Transnistria, Stamps & Sovereignty

According to the United Nations, there are 193 countries on earth. But what exactly makes a state? A permanent population, a defined territory, a government? In the international system, the determinant factor seems to be its formal recognition by other states. In reality, however, there are many places that don’t officially exist. De jure, they may be legally considered part of another country, but de facto, they operate as an independent entity, alive in the minds of a group of people attempting to claim their autonomy.

If you look closely at the map of the world, you’ll find a number of unrecognized states, micronations, and curious border zones. Borders that appear to be represented by clearly defined lines are in reality highly contested and blurred. Often, the history of these territories is complex, and their geopolitics play a large role in determining their future, and the consequences for the people who live there. As a graphic designer, I find it fascinating how objects such as stamps, flags, or maps reflect and reinforce identity politics and struggles for independence. All of these items are highly politicized: A stamp can be a mini-manifesto, a map formalizes borders, and paper money issued makes a country more legit. For many years, I’ve been collecting these types of objects and sharing them on the website defactoborders.org, an initiative by journalist Jorie Horsthuis and myself, where we also (re)publish stories from these places to show the effect global developments have on people’s daily lives.

For unrecognized states these items play an important role in developing national identity, often showing new customs and traditions, and in doing so creating a common ground. It’s no surprise that they commonly commemorate the fallen heroes of battles for independence, or that the date of issue coincides with the start of a revolution. Objects from border conflicts serve the purpose of reasserting power—either considered proud emblems of identity or blatant vehicles of propaganda, depending on which side of the conflict you are viewing them from.

