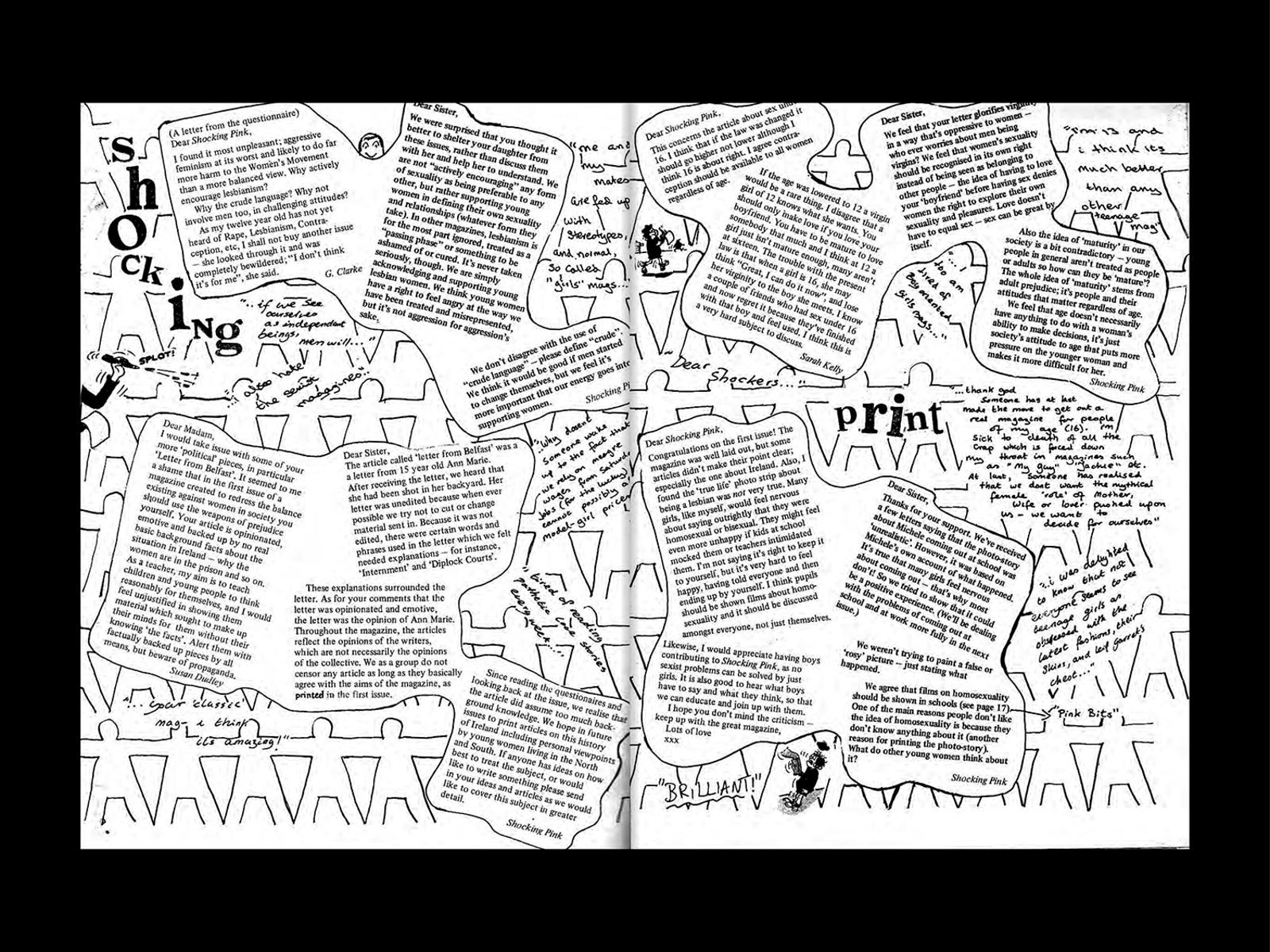

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 2

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 4

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 5

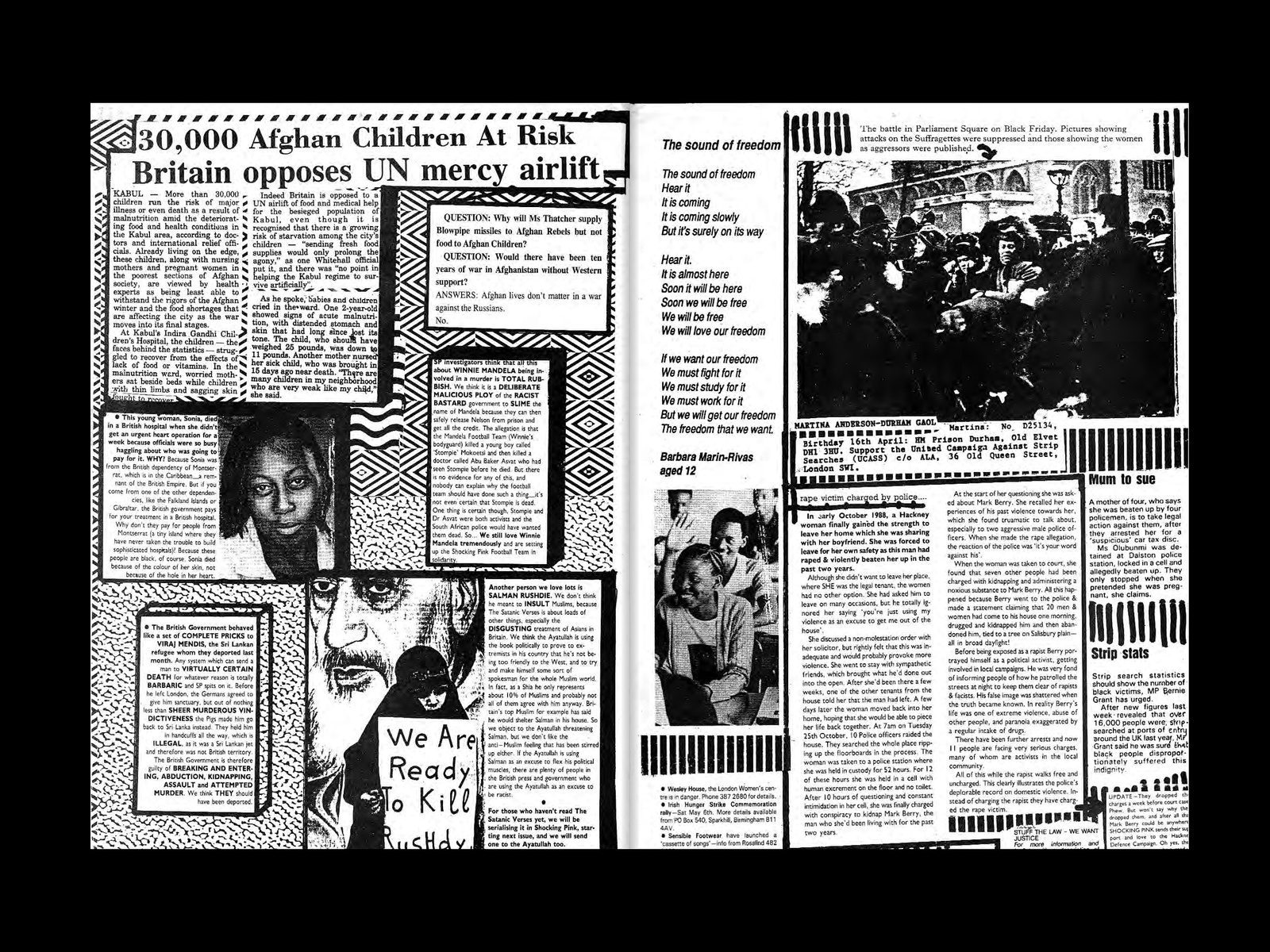

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 8

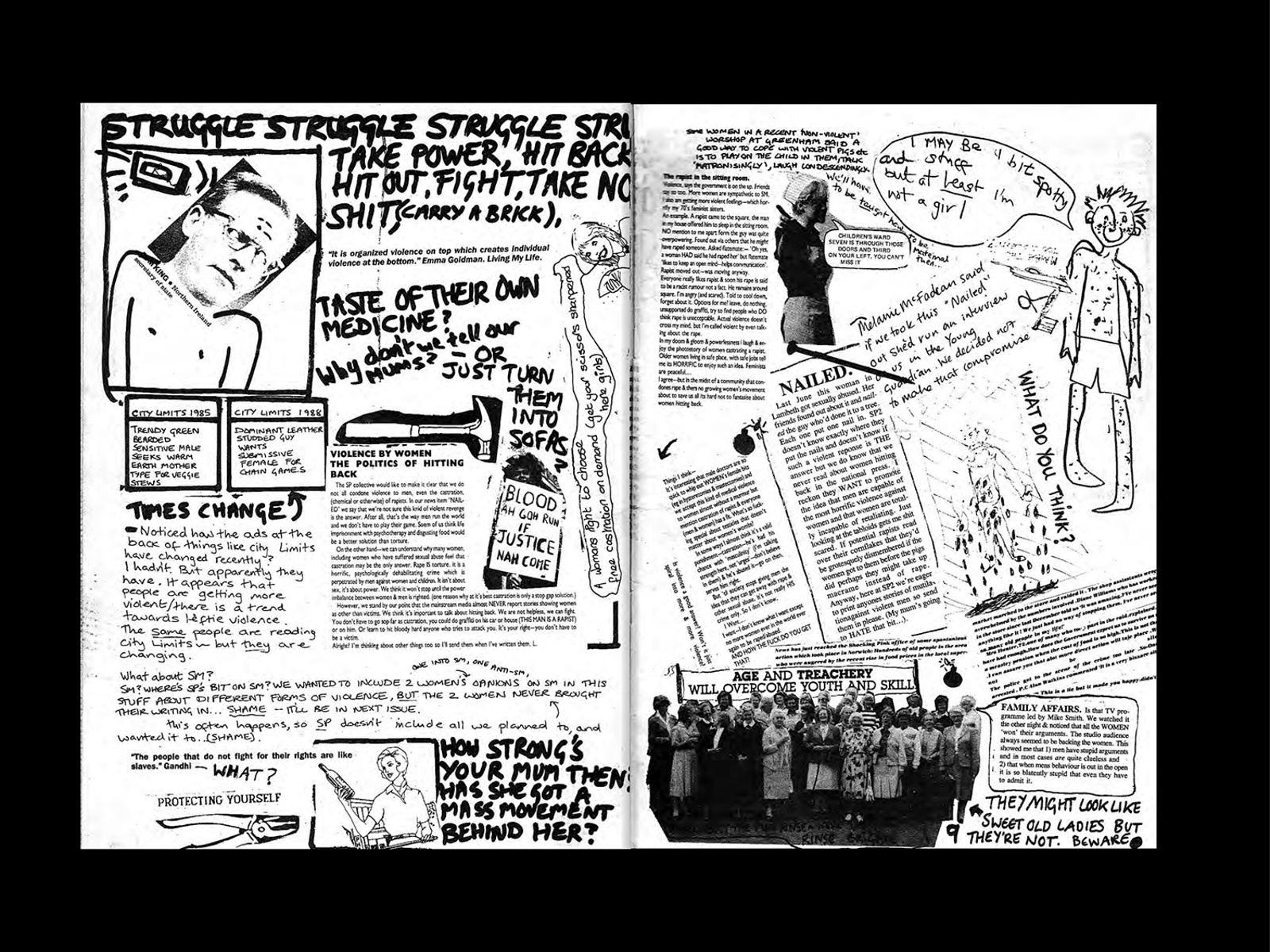

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 11

Spread from Shocking Pink Issue 12

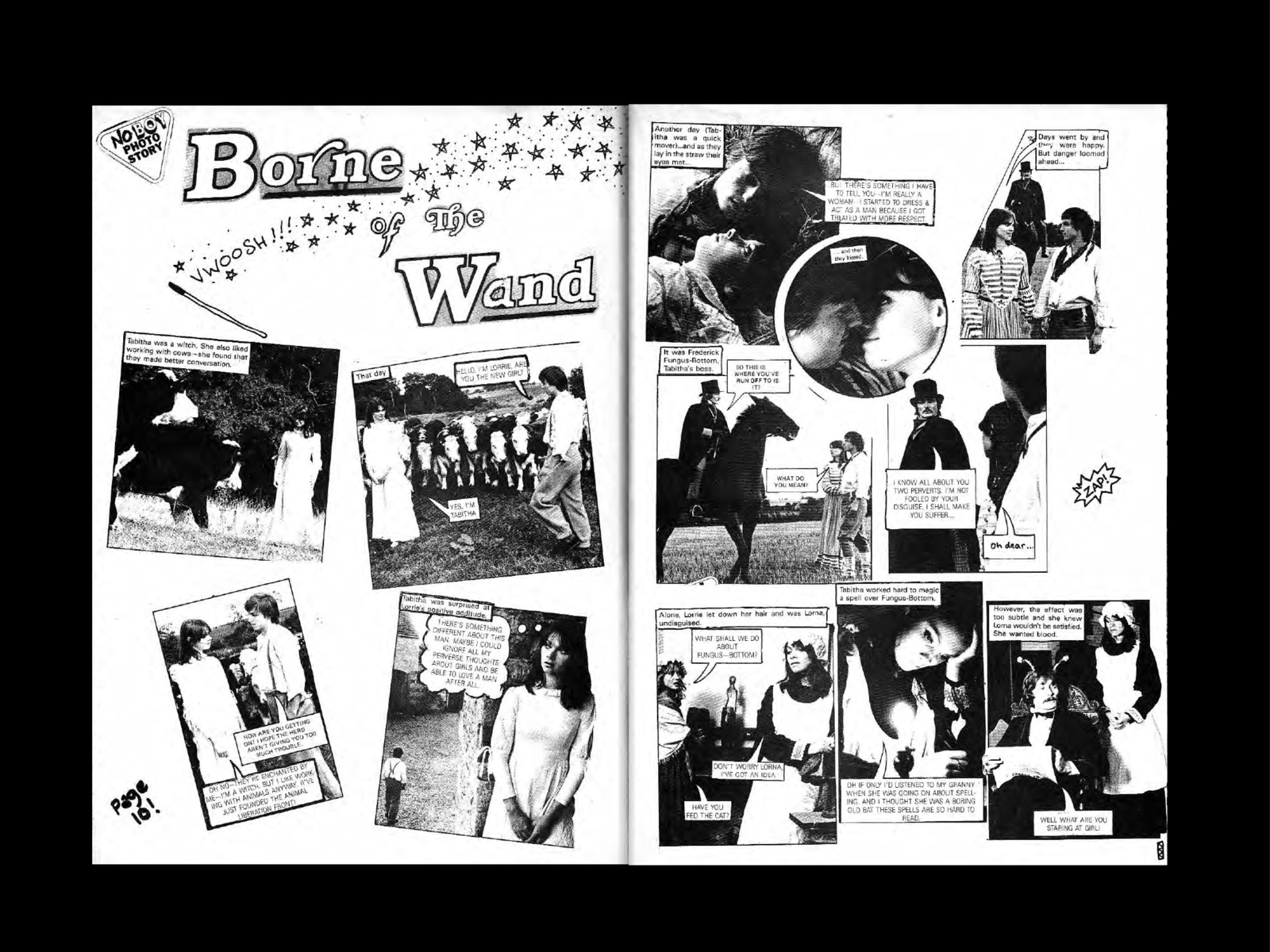

The name Shocking Pink — suggested by Lisa Bahaire and approved collectively — was meant to subvert the color pink as representative of conventional femininity. In direct opposition to the typical glossy girl-magazine voice, the group wanted to “shock” the female reader with the true face of the struggle. “We need a magazine that looks at other things, too: issues that really affect our lives, like nuclear power and weapons, violence against women, racism, contraception, abortion, sexuality, all aspects of women’s rights, books, opportunities in education and at work,” read the minutes of a meeting in 1980. Their explosive first issue showed how uncompromising the collective was in their desire to expose societal sexism and reject the status quo. Alongside articles about sexuality, they also ran a photo story about gay bullying at school, which documented a first-hand experience of one of the members of the team.