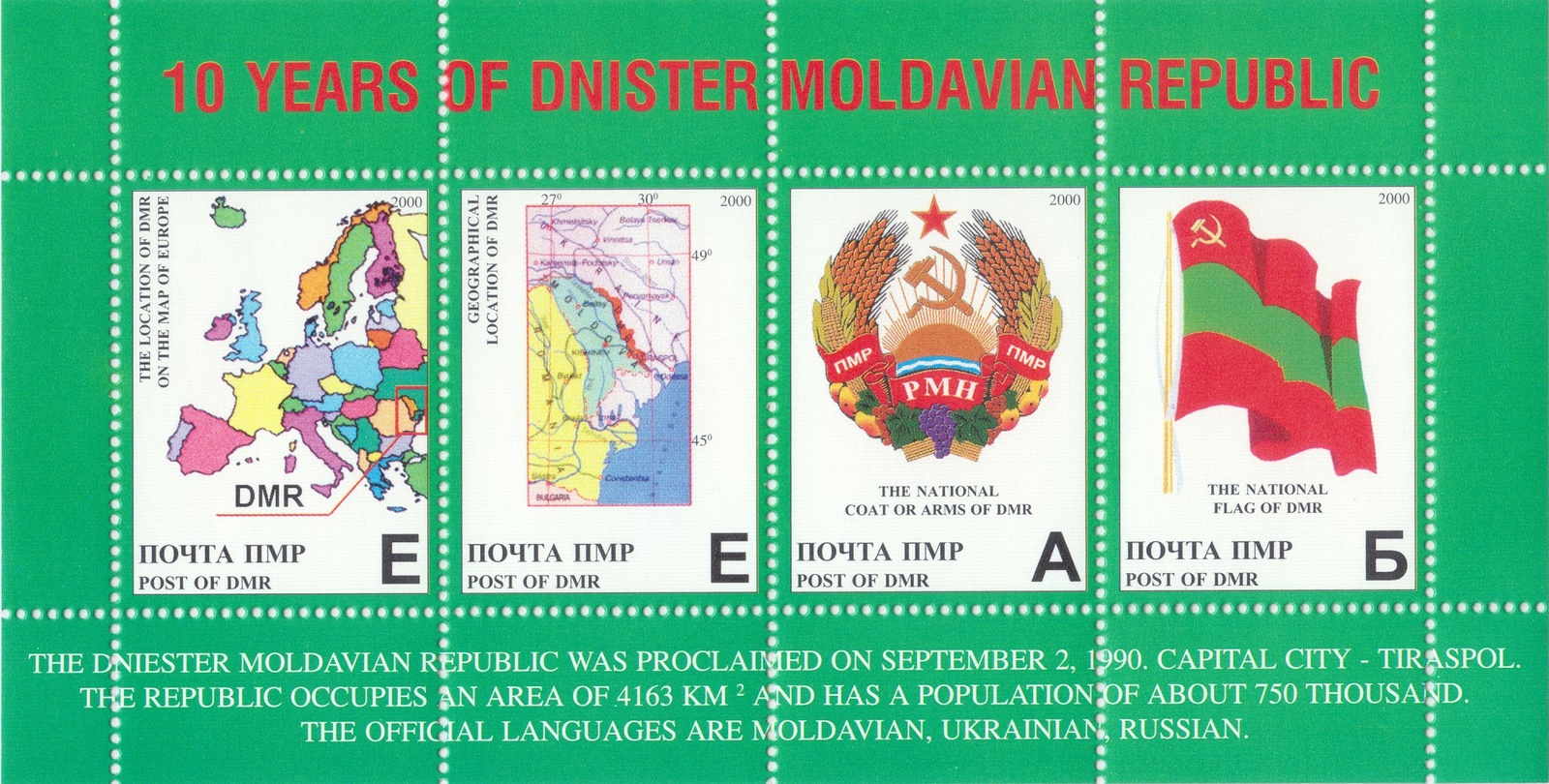

Stamp set from Transnistria; “10 Years of Dnister Moldavian Republic. Maps of Europe and PMR, Coat of Arms and Flag.” Year of issue: 2000, printrun: 5000, 141 x 72 mm.

One of the first stamps I ever bought was from Transnistria, a small strip of land located between the Dniester River and the east Moldovan border with Ukraine. I purchase most of my collection online. For me, it’s a way to travel to these places. Stamp collecting is not a very sexy hobby but it has a very lively and active online community, populated by mostly older men with a keen interest in World War I. After the Soviet Union fell, Transnistria declared its independence from the Moldavian SSR, which in turn declared its independence from the USSR in 1991 and became Moldova. The two neighboring states ended up at war, which lasted around two years and resulted in a ceasefire that continues to this day. Transnistria has only been recognized as a sovereign entity by the also unrecognized states of South Ossetia, Abkhazia, and Nagorno-Karabakh. The United Nations still legally considers it to be a part of the Republic of Moldova, and Russia, which still has a military presence in the country, doesn’t recognize Transnistria due to complex geopolitical relations in the region.

This stamp set was issued ten years after Transnistria’s declaration of independence, and though the text is in English, they aren’t valid for sending international mail. The stamps are loaded with Soviet symbolism, a nod to the fact that Russians gave Transnistria military support during the war with Moldova. The flag and the coat of arms both refer to the state emblem of the former Soviet Union, showing the most famous Russian symbol of proletarian solidarity: the hammer and sickle, representing the union between the working class and farmers.

State emblem of the Soviet Union carrying the motto: “Workers of the world Unite.” July 6, 1923.

But for me, the two stamps on the left were what really piqued my interest. They illustrate how design can be used to put a country, quite literally, on the map. Maps on stamps assert territorial aspirations over a contested place: Simply by showing your position on a small official seal, the claim becomes legitimized and affirmed. This can be done in a number of ways, one of which is to annex the territory on the map, and another is to show your nation in the context of a larger community. Here, the stamp on the right reaffirms the strategic position that Transnistria holds between the East and West. Labeled “Geographical location of DMR,” the stamp shows a little red strip wedged between Ukraine and Moldova locating the Dnister Moldavian Republic, with the letters “DMR” crammed into the slender spot. As is typical for some unrecognized countries, this one is known by many names: Transnistria, or Transdniestria; in English, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic; or as it is here, Dnister Moldavian Republic (DMR). All names refer to the Romanian everyday name of the region: Transnistria, which means “Beyond the River Dniester.”

A close-up view of the stamp set from Transnistria, showing the two stamps on the left.

Zooming out, the left stamp locates Transnistria on a map of Europe, positioning the country on the international stage, and expressing a clear desire for recognition within the European arena. While it does serve as a buffer between Russia and Europe, what is most striking is that Transnistria is so small: it disappears on this scale, almost falling off of the map. A red square represents the area, but the country itself can’t be seen—an unintentionally symbolic gesture.

In this column I will be sharing more stories about these curious places through various ephemera—3D puzzles, unification flags, composite money, battle figurines, nautical maps, posters from Cuba, and a mango mousse—all things used to build upon the idea that identity can be legitimized through design. Among other locales, I’ll be reporting from outer space, a unified Korea, and from an exclave in Africa.