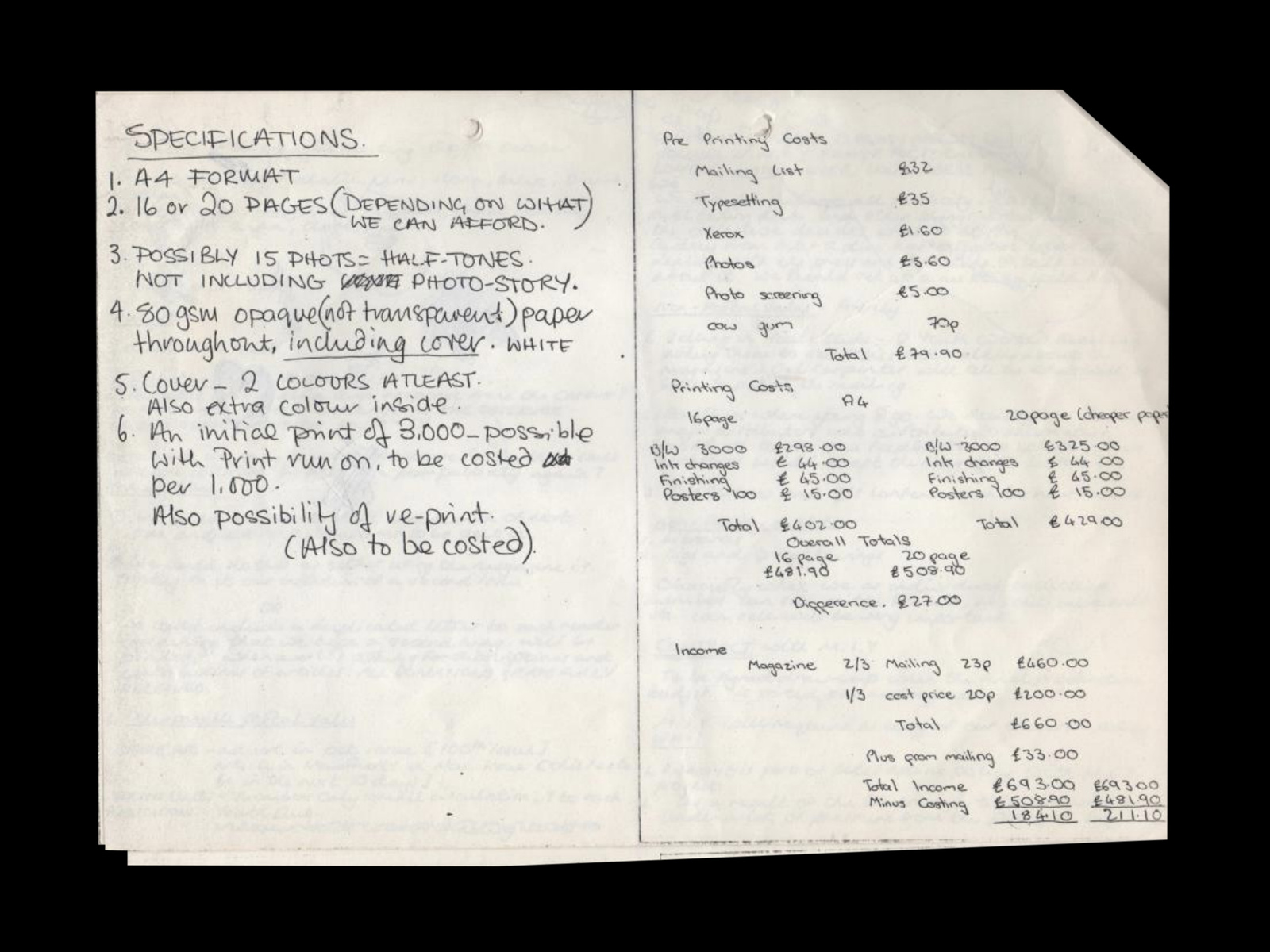

Weekly meetings were a fundamental part of their creative process. Many of their conversations were recorded — these were at times casual and explorative, other times strictly magazine-focused — to extract topics and themes for every issue. The printing was done with a small budget collected through fundraising, small grants, and donations. Depending on finances, the issues ranged through the years between 16 to 40 pages, sitting somewhere between a magazine and a zine in its later releases. At first, SP was priced at only 20p and distributed by mail, or handed out during (non-political) gigs, feminist and LGBTQ+ events and parties.

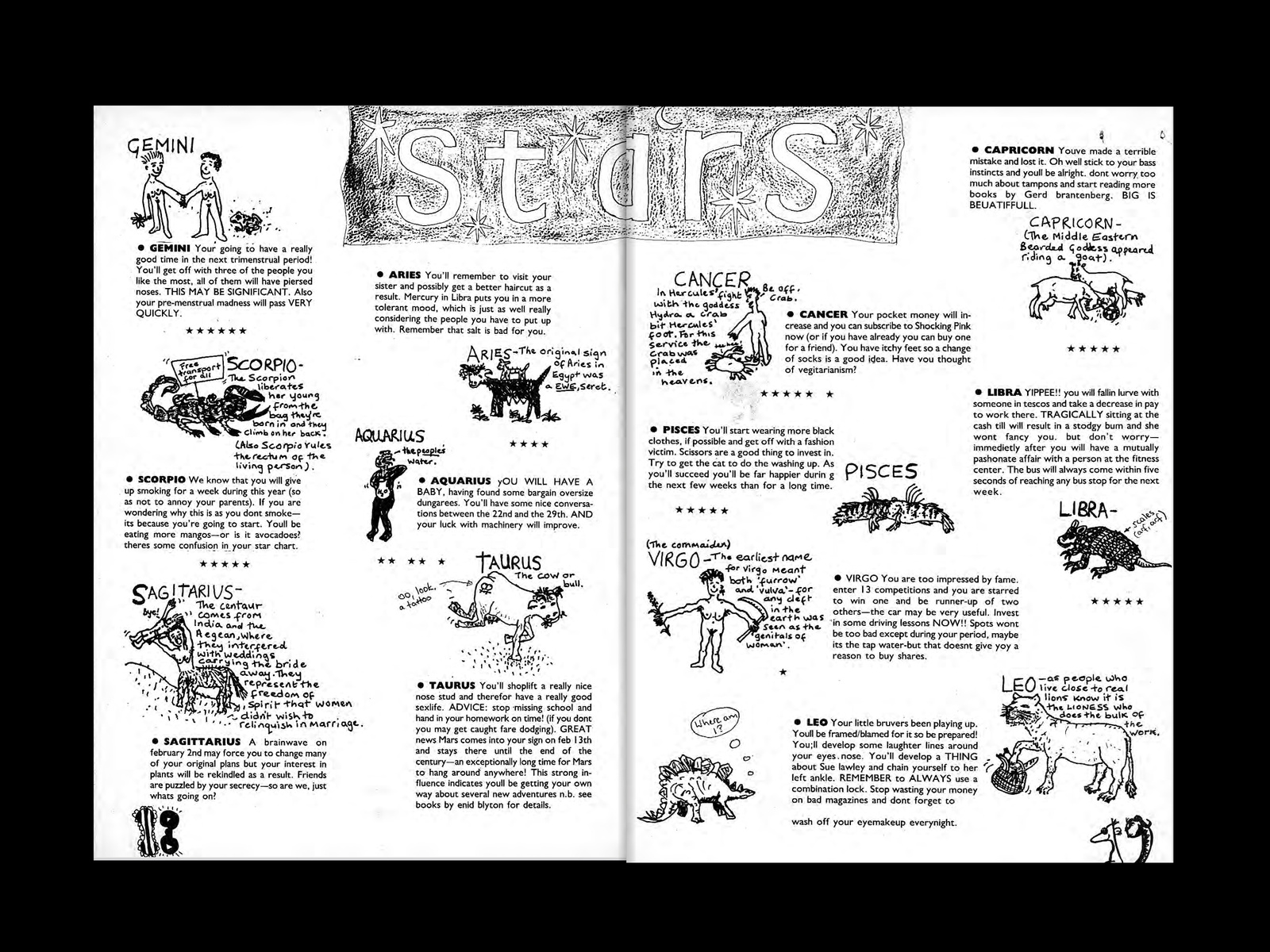

The magazine developed through the years a cut-and-paste, DIY aesthetic that was gaining popularity with the punk movement a few years earlier, but had no allegiance to any distinct style. With no specific design-related skills, SP’s collective developed a personal aesthetic whose only constant was that it was ever-changing: the issues weren’t always clearly numbered, nor did they publish them at a steady cadence. The format remained the same — A4 for easiness of printing — but the paper, the pagination, the structure, and title evolved issue to issue. Even the shade of “shocking pink” changed multiple times. As the members of the first collective recall, their aim was to make a magazine, not a fanzine, one which could sit, tongue in cheek, alongside the mainstream periodicals; the photostories, the charts and quizzes, the newsletter section — these where all elements they wanted to borrow from Blue Jeans and Jackie’s visual language. Their aim was to appropriate that glossy look and feel, but as a self-funded enterprise, the level of production needed wasn’t affordable, at least at the start.

Spare Rib offered substantial assistance with the first issue, helping with the fundraising, but most importantly sharing their expertise about things like collating layouts or working with a printer, where to buy the layout boards, and who to call to do the typesetting. During their meetings, the collective would start by placing the cut up type-set articles, Letraset, handwritten pieces, and photography on large layout boards.They assembled everything with economy of space in mind; the typesetted text was always the first content to be placed, followed by images, titles, and ads. Once everything was glued to the layout sheets, the members who were good at illustration would draw doodles to fill the gaps. Just as Shocking Pink was part of the lineage of Spare Rib, it would go on to inspire the Riot Grrrl zines with its fusion of political talk, social concern, school-club sections, and ironic doodles.The illustrations were always responding to the theme of the issue or particular articles, sometimes borrowing from members’ daily lives and real situations and featuring them making the same comments or remarks they made so many times around the layout table.

Covers of Jackie Magazine

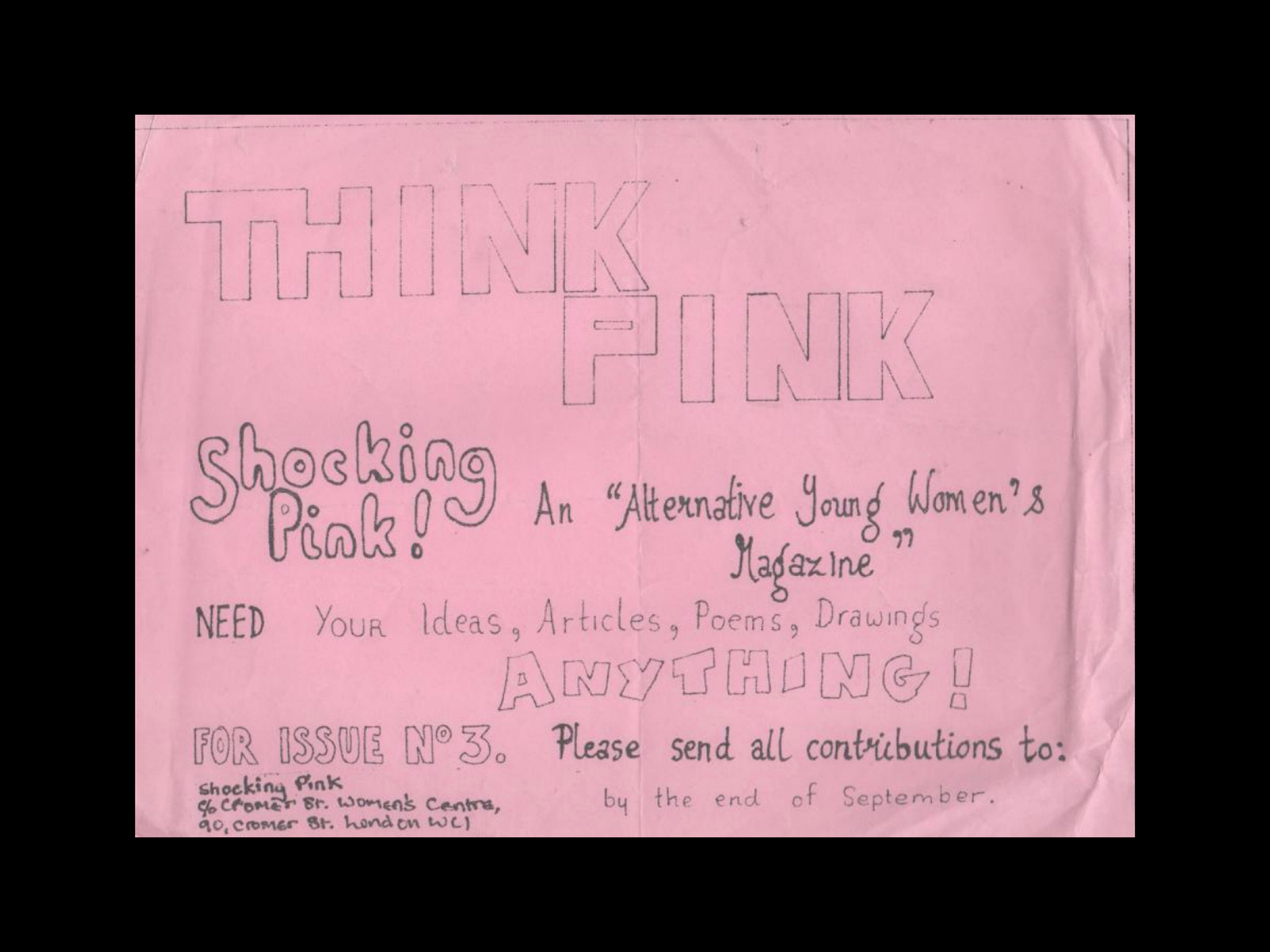

Shocking Pink flyer calling for contributors for Issue 3

Ad for Shocking Pink, NME (c. 1983)

Article about Shocking Pink in The Observer Magazine (1980)

Shocking Pink ad for badges in Spare Rib (1981)

Shocking Pink Badge

Shocking Pink, meeting minutes (1980)

In the 1980s, England was facing social, political, and economic turmoil; in most underground circles, the status quo, the future, and tradition were oft-discussed topics. On May 4, 1979, Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister, a position she held until late 1990, when she was ousted by her own conservative party. During Thatcher’s years, inflation peaked and unemployment was high, but there was also the economic boom of the “Yuppie-years,” led by an acceleration of consumerism and the stock market boom. At home, Thatcher’s term saw mass privatization, hooliganism, austerity, the post-punk culture, and the UK miners’ strike, to name a few. Abroad, the collapse of the USSR symbolized by the fall of the Berlin Wall put an end to the Cold War, and marked the rise of neoliberalism.

SP’s collective were coming of age during that time of fast global evolution, and they wanted the massive cultural change they were experiencing to be part of the magazine. Because their attitude was to be as young and contemporary as possible, SP moved organically through three different editorial teams and was produced in three discrete moments: 1980-82, 1987-89, and 1989-92. The core members of the first team left after just 3 issues; they felt they weren’t young women anymore and that a new group could better continue with a renewed urgency and freshness.

From first the collective to the second, SP changed significantly. The new editors felt that they needed to radicalize — partly because the conversations around feminism had gone stagnant, and partly because of the sexism they encountered in even the most left wing circles, as well as the political situation they saw unfolding around them. In May 1988, the government passed Clause 28 to stop local authorities from “intentionally promoting homosexuality,” causing many organizations and student support groups to close. The AIDS crisis was also underway, which led to ostracization of the queer community and mass hysteria. SP, meanwhile, continued with their counter-cultural action, publishing a piece on rapist castration and running imagery explaining the reproductive organs, unafraid of the ramping up of legal cases against indecency. While the first era of SP published mostly about school life and new ways of being a young feminist, this change of command made the magazine more action-focused, politicized, and anti-establishment, and it started gathering an important lesbian post-punk following.

As the second collective started to move on toward the end of the decade, Katy Watson took over as editor, after having previous experience with feminist presses. As Watson mentioned in a 2008 interview, Shocking Pink opted for a non-edited approach during the last years it was in operation. The editors still selected the articles to run, but they didn’t alter the content. Their work was primarily in sequencing, designing, and fitting together the whole.

Iranian schoolgirls removing their hijabs and giving Ayatollah Khamenei and Ayatollah Khomeini the middle finger

Today in the West, it is said by some that women have achieved freedom and equality. They run mega-corporations and entire countries — haven’t they gotten their seat at the table? This has, on the one hand, led people to think of feminism as a topic for academic research and theory, rather than something that affects the everyday, something to practice. This could be why there seems to be a certain anxiety or uncertainty around talking about feminism from people who don’t view themselves as experts. On the other hand, it could also be said that the popularity of certain feminist beliefs have reached the level of cliche, as feminist ideas are chewed up by mainstream culture and digested as catchy marketing copy. Because of this, the statements feminists make and the opinions we share are perceived by some as naive, retrograde, or even lamentous, as if to say, can’t you just be content with all of the cultural “progress” that women have already made in society?

The creators of Shocking Pink were young, but they were not afraid to speak up, even at a time when mainstream media was proclaiming women had everything they wanted. They held strong opinions and led frank, open dialogue through publishing. An incredible willpower comes through in all of SP’s pages. Looking back on the issues now, the writing is remarkable in many ways. It leaves behind a comprehensive map of what it meant to be young and a woman — queer or straight — in the UK during the 1980s. SP’s young editors disagreed with much of the legacy left to them from the feminist movements of previous decades, and they refused to quietly accept what older generations had laid out for them. They also rejected a social system where the woman’s body and mind are stereotyped and commodified. Shocking Pink filled an important gap at the time it was published, becoming a reference point for minorities and marginalized groups within the wider feminism movement. An early letter from a subscriber published in the magazine characterizes Shocking Pink as “marvelous, amusing, tacky, and offensive” — exactly what is necessary to shake the status quo.

This piece was selected as a winner from the 2022 Source Type Editorial Open Call.